An Address by RUDOLF BING, C.B.E. General Manager, Metropolitan Opera, New York, N.Y.

Thursday, March 28th, 1957

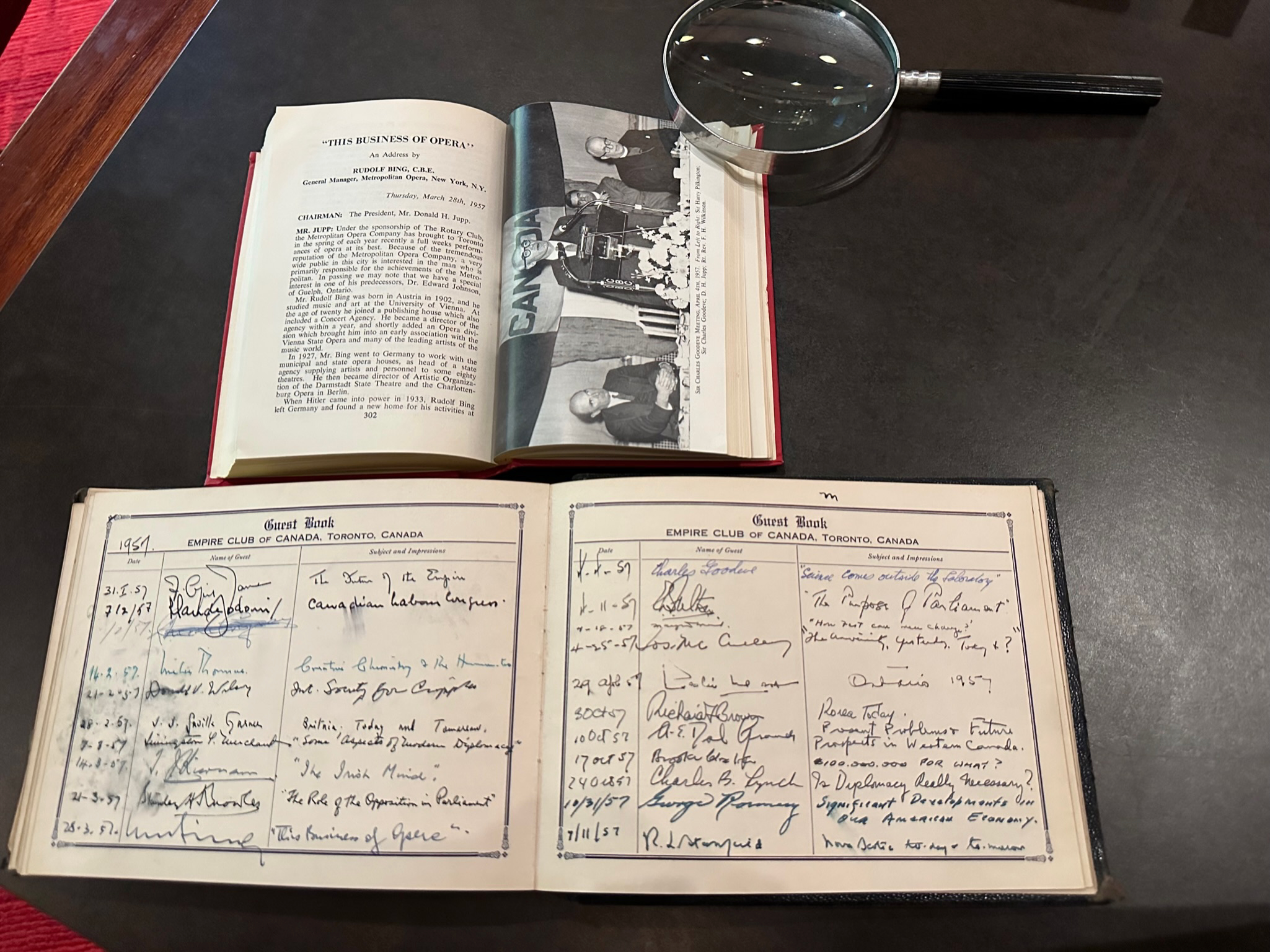

CHAIRMAN: The President, Mr. Donald H. Jupp.

MR. JUPP: Under the sponsorship of The Rotary Club, the Metroplitan Opera Company has brought to Toronto in the spring of each year recently a full weeks performances of opera at its best. Because of the tremendous reputation of the Metropolitan Opera Company, a very wide public in this city is interested in the man wbo is primarily responsible for the achievements of the Metropolitan. In passing we may note that we have a special interest in one of his predecessors, Dr. Edward Johnson, of Guelph, Ontario.

Mr. Rudolf Bing was born in Austria in 1902, and he studied music and art at the University of Vienna. At the age of twenty he joined a publishing house which also included a Concert Agency. He became a director of the agency within a year, and shortly added an Opera division which brought him into an early association with the Vienna State Opera and many of the leading artists of the music world.

In 1927, Mr. Bing went to Germany to work with the municipal and state opera houses, as head of a state agency supplying artists and personnel to some eighty theatres. He then became director of Artistic Organization of the Darmstadt State Theatre and the Charlottenburg Opera in Berlin.

When Hitler came into power in 1933, Rudolf Bing left Germany and found a new home for his activities at the Glyndebourne Opera, founded by John Christie, in England just at that moment. The Hitler war interrupted these festivals but Mr. Bing was asked to plan for their resumption in 1944, and in fact, Glyndebourne re-opened in 1946.

Meanwhile, the bold conception which developed into the Edinburgh International Festival of Music and Drama was forming in Mr. Bing’s mind and came to fruition in 1947 in association with the Arts Council of Great Britain and the City of Edinburgh. This annual event of world-wide importance was securely established when Mr. Bing accepted the appointment of General Manager of the Metropolitan Opera on June 1, 1950.

Mr. Bing has been awarded honorary doctorates from two American colleges–Dickinson College made him a Doctor of Humane Letters, and Lafayette College–a Doctor of Music.

Since Mr. Bing became a British Subject during his long residence in Great Britain he was eligible and was named a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the Queen’s New Year’s list in 1956.

It would be out of place for me to mention either a few of the innovations and improvements made by Mr. Bing at the Metropolitan in view of the title of his address to us, which is “This Business of Opera”, but because he has established a tremendous reputation in this respect, I hope that when he speaks to us now he will reveal some of these to us.

MR. BING: It is always a pleasure to return to Toronto and particularly, on this occasion, to be the guest of the Empire Club. Toronto is still the wonder city of our tour. It is the city where we not only thought but said, “It couldn’t be done”. But a stage rose in Maple Leaf Gardens and somehow a gridiron appeared from which we could hang any of the scenery we carry.

When people ask me what I think of opera in Maple Leaf Gardens I reply we only hope ice hockey will look as well in the Metropolitan Opera House.

Quite seriously, we would never have believed that our performances would have ever been so successful in the Gardens. In all our tours we have had to use amplification in less than six cities. Your equipment is by all odds the best.

And I feel I must comment on the visual improvements from year to year. The new seats–but that is more than a visual benefit, isn’t it?–on the lower floor are most attractive and the lighting particularly appeals to me. There is nothing like a surprise pink gelatin over a bulb to smooth out the wrinkles and rejuvenate the complexion. Mind you, I am not speaking of the ladies of Toronto who require no such contrivances, but Toronto comes near the end of our tour and after seven and a half weeks of touring we of the company welcome any such artifice available to us.

You know, when the Met sets up shop in Atlanta or Dallas or Toronto, it isn’t just another road attraction coming to town. It is the world’s foremost operatic organization giving performances as nearly identical with those at the Opera House in New York as is humanly possible. To do this we have to carry 325 people in two special trains and twenty-two baggage cars of scenery and costumes. I think we can be proud of the repertoire we are offering together in Toronto this season, a Mozart work for the first time, two by Verdi and two by Puccini and the ever-popular “Carmen”.

And now let me come to my main topic for today–This Business of Opera.

You know of course the old saying “there’s no business like show business”, but I suggest when it comes to opera this should be changed to read “there is show business that is no business”. You know what I am driving at if you have ever read a financial statement of the Metropolitan Opera Association. Or, let me hasten to add, of any other opera company.

Speaking as I do to what I have been told is a group of pay-roll meeting executives, I can literally see the frowns going up on your foreheads. “What”–you say to yourselves= “do I really have to sit here and listen to a man who right from the beginning admits that he is running a business that is losing money every year? And what is worse. the fellow doesn’t even look as if he were ashamed of it!”

You are so right, gentlemen. Not only am I not ashamed of our deficit, I am indeed very proud of its being so small, nor do I think that opera has any business to be a business.

Let me illustrate what I mean when I speak of the Metropolitan’s deficit as a small one. Like everything else in this life, this is naturally relative but if I tell you that all the leading opera houses in Europe–such as the Staatsoper in Vienna, the famous La Scala in Milan, the Paris Opera House and Covent Garden in London–receive government subsidies ranging from one to several million dollars a year, that means simply that the gap between the expenses in these opera houses and the income from ticket sales is as high as all that. The deficit at the Metropolitan has been fairly consolidated between $_500,000 and $600,000 a year in recent years.

Now you have of course every right to ask, even admitting that relative to other opera houses our deficit is a minor one, why on earth must you lose that much money? You know no doubt that the Metropolitan Opera House is an extremely successful theatre as far as ticket sales, both by subscription and single tickets, are concerned. In fact, I venture to say that in selling as high as 95% of our capacity on the average for a 24-week season, we are achieving box office intake far better than any other opera house in the world, with the possible exception of La Scala.

This would seem to indicate that opera is a losing proposition wherever you go. Such is indeed the fact. Why? If I may try, before giving you some details, to give you the reason in a brief and concise simile, here it is: suppose you produce shoes and it costs you $4.50 a pair to make these shoes, but as it turns out you cannot sell them for more than $3.95–then nobody can see that this is a bad business. It also shows another thing very clearly which is this: the more performances you play, the more money you lose. I mention this because we are often asked why we do not play more than the 24 New York weeks we have been playing.

On the other hand, our income is really quite high. We take on average over $19,000 per performance–really not a bad intake as income goes in theatric enterprises.

What then is the answer? It simply is that opera is a frightfully expensive commodity, always has been and, if I may hazard a prediction, always will be.

Let me give you some of the factors that make opera; such a luxury item. If you go to a Broadway show in New York the orchestra will vary from 28 to rarely a maximum of 40 musicians. The Metropolitan Opera has an orchestra of 92 and this compares not too favourably with either Vienna of the Scala in Milan, both of which have considerably more. It might interest you to know that our payroll for the orchestra alone is in the neighbourhood of $15,000 per week. Then comes a chorus of 78 which again is substantially smaller than in some European opera houses, and their weekly payroll comes; close to $10,000. Then comes the ballet of only 36 which really is a fraction of the number the large European opera houses employ, yet it adds another few thousand dollars to the weekly payroll. If these figures seem a bit staggering they are by far not the biggest.

In order to use a good orchestra wisely and indeed to achieve a well integrated musical performance of the highest critical standard, you need good conductors. Some of them draw fees of $1,000 per performance which in terms j of what they can earn otherwise is low payment.

Now I have. not yet mentioned the solo singers: we have 90 to 100 of them, some of whom are paid by the week, some of whom are paid per performance. At the top I have, with some difficulties, until fairly recently, kept a $1,000 per performance maximum fee which again compares unfavourably to what, for example, La Scala in Milan can pay and of course cannot begin to compare with what some of these top artists earn in concerts or television.

If that sounds grim, please consider for a moment a factor which I am sure never enters into the budget of; a shoe factory and that is that for every singer who sings a performance I have to have a singer who doesn’t sin& that performance but has to be paid all the same. If that sounds insane to you, so it does to me, and so it is. But you simply cannot stake a $19,000 house on the extremely sensitive vocal chords of a singer, to say nothing of their nerves, moods and other indispositions. If any singer were to have a sudden sore throat at noon of a performance day, informed me (as indeed happens all the time) that he or she cannot sing that evening, and if I then did not have a substitute of preferably equal but otherwise at least acceptable quality standing by, what it simply would mean is that I have to cancel this performance refund $19,000.

I could go on with this tale of woe for a long time but 1 won’t except possibly to add that there is also such a thing as physical production which means the building and painting of scenery and the making of costumes. You may also have heard of stagehands and workshops. These are the fellows who build and paint the scenery and later on handle it for rehearsals and performances. They too get heavily paid and while they work very hard for their money the total figure for stage operations in the budget is a pretty staggering one.

Let me not go into any more details but let me give you one example all the same. We had three new productions for the last New York season, one of them a very charming and elegant French operetta. The costume budget for this production is in the neighbourhood of $65,000. Need I really add any more figures?

Well, gentlemen, you may have to take it from me that this state of affairs is unchangeable, that a deficit is the very life blood of opera and that we will have opera only so long as there are sufficient people around who love this crazy form of art sufficiently not only to come and pay for their tickets but also to chip in more substantially whenever we are in dire need–which is always.

I hope I haven’t bored you too much but even if I have I think I have done you a great favour: all of you will now go back to your executive desks and settle down comfortably and smugly pleased with the consoling knowledge that you at least are not making shoes at $4.50 that have to be sold at $3.95.

THANKS OF THE MEETING were expressed by Mr. Z. S. Phimister.