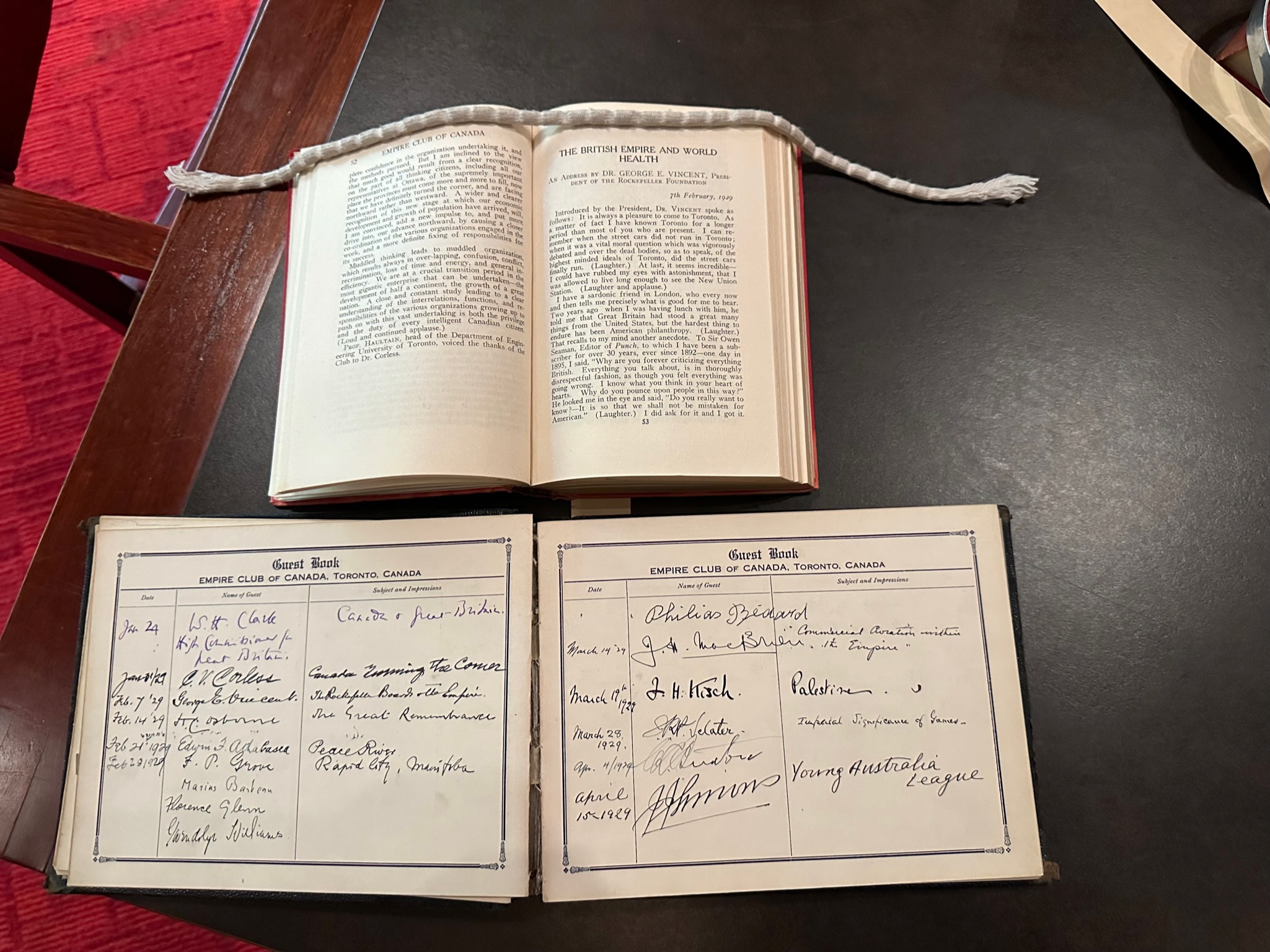

AN ADDRESS BY DR. GEORGE E. VINCENT, PRESIDENT OF THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION

7th February, 1929

“Introduced by the President, DR. VINCENT spoke as follows: It is always a pleasure to come to Toronto. As a matter of fact I have known Toronto for a longer period than most of you who are present. I can remember when the street cars did not run in Toronto; when it was a vital moral question which was vigorously debated and over the dead bodies, so as to speak, of the highest minded ideals of Toronto, did the street cars finally run. (Laughter.) At last, it seems incredibleI could have rubbed my eyes with astonishment, that I was allowed to live long enough to see the New Union Station. (Laughter and applause.)

I have a sardonic friend in London, who every now and then tells me precisely what is good for me to hear. Two years ago when I was having lunch with him, he told me that Great Britain had stood a great many things from the United States, but the hardest thing to endure has been American philanthropy. (Laughter.) That recalls to my mind another anecdote. To Sir Owen Seaman, Editor of Punch, to which I have been a subscriber for over 30 years, ever since 1892-one day in 1895, I said, “Why are you forever criticizing everything British. Everything you talk about, is in thoroughly disrespectful fashion, as though you felt everything was going wrong. I know what you think in your heart of hearts. Why do you pounce upon people in this way?” He looked me in the eye and said, “Do you really want to know?-It is so that we shall not be mistaken for American.” (Laughter.) I did ask for it and I got it where except Scotland. Those not necessary for perpetuating the race are sent into the Empire. Thus if something were done in Edinburgh, it would have a wide influence all over the British Empire.

When you come to London, there is one medical school which represents all the elements of a modern medical school on one side-University College Medical School, while Guy’s has a splendid Medical School. Only one place you have in London,-in Grace Street Medical School-with laboratories for patheological and bacteriological research. In Grace Street, you have a great hospital of six or seven hundred beds all under single management. There was an opportunity. In fhat impertinent or intrusive way which used to be characteristic of us we asked that we might be allowed to have a share. With sportsmanship which is characteristic of the British always they let us into the game. We said let us contribute £ 1,000,000 to that enterprise and the British did their part and they have contributed about £ 500,000 in addition to that enterprise, until there you have one of the conspicuous medical centres of the world. And it is a source of pride to us who have had just a little to do with it. University College Hospital is a part of that plant.

It seemed that something ought to be done in the way of getting a central site for the University of London which was scattered all over the place in about forty different units. There was some land, about 11 Y2 acres which was in the right position for the University campus. The Government provided some money and private funds were available. So this opportunity to make the whole thing worth while was taken by giving £400,000. The University of London has now one of the finest campuses anywhere in the world. We got more and more connections in London. Then the question came how best to utilize public health boards in England? So a plan was worked out by which we agreed to give land if the British Government would undertake to support. I was one of these who went over to negotiate just as the Lloyd George regime was coming to a fall and the Geddes axe was being wielded . Friends suggested that it was no time to suggest additional expense to the British Government. Sir Alfred Mond insisted on a hearing being given. “If it means maintenance for the future,” he said, “my colleagues should have an opportunity of expressing their views.” Cabinet immediately accepted the offer and agreed the necessary amount for maintenance. The next day I met Sir George Newman, Chief Health Officer of the Ministry of Health. I said, “There is a good deal of uncertainty about the Lloyd George Ministry. How about the next ministry?” “What do you mean?” he said. “Well,” I said, “suppose another ministry came in and did not approve of this plan and were not willing to go on with it?” I saw I had made a fatal blunder. “Why,” Sir George said, “I do not understand.” I did make it a little clearer. “Why,” he said, “No British Cabinet would ever think of going back on an agreement.” Well that was a little education for me. (Laughter.) There has been some delay in the construction. Next October, adjoining the University of London, this great school of public health will start off as one of the great centres for the training of public health in all the world. To that institution will be sent fellows from all over the continent in order to get instruction.

There is the medical school in Cardiff and more recently a program of public health was worked out in the Irish Free State. Co-operation is just being undertaken with both the National Free State and Trinity College in Dublin. We put our money on both horses at once. (Laughter.) We took no chances and are preserving what is known as ministerial neutrality. Well now we get through the British Isles. We strike Halifax–Dalhousie Medical School which is one of the best combinations of medical schools and public health centres, and turning out splendidly equipped men from the school which is well organized and admirably conducted. It was a pleasure to have something to do with the reorganization and endowment of that institution. You might say we are raising our own Canadians for our work.

In the province of Quebec with the co-operation of the Provincial Government in the French-speaking areas we are carrying on one of the most interesting demonstrations of real health work anywhere in the world, getting the co-operation of the priests who urge people to go to health centres. In the city of Montreal there are two institutions we have had the pleasure of co-operating with-the McGill University with its medical school and the University of Montreal which has a medical school which is most promising and represents an excellent type of medical education. We come to Toronto. I do not want to give you undue pride of your own importance. (Laughter.) That would be supererogation. (Laughter.) The people who come here to visit the combination you have here go away saying, “This on the whole is unique.” Here you have a university medical school working in close co-operation with a university school of public health, and working in close co-operation with an extremely efficient and finely organized city department of public health whose honourable head is here. You have the whole working with a broad-minded, forward-looking Provincial Department of Public Health. You have one of the finest systems of public health to be found anywhere in the world. I congratulate you with all my heart on a combination so good that we send to Toronto almost all of the nurses and Fellows that we bring from other countries, because they get more here in a smaller compass and a shorter time than anywhere else.

Then on to Alberta where there was an opportunity to do something for a very progressive and alert medical school. To British Columbia and now across the Atlantic to Hong Kong where it has been a very great privilege to endow three professorships. At Singapore the King Edward VII Medical School is a great credit to British science in the far east. Then Ceylon to India in many parts of which we have been co-operating with the public health authorities. A recent development was a very substantial contribution to public health in connection with the University of Calcutta. We pass on to Egypt and Jamaica where important work is being carried on.

I must refer to yellow fever which has been prevalent in Lagos on the West coast of Africa. In mentioning yellow fever I want to pay tribute to the memory of Adrian Stokes, an Irish bacteriologist, a splendid personality and sportsman who went down with yellow fever in some mysterious way. As soon as the disease was diagnosed, he called for experiments to be made on his own body. He asked that his blood might be transferred to monkeys in order that the complications of his case might be studied. As long as consciousness lasted he talked about scientific problems. That represents sportsmanship of the highest level in human contact. (Applause.) Another Englishman, Dr. Young, who supervised work on the west coast of Africa came down with the infection which proved fatal in a few days. If it were permissible to disclose intimate records I could read letters from mother and widow to Dr. Young. What splendid courage these English women have. In all their sorrow they displayed that pride in his ideals and in the glorious death he died.

You see the sweep of this work done round the British Empire. Nearly a thousand Fellows are being maintained at the present time at an expense of nearly two million dollars-by funds from the Rockefeller Foundation. Nearly all of them are subjects of the British Empire, going from one country to another to carry on researches. Why is this being done? It is not being done with the hope of gratitude. Anybody who works for gratitude is going to be disappointed. Anybody who works from the desire to accumulate gratitude is working from a wrong motive, and deserves what he gets. We are doing nothing except the most selfish thing in the world. We are interested in promoting public health and science. We are selfish about it. We exploit anyone who will help us. It is purely a selfish thing. (Laughter.) The question of gratitude should not be considered. Your chairman most graciously alluded to understanding and goodwill. We are not working for understanding and goodwill. We have no fault to find with people who set out to promote goodwill. We have a theory that you do not promote goodwill by going straight after it. We feel if the peace of the world can survive the societies promoting peace and goodwill, it will be one of the marvellous phenomena of the time. It is like culture. You cannot put salt on culture’s tail. The thing to do is to try and live a large rich life. The most cultured people in the world are the people who do not know they have it. I believe the same thing applies to international relations. Some think if you can get people together you are going to make them love each other. I need not tell them that tourist traffic is one of the dangers of international relations. People who get home remember how they got poor food and how the taxi driver overcharged them. These people do not know a great deal about promoting understanding and goodwill. What is the way? Work at some great task? The world is never going to be patched together. I have not said a word about that three thousand miles of boundary. (Laughter.) We have ever-worked that. Why not guns and ships? For the obvious reason, we have common interests. Lately there has been a little uncertainty about the boundary. (Laughter.) It has been fortified in other ways. (Laughter.) There is the other idea I have not said anything about hands across the sea for a long time because an Englishman said, “yes feeling for our pockets.” (Laughter.) I am even afraid of saying anything about blood being thicker than water in case someone talks about blood suckers. (Laughter.) It has been a stimulating and stirring experience to meet all the fine men and women around the world and in the British Empire with whom we have been brought into contact. It has been a most gratifying and delightful experience and one which has given the greatest satisfaction to co-operate with the Empire at home and in the Dominions and Colonies in helping to build up great causes whose significance and influence spread beyond national borders and are a real contribution to that thing we call the civilization of the world which all of us have a little sneaking, lingering hope can be promoted more and more with better feeling and less animosity because people have discovered common interests and are bound together by sane genuine sentiment which is different to sentimentality-which is characteristic of those who work for common causes shoulder to shoulder, losing their self-consciousness in the great overwhelming sense of achievement in a glorious common undertaking. I have heard that an optimist is a person who sees an opportunity in every difficulty and a pessimist is one who sees difficulty in every opportunity. Let us be in a true genuine sense optimists,-in a sense that there may be difficulties-that these difficulties can be patiently and quickly turned into opportunities of better co-operation which may help to patch together this distracted old planet of ours. (Applause.)

DR. VINCENT was cordially thanked on behalf of the Club.