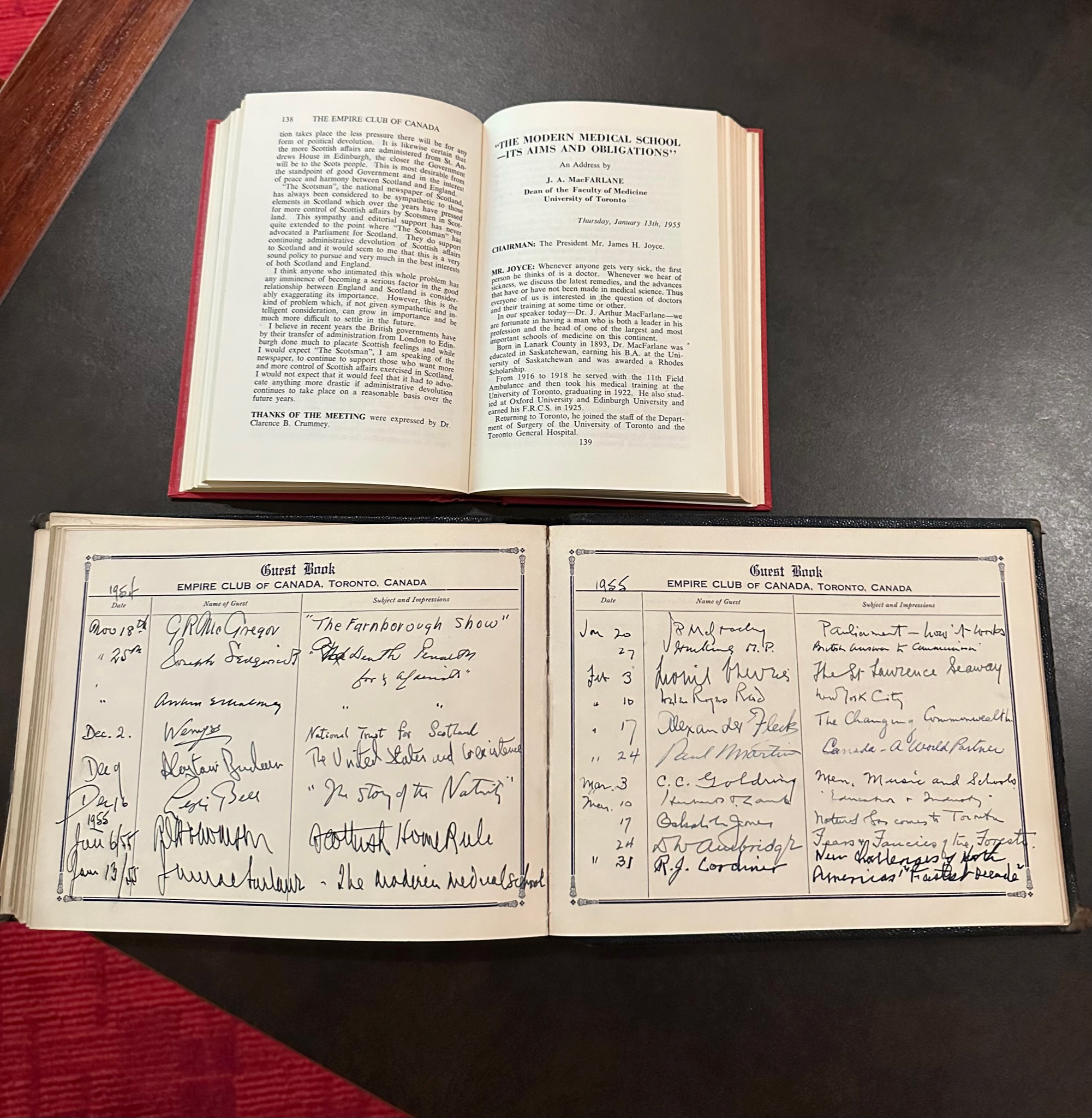

An Address by J.A. MacFARLANE Dean of the Faculty of Medicine University of Toronto

Thursday, January 13th, 1955

CHAIRMAN: The President Mr. James H. Joyce.

MR. JOYCE: Whenever anyone gets very sick, the first person he thinks of is a doctor. Whenever we hear of sickness, we discuss the latest remedies, and the advances that have or have not been made in medical science. Thus everyone of us is interested in the question of doctors and their training at some time or other.

In our speaker today–Dr. J. Arthur MacFarlane-we are fortunate in having a man who is both a leader in his profession and the head of one of the largest and most important schools of medicine on this continent.

Born in Lanark County in 1893, Dr. MacFarlane was educated in Saskatchewan, earning his B.A. at the University of Saskatchewan and was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship.

From 1916 to 1918 he served with the 11th Field Ambulance and then took his medical training at the University of Toronto, graduating in 1922. He also studied at Oxford University and Edinburgh University and earned his F.R.C.S. in 1925.

Returning to Toronto, he joined the staff of the Department of Surgery of the University of Toronto and the Toronto General Hospital.

During World War II, he was consulting surgeon with the rank of Brigadier to the Canadian Army Overseas.

In 1946 he was appointed the first full time dean of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Toronto, a post he still fills. Since 1945 he has also been director of surgery at

Christie Street, which is now Sunnybrook Hospital and consultant in surgery to the Department of Veterans Affairs.

He will speak to us on “The Modern Medical School–Its Aims and Obligations”.

DEAN MacFARLANE: It may at first thought seem rather strange to you, that the Empire Club should devote one of its meetings to a subject such as a medical school. There is, however, no lack of public interest in medical affairs. Indeed, it was a trite remark, that the average doctor must not neglect his week-end reading of “Time” or the “Reader’s Digest”, and other lay magazines, if he would be as well informed as his patients. I hope then, that I may for a few minutes interest you in that centre in your own metropolitan area, in which doctors are born, medical investigation is fostered, and where a group of men and women devote their time to teaching and research, and in a general way to keeping their fingers on the pulse of the community and of the nation.

It is true that as early as there is any record of human scholarly effort there seems to have been an interest in the study of medicine. In the earliest writing of Egypt, of Arabia, of Greece and Rome there are many references to it. Frequently they are associated with philosophy or religion, and indeed, that is not difficult to understand. Most medical theories in those days were the result of philosophical speculation rather than of scientific investigation. Here and there down the ages schools were established, frequently as the result of the teaching of some single great scholar, who unfolded a little further the riddle of the human body and its anatomy and physiology. Sometimes the schools were associated with universities; sometimes they gained renown as independent centres of scholarship and learning.

Only towards the middle of the 18th century was the scientific method beginning to affect seriously the study and practice of medicine in the western world, and great schools were established in Britain and on the Continent. It may be interesting to review the development of medical education in the United States, for, to a lesser degree, the same influences were at work in Canada.

With the rapid development of the United States, and the increasing knowledge of medicine, medical education for a time became a field-and a very profitable one–for private enterprise. No laws governed the entrance qualifications to these schools. A degree from a proprietary school admitted the successful candidate to unrestricted practice. Between 1809 and 1909, 457 medical schools were established in the United States and Canada. 155 were still in operation in 1909. The majority of these had no relation to a university. They advertised for students; there were few admission requirements; instruction was a series of didactic lectures; the course lasted one or two years. The fees covered all the expenses and usually the schools were able to declare a profit. As soon as they failed to do so, they closed their doors and their sponsors departed for greener fields in the newer western towns. The movement was largely American in origin, and the corrective effects of the better American students who had studied in Britain, Holland and France became gradually apparent.

In 1907 when Abraham Flexner of the Johns Hopkins School undertook, with the sponsorship of the Carnegie Foundation, a survey of medical education in the United States and Canada, the corrective measures were already in operation, but the report clarified the situation with clear-cut recommendations; namely: the return to the basic sciences as the only foundation on which to build an education in medicine; the maintenance of reasonable standards of entrance; the association with universities, and the recognition by the universities that the establishment of a faculty of medicine carries with it the responsibility of financial support far beyond the amount which is represented by the fees collected from the students; and finally, the association of medical schools with hospitals under the educational control of the school.

What changes have been wrought in less than half a century! The Flexner report was written in 1909. It altered the whole approach to medical education in the United States. The system which we had developed in Canada had always derived much more of its tradition from Britain and France, but undoubtedly was, and continues to be, influenced by the recommendations of this report.

Each of the twelve medical schools in Canada is an integral part of a university, and the degree conferred on successful candidates is the degree of that university. Each school has an arrangement or agreement with one or more hospitals, whereby it can carry on clinical teaching in the wards, laboratories and out-patient departments of such hospitals. The admission requirements vary slightly, but curriculum requirements throughout the course are such that candidates from each of the twelve colleges are eligible to try the examinations of the Medical Council of Canada, which gives the successful examinee the right to register and practise in any province in Canada.

What then are the objectives of a medical school? Certainly one of the first is the basic training of young men and women in the profession and art of medicine. After two to four years of preparation in college work, the average student begins his professional programme at about 21 years of age. In the succeeding four years, beginning with the basic studies of anatomy, physiology and biochemistry, he progresses by well planned stages towards the final year, when all his instruction is given in the wards and lecture theatres of the hospitals. It is not difficult to understand that those responsible for planning this basic course of undergraduate training must continually revise the curriculum in the light of new researches in human physiology, chemistry and pathology, and the tremendous advances in the understanding and treatment of disease which have resulted from such investigations, particularly in the past 40 years.

What is the place of a Canadian medical school in the national life of Canada? To answer this question it might be profitable to examine our own school, for although it may differ from others in certain details of organization and practice, it will serve as a reasonable example when considering aims and objectives.

This school is one of the largest on the continent. Each year approximately 150 young men and women complete their undergraduate course. Until the opening of new faculties in the west and at Ottawa, the Toronto school produced approximately 25 percent of the new Canadian graduates. Even now the annual output is about 17 percent of the newly qualified doctors in the nation. There are at present nearly 6,000 living graduates, and in the last ten years we have qualified some 1,500 doctors. However, this task is but a part of the three-fold responsibility of a modern medical school in the western world. As well as a source of sound and progressive undergraduate teaching, it must be the spearhead of research, and it should also be a centre for postgraduate education of specialists in various fields, as well as a community centre of continuing education of the practising physicians in the area which it serves. Its realm of influence in this last function will, of course, vary with the nature of its scholarship and research, and the degree to which it wishes to assume such a responsibility.

Medical schools are being perpetually confronted with new and difficult questions, which challenge the enquiring mind. They are not only the repositories of the knowledge accumulated through centuries of effort, but the principal sources of new medical knowledge. Research is no longer a superimposed function, but has become an integral part of the school’s daily life. Investigation, enquiry, the search for truth-these are of necessity the very essence of sound teaching. A review of the annual report from the school, and the list of publications, will show the diversity and the scope of research which is carried on in the eighteen teaching departments, and in the special department of medical research under the direction of Professor Best, whose work on insulin with Banting, McLeod and Collip gave such a tremendous impetus to the investigational aspect of medicine in this centre.

The increased demand for special postgraduate training, both in the basic sciences and in the clinical fields, is a reflection of the tremendous increase in medical knowledge and the diversity of techniques, and the recognition of the fact that only by long years of application can one perfect his knowledge and skill in certain special fields. In a measure it reflects also the maturing of Canada . as a nation. When I finished my undergraduate course a little more than 30 years ago, forty per cent of a large class left immediately for the United States. The reason there were insufficient hospital interneships in this country, and few opportunities for intensive postgraduate training. At the present time there are still those who seek their hospital training in the United States from choice, but there are more than enough interneships in Canada to provide training for our newly qualified doctors.

In our own school and its associated hospitals at the present time, there are in training for the various specialties, in programmes which take from three to five years, some 250 doctors. Some will take higher degrees in the School of Graduate Studies in the University; others will qualify for specialist diplomas of our own school; others will enter the teaching or research field here or elsewhere; and a large number will take the examinations of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons in Canada.

As well as the specialist training programme, the school provides annually several short courses for practitioners. These vary in length from three days to six weeks. It carries on a programme of decentralized postgraduate education in six other towns or cities in the province, by sending out teachers who spend a day with the doctors at the community hospitals, leading discussion groups on problems presented by the local doctors themselves.

To effect this diversified task, the Faculty of Medicine, as a division of the University, functions through its eighteen teaching departments–each with a considerable degree of autonomy, but linked to the other departments–through several committees, and in an overall Council on which sit some 150 members of the teaching staff. Moreover, there are close relations to many of the other schools, faculties, and institutes which are interested in the problems of health: the School of Hygiene which fosters the teaching and investigation in public health; the School of Nursing; the Faculty of Dentistry; the Institute of Child Study; the Faculty of Pharmacy; the School of Physical and Health Education, and the School of Social Work. It offers through many of its departments, instruction to students from several of these faculties. The students in Dentistry come to us for their anatomy and physiology; the students in Pharmacy come for their instruction in pharmacology. Students in certain honour courses in the Faculty of Arts come for biochemistry and physiology. The Faculty of Medicine also includes a Division of Physical and Occupational Therapy of some 275 students. The Department of Art as Applied to Medicine offers a course in medical illustration, and at the same time provides an art service for the other departments of the Faculty.

The doctors who are members of the staffs of the teaching hospitals assist in the teaching programmes of the Nursing Schools which are associated with those hospitals. The specialists in Radiology teach classes of radiographers. Pathologists assist in the teaching of laboratory technicians, and, indeed, this is as it should be. Doctors are keenly interested in the training and welfare of all those who seek careers in these and the various other vitally necessary ancillary services.

The physician who commits himself to the discipline of a teacher and investigator in a modern school assumes a variety of tasks. As he grows older, he must take his place in the learned and professional societies, both national and international, which have as their objective the furthering of knowledge in his particular specialty. If he is in the clinical field, he will be interested in the welfare and expansion programmes of the hospitals with which he is associated. He will inevitably be sought as adviser or committee worker on the various community, provincial and national organizations, that are an essential feature of the present day social fabric of our nation.

I should indeed be remiss if, in speaking to a group of men, many of whom are interested in finance and administration, I failed to say a word about the financing of such a complex structure as the modern medical school. I referred earlier in my remarks to the close association of medical schools with universities. Indeed, since the publication of the Flexner report, no medical school in Canada has tried to exist except as an integral part of a university. The finances for the everyday necessities of a school–as indeed for all the divisions of a university–come from three sources: the fees paid by the students; private endowments; and government grants. The fees, high as they are in most medical schools, meet but from one-fifth to one-third of the annual budget. Income from private endowment in our own school provides approximately 5 percent; income from fees approximately 30 pe cent, while the remainder comes from the University, which, in turn, must look to provincial or federal sources. There is no separate grant from either provincial or federal funds towards the ordinary budget of the medical school. On the other hand, fairly liberal grants are available from various sources, for the prosecution of research. These sources include the National Research Council, national and provincial cancer organizations, national life insurance funds, private foundations, provincial and federal Departments of Health, and the Defence Research Board. Bricks and mortar, alterations, replacements–these must come from private funds or special government grants. Equipment of new buildings and laboratories may be supplied through provincial and federal grants, but when the buildings are completed, the heating, the lighting, the replacement of equipment, the staffing, all these represent increased obligations in the annual budget.

It may well be asked by business men, why a school should sell valuable service for less than it costs to produce it. In other words, if tuition fees produce only a fraction of the cost, why not raise the fees? These indeed are already so high that schools are beginning to wonder if certain bright young students coming from the families of artisans or farmers, may not be discouraged from enrolling in medicine. Annual fees in Canada vary from $450 to $600; in the U.S.A., from $600 to $900. The Americans’ estimate of cost to produce a doctor is in excess of $13,000. The cost in Canada may be somewhat less, but I venture to say, even the American figure is less than that which it costs to produce a jet pilot, to say nothing of the machines which the pilot needs to make his skill effective. Other American figures indicate that medical colleges in that country absorb 30 per cent of the total budgets of the universities of which they are a part, although they enroll only 10 per cent of the total student population. In Toronto, the medical student population is under 10 per cent of the total enrollment, and it takes approximately 15 per cent of the total university academic budget. I can assure you, in Canada at least, the salaries of teachers in medical schools are not excessive, and indeed, the majority of the clinical teaching is carried on by practising specialists who devote a great deal of their time to teaching and public ward work for a nominal honorarium.

The American medical educator is not anxious to seek either state or federal aid, fearing the possibility that state support will result in some degree of state direction. There are currently two large funds in the United States, one seeking donations from large corporations, and the other from the profession, both funds being available to help meet the annual deficits of medical schools. These funds, of course, are exclusive of the many other sources for research and investigation.

My attention has been drawn recently to an advertisement in the New Yorker Magazine. This advertisement is sponsored by a large American corporation, and states that one out of every two colleges and universities in the United States is operating under a deficit, The company encourages college trained men who work for it to contribute to their college deficit fund, and promises to match these donations, dollar for dollar, up to a thousand dollars per year.

I think I can speak for Canadian schools; they do not fear any malign influence in money which comes from provincial or federal governments; they have not been embarrassed by such support; and although they welcome private endowments and private support for special projects, the ever-widening gap between income and expenditures can only be closed by solid and continuing government funds, if the schools are to carry out the functions which the public expects, and their tradition demands. The plan in Britain whereby grants are made on a five year basis through the university grants commission, has worked satisfactorily. After several years experience under both socialist and conservative administration, I have heard no murmur from British educators, of government interference with the sound basic principles of medical education in that country.

I have welcomed the opportunity to tell you something of this educational institution that is in your midst-an organization that inevitably through its work and influence reaches out and touches the every day lives of most of you at one time or another. Canada has already no small reputation for the quality of medical service available to its people, both in peace and war. The advances of modern medicine, the organization of society to bring good medicine to the nation-these are topics frequently before the public in the lay press. Canadians expect the best from their doctors and from the schools which train them.

The teaching of the art and modern science of medicine to a succession of young undergraduates; the sponsorship of modern research, ever reaching out for more space, more complex and expensive equipment, more skilled technical assistance; the planning of postgraduate education and specialist training in the light of an ever-widening field of knowledge and techniques; the encouragement of a spirit of leadership in its young teachers and investigators, and finally, creating a source of advice and sound judgment in community and national affairs that touch on the health of the people–these are the principal objectives of a medical school in this twentieth century.

It is a somewhat different conception to that of a school at the beginning of the century. That it is costly in comparison with those schools in the early 1900’s, when even modest student fees were sufficient to balance the budget, there is no doubt. You, who can look back over the half century and consider but a few of the everyday facts in relation to the great strides towards prevention of disease, and the revolutionary advances in treatment, can best judge whether in this modern conception, the increased costs of medical education are justified.

I need hardly remind you of what the advances in medical research mean to the present generation. The statisticians tell us its effect on the population in the mass. Here are a few figures from British sources, and I am sure that Canadian figures would not differ greatly.

The expectation of life at the time of birth has increased in 50 years by 181/2 years for boys, and 21 years for girls. The girl child of today who has reached a first birthday has a life expectancy of 71 years, and the boy 66 years. Diabetes and pernicious anaemia and many other diseases are under control. The common infections that were the major causes of illness in the early part of the century can for the most part be controlled, if not eradicated. On the one hand there are the great advances in preventive measures: typhoid and diphtheria are almost forgotten diseases in this generation of Canadians. And, on the other hand, there is the tremendous advance in the treatment of active disease by new drugs, by a better understanding of the underlying physiology, biochemistry and pathology. No longer is lobar pneumonia the winter scourge of the Canadian community. It is rare indeed to hear of death or even prolonged illness from blood poisoning. With the aid of new methods of anaesthesia, blood transfusion and other supportive measures, the surgeons have succeeded in attacking disease in areas of the body which were denied them at the turn of the century–the chest, the brain and the central nervous system, and the heart. There has been in evidence a new and encouraging approach to psychiatry and mental health. But all that is another story.

Modern medical schools produce the doctors who are versed in the new methods of diagnosis and treatment, the family doctors who will care for you and your children. Medical schools are the nurseries for doctors, but they also remain their professional homes–homes to which they return for renewal and revision of knowledge. They are by far the most important sources of the workers who engage in medical research. This golden age of medicine in the first half of the twentieth century is contemporaneous with the new concept and reorganization of medical schools. Who will say they are otherwise unrelated?

I have made some reference to the public interest in medical affairs. One’s own interest turns quite as naturally at times to fields other than medicine–the ever increasing expenditures on entertainment and amusement, the increased demand for motor cars and the costs of new roads to carry them, the costs of primary and secondary education, the fantastic growth of our economy, with increasing demands for scientists, trained executives and professional men, and finally, in comparison, the relatively small expenditures on higher education.

This country will need trained leaders in every field in ever increasing numbers. The universities are the training grounds. It remains for the citizens to decide to what extent the institutions of higher learning, including the medical schools, shall continue to thrive and expand, unfettered by insecurity, and unhampered by financial stringency.

THANKS OF THE MEETING were expressed by Mr. Alexander Stark.