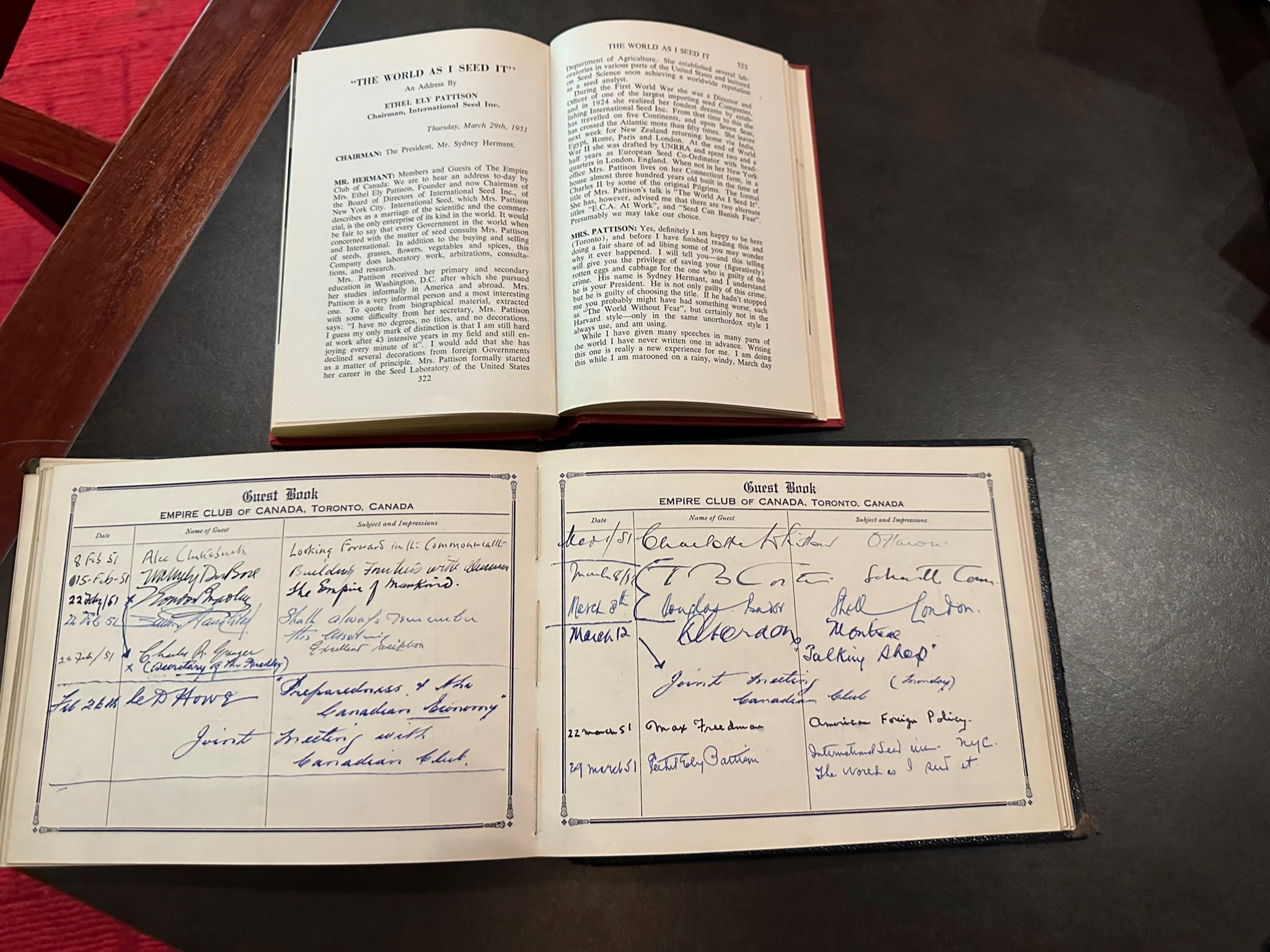

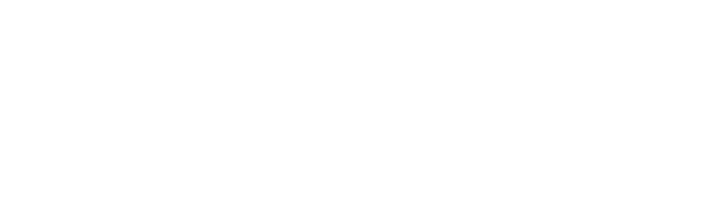

An Address By ETHEL ELY PATTISON Chairman, International Seed Inc.

Thursday, March 29th, 1951

CHAIRMAN: The President, Mr. Sydney Hermant.

MR. HERMANT: Members and Guests of The Empire Club of Canada: We are to hear an address today by Mrs. Ethel Ely Pattison, Founder and now Chairman of the Board of Directors of International Seed Inc., of New York City. International Seed, which Mrs. Pattison describes as a marriage of the scientific and the commercial, is the only enterprise of its kind in the world. It would be fair to say that every Government in the world when concerned with the matter of seed consults Mrs. Pattison and International. In addition to the buying and selling of seeds, grasses, flowers, vegetables and spices, this Company does laboratory work, arbitrations, consultations, and research.

Mrs. Pattison received her primary and secondary education in Washington, D.C. after which she pursued her studies informally in America and abroad. Mrs. Pattison is a very informal person and a most interesting one. To quote from biographical material, extracted with some difficulty from her secretary, Mrs. Pattison says: “I have no degrees, no titles, and no decorations. I guess my only mark of distinction is that I am still hard at work after 43 intensive years in my field and still enjoying every minute of it”. I would add that she has declined several decorations from foreign Governments as a matter of principle. Mrs. Pattison formally started her career in the Seed Laboratory of the United States Department of Agriculture. She established several laboratories in various parts of the United States and lectured on Seed Science soon achieving a worldwide reputation as a seed analyst.

During the First World War she was a Director and Officer of one of the largest importing seed Companies, and in 1924 she realized her fondest dreams by establishing International Seed Inc. From that time to this she has travelled on five Continents, and upon Seven Seas, has crossed the Atlantic more than fifty times. She leaves next week for New Zealand returning home via India, Egypt, Rome, Paris and London. At the end of World War II she was drafted by UNRRA and spent two and a half years as European Seed Co-Ordinator with headquarters in London, England. When not in her New York office Mrs. Pattison lives on her Connecticut farm, in a house almost three hundred years old built in the time of Charles II by some of the original Pilgrims. The formal title of Mrs. Pattison’s talk is “The World As I Seed It”. She has, however, advised me that there are two alternate titles “E.C.A. At Work”, and “Seed Can Banish Fear”. Presumably we may take our choice.

MRS. PATTISON: Yes, definitely I am happy to be here (Toronto), and before I have finished reading this and doing a fair share of ad libing some of you may wonder why it ever happened. I will tell you–and this telling will give you the privilege of saving your (figuratively) rotten eggs and cabbage for the one who is guilty of the crime. His name is Sydney Hermant, and I understand he is your President. He is not only guilty of this crime, but he is guilty of choosing the title. If he hadn’t stopped me you probably might have had something worse, such as “The World Without Fear”, but certainly not in the Harvard style-only in the same unorthordox style I always use, and am using.

While I have given many speeches in many parts of the world I have never written one in advance. Writing this one is really a new experience for me. I am doing this while I am marooned on a rainy, windy, March day at my farm in Connecticut without recourse to that pile of statistics which are filed in the office and stored in the loft and in other places such as the public libraries. Now we all, including myself, can say “Thank God”.

The world began to be seeded, according to the Hebrew legend, and not by me unless I was incarnate in Eve, a little over five thousand, seven hundred years ago by God, and it was the first thing He did after His two days of work making the Heavens and the Earth and the waters thereof. In fact it was on the third day. Chapter 1, Genises, V.12, reads “And the earth brought forth grass, herbs yielding seed after their kind and trees bearing fruit, within is the seed thereof after their kind, and God saw that it was good”. Despite all that I have seen men do in Seed I still am old-fashioned enough to believe that God, Allah, Jehovah, or whatever one wants to call the Infinite One, is the One with His evolution, wind, water, and other tools and powers, who Seeds the World and the Universe. One can pick up the same train of thought in the hieroglyphics and pictograph records of more ancient civilizations–those of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China, and if one is a geologist they can see Seed History in such really ancient ruins as the Grand Canyon of the Colorado, reported to be one million, five hundred thousand years old.

But as your delightful President, Sydney Hermant, has put “I” in the title of this speech I reckon I had better return to “I”. The title sounds autobiographical, and as the RAF used to say in World War II “You asked for it”, so don’t blame me. Here goes.

Fate, for want of a better name, pushed me into Seed at a very early age, and Fate–better defined just as “Necessity” and later as “Love”–has kept me in Seed for forty-three years, going on forty-four. I hope health and opportunity will keep me therein for another six, even if the last six will be as the Sphinx described on “Three legs”, and as many poets and doctors describe as “second childhood”. Having started in a simple capacity and having obtained the unofficial title of “Seed Queen” I shall not grumble if my last Seed jobs are “Charwoman Jobs”.

I can’t in any way be described as a “Career Woman”, despite the fact that had I the power to choose and relive I would not choose such things as “Prima donna” or “Ballerina”–I would choose “Seed”, for I do not believe love of any vocational profession would be as gratifying to the five senses and the spirit as the non-Parasitic profession, if one may call it that, of “Seed”. It has given me everything including the opportunity of living the full life of a woman. Now don’t hold your breaths, I am not going to launch into recital of my feminine secrets. If you were all younger–say college age–and if there was to be a question and answer period after this talk, the first thing the girl students would ask is “How did you manage to specialise in both Seed and Men at the same time”, and my answer always starts out with “It’s easy”, but that’s not where it ends. It ends with “Not without courage”.

Granting that I may have been born with one gypsy foot, I wasn’t conscious of it until at the Seed Laboratory of the United States Department of Agriculture I was fortunate enough to begin looking at, and separating Seed samples, on Seed characteristics, that were sent in–through, of course, the “Proper Official Channels” by such outstanding plant explorers as David Fairchild, and if there be any who have not read his autobiography “The World was my Garden” I recommend its reading. It doesn’t tell ten percent of his great deeds and even today I thrill over the great opportunities I had to even see a tiny bit of his great explorations in the form of seed from all over the world, and to know that I have now been to many lands from which they came. To spend some part of one’s life in such out-of-the-way places as Turkestan and to stand at a point east of the Aral Sea and behold fields of Alfalfa that had been there since before Alexander of Macedonia, who in BC 334 began one of the greatest continuous marches in history, to know that Alexander picked a plant of Alfalfa and sent it home to his Tutor Aristotle to become, by legend or fact, the first plant in a real plant herbarium. To be there to arrange seed material to be sent to USA for that Senior Agronomist, now dead, Harvey Westover, and eventually to become breeding stock for some of our wilt-resistant strains, still thrills.

These kinds of memories are more thrilling than those of being successful in buying five hundred tons of seed and earning two percent commission. Of course, the family would have starved to death and the business gone into bankruptcy had not the profit been earned.

When one looks at the history of Agriculture, of which Seed is to my way of thinking No. Al priority, it is hard to realise in these days when there are so many Agricultural Schools in the world, that the first agricultural school, that of Gembloux, Belgium, is hardly over one hundred years old, and the pioneering effort in the USA didn’t begin until 1850 (Michigan, please take a bow). Seed Science, or Seed thought of world-widely, is, of course, very young. Now I wasn’t in at the beginning and while I remember the old tales I wouldn’t go on record of just where, when, by whom, it all started because I would have dozens of people on my head denying this and claiming that. It’s enough just to realize that it is fairly young, and the surface hasn’t been but barely scratched. Some of the scratches have been rather deep, and have brought forth many marvellous results, and hold great promises for the future.

My part in this magnificent seed drama, in which I have been on the stage these forty-three years, has been a very minor one, and the best that can be said of it is that it’s been in the roles of a catalyst, or co-ordinator, or a tramp. I haven’t any initials after my name or any prefix before it, and I wear no symbols of honours on my chest, although I modestly confess I turned down one or two which would have been presented if I had said “Yes” to the overtures.

The first word of the title is “World”, and I have seen a fair part of it-five Continents and Six Seas, and I am soon to see the Sixth Continent, Australia, and the Seventh Ocean–the Indian. All that will be left then is Antarctica and the Antarctic ocean. I have been several times above the North Arctic Circle. Most of the travel has been in monotone “Seed”, but the tempo has been the profit-motive, except those years such as 1944/45/46 when I tried to do my part in the role of UNRRA’s European Seed Co-Ordinator.

Instead of going on with a short recital of my “Seeding the World” as UNRRA’s Seed Co-Ordinator I will take a few minutes to speak of a dramatic period of about five years–or maybe I had better say ten-thirteen years. There was five years’ travelling in the various Republics of the USSR–but there were years previous to this block of time where interesting agricultural work was done more or less sitting on the sidelines, and then, years after, as UNRRA’s Seed Co-Ordinator, much thought and time had to be given to the two USSR Republics, Byelorussia and the Ukraine. Russia was always, and is today, an area intriguing the minds of those of us in Agriculture. I amusingly confess that my first knowledge of Russia came at the age of four, from the famous pianist Paderewski at a time just after he told the Czar of all Russias, following a Command Performance, that he was not a Russian, he was a Pole–and Poland then belonged to Russia. It took me quite some time to find out that Russia was really a country and that being a Pole was something other than one who walked on pole sticks. But my first agricultural intriguement came about ten years after the greatest of Cerealists, Mark Carleton, went on his famous search for rust-resistant wheats in the Black Lands of Russia (principally Ukrainia and the North Caucuses), and he found them there and brought them back, which resulted in revolutionising wheat production and milling. There is hardly a time when I eat a piece of bread that I don’t think of Mark Carleton of the United States Department of Agriculture, and Russia, and I in the late Twenties played a part in the collection of American wheat with Russian blood therein in order to rehabilitate Russian wheat acreages with good wheat after everything had fallen into complete chaos from World War I and the Russian Revolution. When Mark Carleton went to Europe in 1898 scientists were predicting that by 1931 the increase in population would overtake the possible production of wheat as then grown. I have not seen the figures of the last eight years of Wheat Production of the World–not those of my country nor yours–but one only has to look back to the figure of 1907, when the wheat production in the United States was but forty-five million bushels, and this was on an average yield per acre of twelve to eighteen bushels compared with an eight to ten bushel average yield of just ordinary wheat; and at the time that the then-called “Seed and Plant Introduction” was founded our generous Congress gave Mr. Fairchild the unheard of sum of twenty thousand dollars to do the job, and this twenty thousand dollars not only had to run the office and pay all the expenses, but had to cover all the expenses of the plant explorers such as Fairchild, Carleton and Swingle. In helping to collect these wheat strains in America for USSR, mostly for purely private-enterprise profit motive reasons, certainly never from ideological reasons, I get a little breathless, and probably somewhat worried, when I think that USSR doesn’t only produce enough wheat for its own consumption of more than two hundred million people, but has those large exportable surpluses which it can dump on the world market as it did in the early Thirties and break the market, or, as it can now, with bilateral and other Treaties, deliver huge quantities of grain to such as our Mother Country. At that particular time I was travelling with quite a noted Soviet Citizen, who has since been liquidated, who was not geared to Americanski tempo and was somewhat provoked over my haste and worry, and who taught me a Russian proverb which I have continued to use in my life and in my vocation, Seed–“In one minute anything happens”. This is a very helpful proverb if one can always play the role of an optimist.

Besides helping with the establishment of the wheat acreages and the movement of this wheat acreage northward out of the drought areas I played a small part in the movement of Ukrainian Red Clover and Turkestan Alfalfa westward, the building of the Soviet Florida on the Black Sea, the establishment or extension of such cultures as Soybeans, Peanuts, and Cotton, and a little in the mechanisation of Soviet agriculture. On these trips to USSR, where I wandered around in both the European and the Asiatic parts, as well as those above the Arctic Ocean, and those known as Subtropics, I witnessed firsthand the great tragedy, and its results, known as the Agrarian Revolution; the breaking of the backbone of the Kulachs; the formation of great Collective and State Farms. We, who are in Seed for scientific or, commercial purposes can never forget–and, if we are good patriots, must never forget–the agricultural potentials of USSR and the now-called Satelite countries, all of which I have seen not once but many times.

Returning to the item “Wheat” and before I go on with a little travelogue about UNRRA I should like to mention one fantastic piece of Russian work which still intrigues the Russian scientists, and that is Perennial Wheat. The Russians broke the theory that only “species” and not “genus” could be crossed, and they did manage to cross one genus with the wheat genus Triticum and produce a Perennial Wheat. Nothing of any commercial or economic value has come out of this work, but it still is not neglected, and I believe there is some work on this Perennial Wheat now going on in many places in the world such as Finland, Sweden, Italy, and Switzerland, and while I have seen some of this in the countries just named I think Canada can be added to this list, because I have within the year seen some pictures of Canadian Experimental plots of Perennial Wheat. (At the Experimental Station, Ottawa). There may be nothing to this idea of Perennial Wheat, but it’s a good hitching-post where one could hitch a dream. Just think if there could be something such as Perennial Wheat or for that matter any of the cereals produced in gigantic quantities throughout the world what would be the result. Well it would make our present statistics and forecasts look just as absurd as the forecast of the scientists in 1898, and those of Malthus in the early Nineteenth Century, and those of some of our present pessimists of the mid-Twentieth Century. Well, there may never be a Perennial Wheat of any commercial value, but it still has its possibilities and it is a dream of what science may yet do in Seeds through genetics and other scientific roads. We do not need to be worried because there is not enough land or there is not enough brain, or there is not enough yet to be discovered. All we have to do is to first dream and dream straight, and then do, and I hope to look back, after I am no longer any good as even a Charwoman, on the things that are being done in Seed, and the seeds of so many things which are growing in many parts of the world, and which are yet to be discovered and brought forth, such as Sorghums and Sudan Grass have been in the last half-century.

Perhaps the procurement of Seed and its distribution for the Agricultural Rehabilitation Programme, which took only two-and-a-half years (it’s too bad that it wasn’t longer and wider) will paint in not too-many strokes the most graphic picture of Seeding the World. Such questions as where to get the seed, when seed was scarce, and the money with which to pay for it when money was scarce; how to move the seed and how to distribute it for the greatest results, are only a few problems which confronted me. The absence of Time in which to do a big job, and the ever-present thought that if the job wasn’t done timely thousands of people and animals would starve, really were the factors that put the grey hairs in one’s head. The job was done, and most of it Timely. It would take more than a mathematician and all sorts of gadgets to estimate the results in tonnage or calories, and there is no way of estimating the uplift Seed gave the hopeless populations.

UNRRA was the first United Nations effort, and I believe it started with something like forty-four countries united, and closed with a number above fifty. Some were so-called “paying” countries–yours and mine belonged in that category–and some were “non-paying”, and these are the ones which received the Seed. The Head Office of UNRRA was in Washington, the Head Regional one in London, and then came the country offices in the capitals of the countries. All had to be visited more than once. These two-and-a-half years were continuous flying circuses in more ways that one. Seed was literally gathered from the Six Continents and crossed the Seven Seas. And in Europe the paths made a gigantic spider’s web, for even the poor war-torn countries often had exportable surpluses which some other country needed–e.g. Italian Alfalfa needed sadly by Yugoslavia; excess of Czechoslovakian Seed Rye screemingly needed by Poland, but only to be given up if ton for ton was paid with wheat plus a dollar bonus; Cyprus seed potatoes, which the Cypriots would rather let rot unless an exhorbitant price was paid, for they knew there was no place else to get them, while the Greeks would be left starving if we didn’t pay through the nose. It would take too long to name all the countries of six Continents from which we drew Seeds of our seven categories–Cereals, Industrial, Vegetable, Forage, Root, Fibre, Miscellaneous, which included everything from seeds for production of medical needs, to seeds for reforestation purposes. To name the seeds would take too long a list, for there were hundreds of items. I think it can be said that UNRRA contributed about eighty-four million dollars’ worth of Seed, and more than a fair chunk went to such Iron-Curtain countries as USSR, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. Greece and Italy also got their fair share.

Along with such hard work as moving seven thousand tons of Seed Rye in three weeks from one country to another when railroad cars and locomotives were almost invisible, bags and twine equally so, and the hatred of centuries in the European blood, and then to replace these seven thousand tons with milling wheat from three Western-Hemisphere countries (Canada, USA and Argentina), there were dots of humour such as Yugoslavia thinking Alfalfa seed was something from which to make medicine, and some stupid Army Officer in the British Zone of Germany thinking it should be used (and I think it was) for breakfast food for the Germans, and a modest secretary who tried to talk me out of attending Staff meetings because that which was being discussed was artificial insemination and bred heifers and this was no talk for a lady’s ears.

And it wasn’t all humour and work; sometimes there were moments of anxiety such as being in the Alps at eighteen thousand feet elevation and having the C.47 a target for some frisky Yugoslav pilots’ firearms.

Now with your kind permission I am going to rephrase the title, making it read the “World as I see It” and talk about this in the few minutes which are left.

I don’t belong to either the Malthusian or the neoMalthusian groups. I don’t believe that poverty and distress are unavoidable since population increases by geometric ratio and the means of subsistence by arithmetic ratio. I firmly believe with continued enlightenment and science that there is enough brain, land and resources to produce more than enough subsistence for man and beast for many times the world’s present population; and those who live with Seed can visualise what can yet be done, not only to make two blades grow where one grew before, but make a hundred grow, each one a hundred times greater than the original.

And I don’t believe in the dismal forecast of the German philosopher Oswald Spengler, who held at the beginning of this century that Western culture is approaching its death. I do hold with him, on the basis of history, that every culture passes through a cycle from youth, through maturity and old age, to death. Where I disagree with Spengler is that I don’t think that this is the “old age” period of our culture. I hold that it is youth, if not infancy, and, therefore, I see a long path forward through youth, to maturity and old age. Centuries to think about and centuries in which to do. And one of the many things we have had right in front of our noses, and in which we have had too much lag, is Harry Truman’s Point 4–the sharing of our technical aid with less fortunate countries. This really isn’t an idea originating with Truman, but I am never as much interested in who originated an idea as I am in the doing thereof, and certainly in this technical aid programme, whether it be done by the US or the UN, (maybe it can be done both ways). Seed certainly should be the A1 Priority in agriculture. It is pleasing to us who have watched this development to know that at long last Nelson Rockefeller, who heads the Board, has made the Board’s programme public.

Now the thirty minutes allocation is up, and I haven’t touched on such Continents as Africa and South America. Maybe at some distant date, after I have finished Australia and New Zealand, to which I fly on April 8th, I can come back and talk about the Southern Hemisphere.

VOTE OF THANKS, moved by Lieut-Col. N. D. Hogg.