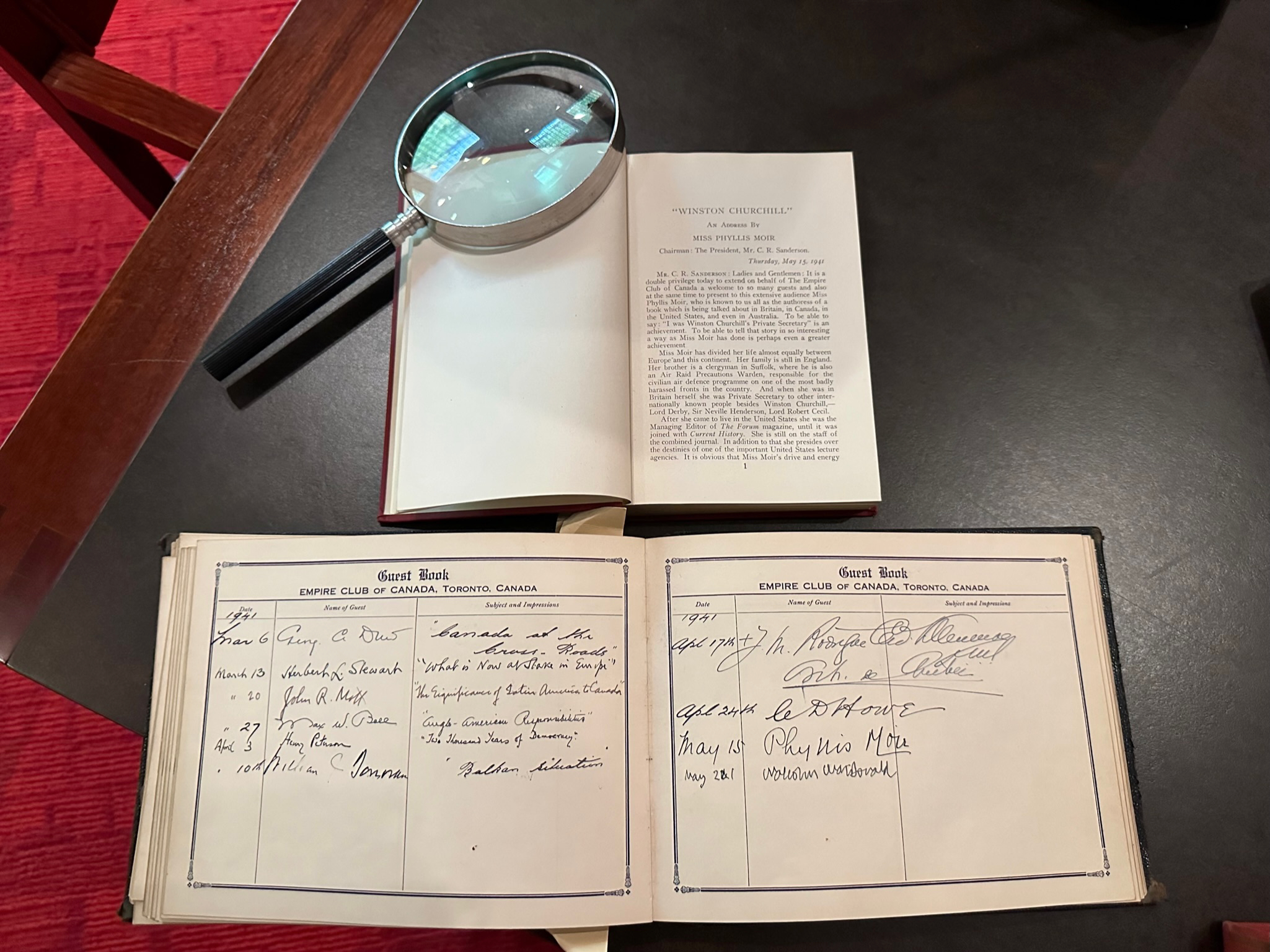

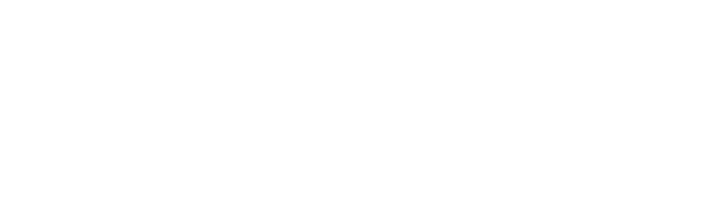

WINSTON CHURCHILL AN ADDRESS BY MISS PHYLLIS MOIRChairman: The President, Mr. C. R. Sanderson.Thursday, May 15, 1941

MR. C. R. SANDERSON: Ladies and Gentlemen: It is a double privilege today to extend on behalf of The Empire Club of Canada a welcome to so many guests and also at the same time to present to this extensive audience Miss Phyllis Moir, who is known to us all as the authoress of a hook which is being talked about in Britain, in Canada, in the United States, and even in Australia. To be able to say: “I was Winston Churchill’s Private Secretary” is an achievement. To be able to tell that story in so interesting a way as Miss Moir has done is perhaps even a greater achievement

Miss Moir has divided her life almost equally between Europe and this continent. Her family is still in England. Her brother is a clergyman in Suffolk, where he is also an Air Raid Precautions Warden, responsible for the civilian air defence programme on one of the most badly harassed fronts in the country. And when she was in Britain herself she was Private Secretary to other internationally known people besides Winston Churchill, Lord Derby, Sir Neville Henderson, Lord Robert Cecil.

After she came to live in the United States she was the Managing Editor of The Forum magazine, until it was joined with Current History. She is still on the staff of the combined journal. In addition to that she presides over the destinies of one of the important United States lecture agencies. It is obvious that Miss Moir’s drive and energy are just as great today as when her talents were being applied to the affairs of Winston Churchill.

Ladies and Gentlemen: I have great pleasure in presenting to you Miss Phyllis Moir. (Applause.)

MISS PHYLLIS MOIR: Mr. Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen: Thank you very much indeed for this cordial welcome. This visit to Toronto brings back vivid recollections of the last time I was here. I came in the company of the Right Honourable Winston Churchill and his daughter, and we stayed in this hotel. As a man who is easily pleased with the best of everything, Mr. Churchill and his party took over the Royal Suite–every inch of it

We were nearing the end of an extensive lecture tour which had taken us across the United States and finally brought us here, where Mr. Churchill addressed an enormous gathering in the Maple Leaf Gardens.

It was here in Toronto an incident occurred that demonstrated the fighting quality in his make-up that we all admire, a quality that exults in meeting difficulties and mastering them.

Some of you here today may remember that in the middle of his speech at Maple Leaf Gardens, the amplifying system broke down. Mr. Churchill didn’t notice it until cries of “Louder, Louder,” began to echo from all parts of the enclosure. Now, here was a situation to unnerve many an experienced speaker. The thought of it makes me quail, but not Mr. Churchill. I can still see him advancing resolutely to the edge of the platform and raising his hands for quiet. Then he took the portable microphone which was attached to his lapel, held it aloft for everyone to see, and with a dramatic gesture, flung it to the floor. In a loud resonant voice he thundered, “Now that we have exhausted the resources of science we shall fall back upon Mother Nature and do our best.” Then, just as though nothing had happened, he went on with his speech and held his audience spellbound to the end. I remember they gave him a great ovation–cries of “Good Old Winnie! You’ve done it again! Nothing downs you!” When an American publisher asked me to write a book about Winston Churchill the man-not the statesmanfor the statesman is his own best biographer-I was faced with the problem of how to make this incredibly gifted man credible to the reader. We all know close contact with the great is generally disappointing. No so with Mr. Churchill. The more closely and carefully you observe him the more his stature grows.

I think prodigious is the word that best describes Winston Churchill the man-artist, orator, soldier, journalist, proud father and devoted husband, a connoisseur of food and wine and beauty, a passionate lover of life, of its great moments and its small pleasures.

It was this side, the human side of Churchill,that I saw as his secretary throughout the lecture tour. There were five of us–Mr. Churchill, his daughter Diana, Louis J. Allier his lecture-manager, Sergeant Thompson from Scotland Yard, who is still with him by the way, and myself. We travelled together, visiting and sight-seeing together for some months.

Under such conditions, of course, one gets to know a person very well, especially a man like Winston Churchill, who is always completely himself.

The thing that strikes everyone who meets him for the first time is his overwhelming personality. It seems to fill any room he is in and to overflow it on all sides. I remember a prominent American impressario, a man who for twenty years had been introducing celebrities to the public, came away from his first meeting with Churchill in a daze.

“All I could consciously think of was how in the world I could get out of the man’s way”, he afterward confessed to me rather ruefully.

Mr. Churchill’s personality is an army with banners, and the banners are many and different. But one thing they have in common: all are patterned on the heroic scale. In his character there is no twilight, no smallness, no petty compromise. His talents are the product of the most extraordinary combination of brains and breeding, hard work and good fortune, self-conscious and unbounded patriotism, that have ever been assembled under one chimney pot hat.

One of his former secretaries, who is now a well known novelist, has described the experience of working for Mr. Churchill as “an exercise in exhaustion”. I wouldn’t go quite as far as that but I admit I found it fairly strenuous.

That 100-horsepower Churchillian mind can generate more ideas in a day than some people have in a lifetime. In 1914, when he was First Lord of the Admiralty, and the world still had an uneasy peace, Churchill used to amuse himself’ by writing a series of memoranda to his fellow Cabinet Ministers. He called them “Imaginative exercises, designed to disturb complacency.” All his life he has taken keen delight in disturbing the complacent. It is no wonder that a few years ago the London Economist called him “an uncomfortable person to have around”. Today, Britain’s Prime Minister has six secretaries, I believe. But I still think it isn’t enough. He could keep a round dozen busy all the time. Mr. Churchill’s idea of relaxing from politics and speech-making is merely to indulge in different forms of activity, such as brick-laying, painting, or writing. But I have always thought that good conversation is probably his favourite hobby.

They tell a story around New York of Winston Churchill’s meeting with Mark Twain, when the young Englishman came to the United States for his first lecture tour in 1900. Even then Churchill was known as a passionate conversationalist and so, of course, was Twain. A friend who saw the two men going off together after dinner took a wager that Twain would succeed in doing most of the talking. When they emerged some time later, somebody asked Twain how he had made out. “Well,” said Twain, laconically, “I had a good smoke”.

During my association with Mr. Churchill I came early to the conclusion that he is always at his best when his back is to the wall. It is for this reason that he seems to the whole English-speaking world, including the United States, to have become the spokesman for the democratic way of life. As Dorothy Thompson has so aptly said “When Churchill speaks there are no neutral hearts”.

Of course Mr. Churchill has always been an eloquent speaker. Today when his voice reaches us over the air it is not merely the magic of his words that moves us. It is the compelling sense that this man is in himself the pledge that “liberty shall not perish from the earth”, that the things of the spirit are unconquerable.

Only two months after Churchill had shouldered Chamberlain’s legacy of defeat, a young British soldier wrote these words to a friend in America: “England, at last, is a real nation, really led; a handful of brave, resolute men, and one genuinely great man at the top. The whole rhythm of our national life has changed. We think virilely; we hold ourselves as men who know what we must face and what we must do. We are alive again”.

How did Mr. Churchill, in so short a time, succeed in dispelling the doubts, the fears, the hesitations, that had plagued England throughout the first winter of war? How did he infuse in his countrymen the spirit that is now the wonder of the democratic world? He did it, I think, by his own unquestioning faith in the greatness of ordinary men and women. It has always been his belief that mankind can rise to any ordeal, however terrible, can endure untold suffering, even death, for the sake of a good cause. After he himself had once been at death’s door, he wrote these very revealing words: “Nature is merciful and does not try her children, man or beast, beyond their compass. Live dangerously, dread naught, and all will be well”.

It is this resolute will in the face of danger that has so captured the admiration and affection of the American public. The American estimate of a man is apt to be simple, founded on his ability to take defeat in his stride, to triumph over adversity, to win through to victory when the chances of victory seem negligible. There would have been far less sympathy for England among the people of the United States had things gone well for England from the outset of the war. From the moment that Great Britain became an island fortress with every man, woman, and child in the front line, the tide of American feeling turned strongly toward England.

What happened? Volunteer organizations in aid of Britain appeared everywhere. Even the foreign policy of the country was transformed by the passage of the Lend-Lease Bill. Today most people in the United States believe that aid to Britain must be made effective. What still divides them, however, is the question of the most expedient means of insuring this. From being merely the agitated fringe of the crisis the United States has become the centre of the crisis.

You know, it is really astonishing to come from the strife of a country at peace to the peace of a country at war. Here in Canada your decisions are taken, your course is clear, and you have peace within yourselves. But in the United States we are uncertain and confused. We stand on the brink of momentous decisions. We know that they must be made, and that, whatever they may be, the consequences will affect the lives of all Americans for long years to come. That is why today there is raging in the United States a debate more tense, more violent, and more widespread, than any since the Civil War.

I have been told by Canadian friends that echoes of that debate are heard in Canada but the causes are not understood. Let me say very humbly that I am no expert in these matters. I speak only as one born in England, but a resident of the United States for some twenty years. The American people know they are confronted with a life and death issue-whether to continue the present policy of aid to Britain, short of war, or whether to adopt more drastic measures regardless of the consequences. There is no question of ceasing aid to Britain. The crucial question is: What risks are we willing to adopt in giving that aid?

Now, in this debate there are many varying shades of opinion, but there are in general two major divisions. There are those who, led by members of Mr. Roosevelt’s entourage, notably Mr. Hopkins, Mr. Bullitt, Secretary of War Stimson, and Secretary of Navy Knox, believe that the United States must now assume any risks required to secure an eventual British victory. The other group, as most Americans recognize, is a minority. This minority is not overwhelmingly important numerically, but it is very important vocally. It commands certain channels of communication and publicity, and it commands these largely because its leaders have a high publicity value. Colonel Lindbergh, one of the leaders of the “America First Committee”, is its most notorious spokesman. Many Americans regard him with sympathy because of his heroic exploit in flying the Atlantic, and also because of the tragic disaster in his personal life. This sympathy is what secures him a hearing with the public, but he is not heard because anybody assumes that he speaks with either knowledge or authority on foreign affairs. He has the prestige of a confused and slightly tarnished hero.

Senators Wheeler and Nye, and other less well-known isolationist Senators, are relics of a period in which American disillusion with European politics crystallized in a determination to stay out of foreign entanglements. The bitterness of the attack made by Colonel Lindbergh and Senator Wheeler on aid to Britain has, however, served one significantly useful purpose. It has given the majority something to shoot at. It has, in a sense, focussed and made articulate majority opinion.

Under the American democratic system a decision on a great issue is supposed to reflect not the opinion of the Administration but the actual wishes of a majority of the people. In this crisis, therefore, President Roosevelt is pursuing two courses simultaneously. Through the public utterances of members of his Cabinet he is furnishing such lead as he can for public opinion; but he is withholding his final decision so that the wishes of the people may phrase it for him.

Now you might think that Mr. Churchill, more profoundly aware of dire emergency than any other individual in the world at this time, would betray some im patience–for he is by nature an impatient person-with American indecision. The fact that he does not is probably due to his own personal experience. I do not think he has forgotten that for years he was a prophet in the wilderness, a minority of one against the complacency and inertia of British leadership and British opinion.

There is a tragic irony in the fact that only when Mr. Churchill’s prophecies of disaster had been proved true, was he called upon to lend his wisdom, his intellectual brilliance, and the force of his personality, to the counsels of His Majesty’s Government.

I was in London on the memorable 28th of September, 1938, when Mr. Churchill stood alone against the general desire for peace at all costs. The evening papers called him “an alarmist”, “a Tory Cassandra”, and lightly discarded his prophecies of disaster. Just before returning to the United States I visited Virginia Wolfe and her husband. They, too, were convinced that Munich was only a reprieve, a breathing space in which to prepare for the conflict ahead. We talked of the possibility of new leaders. Mrs. Wolfe reminded me that England’s greatest strength was her ability to produce a leader when one was needed.

Well, we all know England did produce a leader. Mr. Churchill was assigned the role he had so long waited for, but only when the whole stage threatened to collapse under him at any moment. Almost instantaneously he rallied the morale of the British people. To the world it looked like a miracle, but, knowing Mr. Churchill, I believe that he accomplished it by the power of his own belief in the ability of every man, woman, and child, to do what he expected of them. There is no such word as “impossible” in Mr. Churchill’s vocabulary. I know that from experience. When I worked with him I found myself blithely accomplishing seeming impossibilities which I would never otherwise have attempted.

Now, he has welded the whole British nation together -Duke’s son and cook’s son-in a bond of human solidarity before the’ common danger.

My mother, who lives in a town that is being very heavily bombed, wrote to me recently. She told me that they were not afraid of anything. She has several times been blown out of her bed but she still insists on going to it. She will have nothing to do with an air raid shelter–she is a very intrepid old lady–and she ended up with these words (and Mr. Sanderrson has asked me to tell them to you): “I trust in God and why should I be afraid?” (Applause.)

How far Mr. Churchill has infused the common people of England with his own resolute spirit of defiance must be clear to you if you have seen a picture that has been widely reproduced in the United States. It is a news picture of a little boy from London’s East End, Frederick Harrison, aged 6, standing feet squarely planted on the ruins of his home, his jaw set in a grim challenge, his arm protectively around his baby sister whom he has just dug out of the debris. To me that childish figure will always be a symbol of the indomitable spirit of Britain and its great leader.

June, 1940, was perhaps the grimmest month in England’s history. It is characteristic of Winston Churchill that danger should have wrung from him the most stirring and the most beautiful utterances of his career. It was characteristic of him to call the darkest hour in England’s history her “finest hour”. At the moment when the world assumed defeat to be imminent Britain’s Prime Minister asserted the power of a moral victory; a victory over fear, doubt, and recrimination. More than two thousand years ago a Greek poet voiced what Mr. Churchill in that dark hour achieved

“To stand, from fear set free, to breathe and wait, To hold a hand uplifted over hate”.

A few nights ago the Nazis bombed Westminster Abbey. It was impossible for any English-speaking person to read of the damage to that ancient shrine without a feeling of profound emotion. The Abbey belongs to all of us. It is much more than a physical symbol of our great past. It is the spiritual meeting place of the past with the present, a haven of refuge in time of trouble. I think of it as I saw it last, during the Munich crisis. Through its stately doors there came and went a silent stream of men and women. They came to kneel and pray for the peace that was denied them, or for strength to endure the ordeals that might be ahead.

By his attack on that symbol of much that is great and noble in English life, Hitler has kindled in our hearts a flame that will burn brightly long after the bombing of London has become a memory. I think that I speak f or you all when I say that, though Hitler may destroy every stick and stone of our great heritage, he cannot destroy the spirit that has made that heritage endure through the ages.

Two hundred years ago the English poet, Thomas Gray, author of the famous Elegy, wrote a little-known poem, in Latin, and it has just been translated. In it he prophesied another war and an ultimate victory, anticipating by a flight of imagination what has actully come to pass today

“The time will come, when thou shalt lift thine eyes, To watch a long-drawn battle in the skies,While aged peasants, too amazed for words, Stare at the flying fleets of wondrous birds.England, so long the mistress of the sea,Where winds and waves confess her sovereignty, Her ancient triumphs yet on high shall bear, And reign, the sovereign of the conquered air”.

I should like to leave this with you as an expression of what England knows, Canada believes, and the United States hopes for. (Applause.)

MR. C. R. SANDERSON: Miss Moir said that whatever Hitler does he will never destroy the spirit of Britain. In that we whole-heartedly believe. What Britain is prepared to face is shown by the arrangements which have been made all over the country for what are called Local Information Committees. A time is envisaged when communities may be completely isolated; when there may be no rail communication, no road communication, no mail, no telegraph, no telephone, no newspaper. And yet plans have been developed to get a bulletin of news to each one of these communities, where a Local Information Committee is prepared to distribute that information within its own area. England has already steeled herself to face physical destruction without moral disruption.

Miss Moir didn’t mention Winston Churchill’s lisp. I clearly remember the first time I heard him speak, almost thirty years ago. For about the opening two minutes of his address his lisp was a dominant feature; one’s mind almost tended to wander from what he was saying. Yet, after the first moment or so, so amazing was the man’s personality that one ceased to have the slightest consciousness of any lisp. Frankly, I do not know today whether he has a lisp or whether he hasn’t. If he has I do not hear it.

Miss Moir, we owe you a debt of gratitude for talking to us about a man who at this moment is guiding the destinies of the British Commonwealth of Nations. Be cause of the position which he holds I do not think our desire to know as much as we can of him is intrusive. Certainly, everything that we know, everything that we learn, increases not only our admiration of him but increases our confidence in him.

It is very often said that this is a man’s world. Men don’t say that-they know it isn’t so. It is as much a woman’s world as a man’s. One realizes that the limitless energy, the brilliance of mind, the very genius of men like ‘ Churchill, reach their enormous volume of achievement through the assistance of their secretaries. The secretaries of all great men are, so to speak, the essential amplifiers through which the voice of genius is able to speak to a wider world.

But I think, Miss Moir, that you share some of Mr. Churchill’s own gift of phraseology. Both what you have said today and the very charming language in which you have expressed it are things we shall remember. We thank you for coming to Toronto; we thank you for coming here and talking to us; and we thank you because you have said so many of the things we hoped you would say, from personal, intimate contact with perhaps the greatest figure in the world at this moment. Miss Moir, will you accept this expression of the appreciation of The Empire Club of Canada and of our visitors for your attendance with us today. (Applause.)