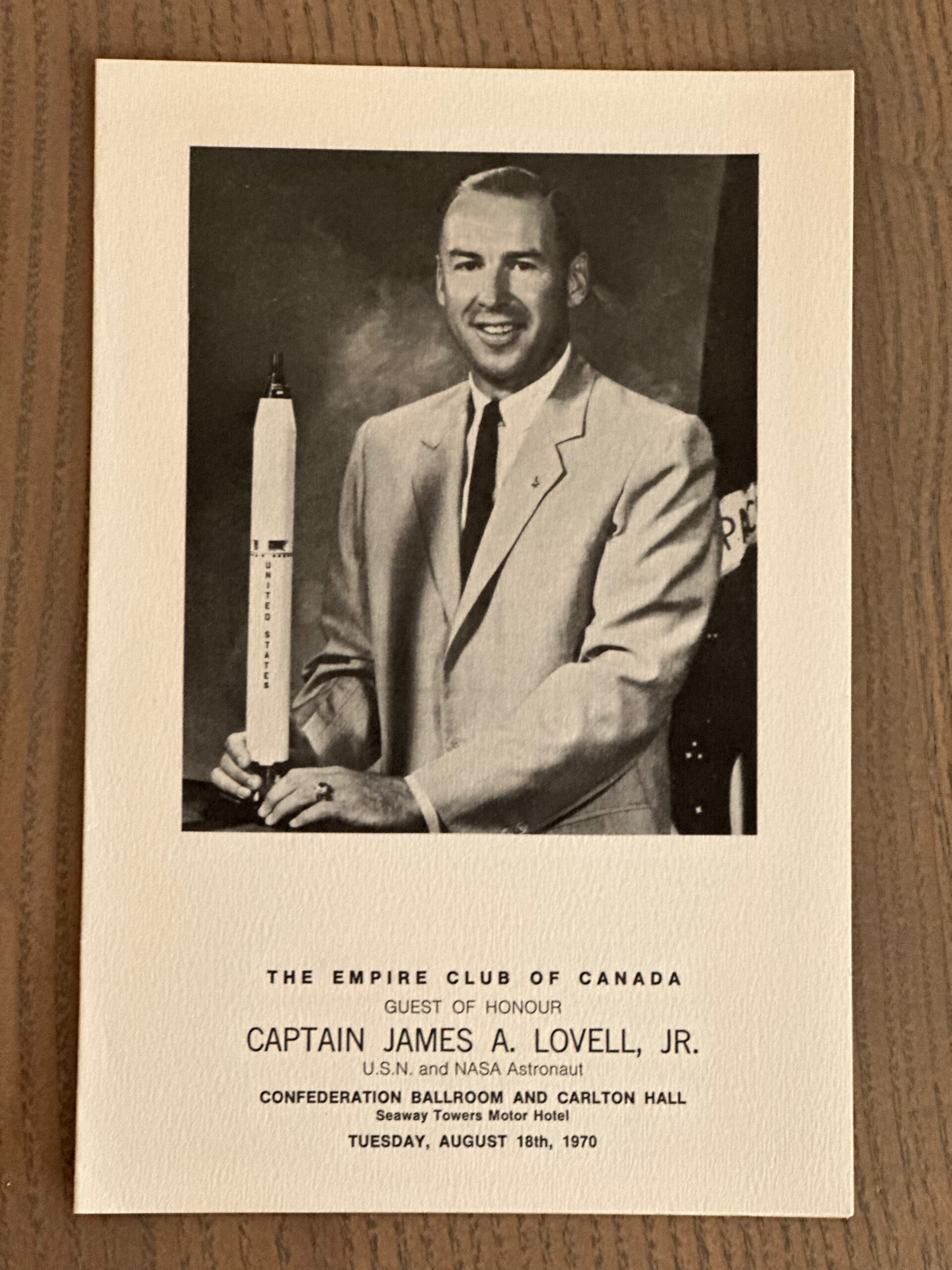

The Apollo XIII Mission

AN ADDRESS BY Captain James A. Lovell Jr., COMMANDER APOLLO XIII

CHAIRMAN The President, Harold V. Cranfield

GRACE The Rt. Rev. F. H. Wilkinson, M.M., E.D.

DR. CRANFIELD:

"Ladies and gentlemen, I ask you to remain standing for the entrance of the Vice Regal party and for what is to follow. The Royal Salute will be played when his honour the Lieutenant Governor has reached the place where I am standing now. Grace will then be said by The Right Reverend F. H. Wilkinson. After which we will sing one verse of ‘O Canada’ and we will then have two toasts. The first to her Gracious Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second; following which we will toast The President of the United States of America and only then may we take our places."

After Grace, said by The Right Reverend Bishop Wilkinson, the toasts were given and dinner followed.

After dinner the Chairman presented the Head Table Guests. The President introduced from the audience one of the Empire Club’s most remarkable members. (He is Mr. H. H. Sutherland, 102 years old and still going to business every day.)

DR. CRANFIELD:

Now ladies and gentlemen, it is my pleasure to present to you the Honourable W. Ross Macdonald, P.C., C.D., Q.C., LL.D., the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario and we are proud to say the Honorary Vice President of the Empire Club of Canada. His honour brings greetings from our Queen. Sir

The Lieutenant Governor made his gracious presentation on behalf of the Queen.

Please convey our loyal appreciation and our thanks to her.

We are breaking with the traditions of the Empire Club because of the generosity of our speaker. He has volunteered to give answers to your questions at the end of his address. There are pads of paper on each table in this room. Will you, as the evening progresses, prepare your questions? They will be collected by the gentlemen with the red boutonnieres, who are our Reception Committee and these will be brought up by them to Mr. Ian Macdonald. Those considered as having the most bearing on the topic and which have not been answered in the address itself will be dealt with as full as ten minutes time will allow.

Mr. Ian Macdonald is the man by whose energy and persuasion our guest became available. We owe the delight and pleasure of having our distinguished guest here to address us because of Mr. Macdonald and he will present him to you now.

MR. MACDONALD:

It was nearly five hundred years ago that Christopher Columbus reported: "I undertook a new voyage to a new Heaven and World." Let us, then, imagine that we are gathered this evening in a fine banquet hall in the capital of Spain, during that earlier age of discovery. Throughout the feast, an atmosphere of expectation permeates the room while a sense of awe and wonder is evident in every conversation. And now, amidst the flickering candlelight, a hush descends on the guests and the great explorer, Christopher Columbus, rises to his feet to be greeted and acclaimed by those present. Ladies and Gentlemen, at this moment, we become those same people, but of this century, of this age, and in this year, all sharing the privilege of a great moment. For who can doubt that our guest today has a place among the legendary explorers of all time.

In recent months, we have been exposed to the pronouncements of various skeptics, to the near vision of the astigmatic, and to the opinions of those who suggest that the space programme is either wasteful or misguided. Of them, it must be asked: can we ever truly afford to diminish the thirst for knowledge or to foreclose on any frontier that still imposes a challenge to mankind? It was Tennyson who wrote of the classical Ulysses, yearning "to follow knowledge like a sinking star, beyond the utmost bound of human thought." Of course, prejudice dies hard. The members of the "Flat Earth Society" remain unrepentant and unchanged in their faith and its affirmation!

Among those same critics are some who hold the view that astronauts are no more than highly skilled technicians, programmed as mere ciphers in a complex computer equation, although, Sir, no one has ever been able to argue that they are highly paid. However, could anyone who watched Neil Armstrong make a split second decision to put the lunar module down on the moon, at the virtual point of fuel termination, and then execute the final landing on the basis of personal machine correction, doubt that unusual skill and courage were required? Did not the countless series of perilous risks, which Captain James Lovell was called upon to assess during the return of Appollo 13, require the highest order of human judgment and determination?

Through the magic of electronic communications and instant exposure to history in the making, it was possible for each one of us to be present on those voyages and to share in the discoveries of the moment. So much is the Astronaut a modern everyman that we have difficulty even imagining the complexity of his task. Indeed, it would appear that most astronauts are themselves completely free of illusions of grandeur. Returning from the epic voyage of Apollo 8 in December, 1968, Captain Lovell received a thunderous welcome in Houston at 2.00 a.m. Commenting later, he mused: "I was rather surprised by the great reception committee; I had really just expected to tumble into my old Chev and drive home and go to bed."

But then, our guest this evening has felt close to space for a very long time indeed. It is reported that, as a youngster in Milwaukee, he frightened some of his skeptical neighbours by firing a homemade rocket 80 feet into the air. He wrote a thesis on rocketry, while a Midshipman at the Naval Academy and, it is alleged, he sent it to his high school sweetheart to have typed. She, in turn, must have injected some moon magic into the document, because they were married on his graduation from the Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1952. He has been flying high ever since!

He immediately proceeded to flight training as a Navy Captain, and undertook numerous naval aviator assignments, including a four-year tour as a test pilot at the Naval Air Test Center in Maryland. He has also been a flight instructor and safety engineer, recording 4400 hours of flying time, including more than 3,000 hours in jet aircraft prior to flying a NASA T-38 from Houston this morning. However, his devotion to rocketry, in which he had retained a creative interest during his formal education, was finally rewarded when he was selected as a NASA Astronaut in September 1962. The remarkable story of his participation and recognition is recorded in the printed programme at your tables this evening. What more is there that one can say about a man who has undertaken more space flights than any other person, and holds the Astronaut record for time in space at 670 hours? Those of you who saw the Gemini capsule at Expo 67 would have reason to contemplate just how confining it can be to spend two weeks in space, as Captain Lovell did in December 1965.

Although the spine-chilling excitement of Apollo 13 is hard to surpass, it was the voyage of Apollo 8 which will always, for me, be one of the most moving experiences of our time. Recall, if you will, that journey into the universe, and the awesome moment when man first disappeared behind the far side of the moon, totally out of contact and communication with this planet. That voyage took on added significance through its coincidence with the Christmas season and its message of new life. On such a journey, I suspect that you, Sir, were in a position to contemplate the juxtaposition of science and religion as few men have been privileged to do, and to understand why man’s venture into space should help us, in the words of Archibald McLeish, "to see ourselves as riders on the earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold–brothers who know now they are truly brothers."

I first had the pleasure of meeting James Lovell at a dinner party in Toronto in 1967 and, tonight, a long-lasting hope that he might accept an invitation to the Empire Club has been realized. If you will forgive a reference to your own remarks, Sir, I was struck by two comments which you made, at that time, related to the perspective provided by the experience of sailing through space. One was to look down on a tiny corner of the world–the Middle East, for example and to reflect how unnecessary it seemed that people could not live, side by side, in peace rather than in conflict. The other was to stand apart from the earth and see it fully, not as an end in itself, but as part of a total constellation of bodies which make up the universe. Who, you asked, could fail to recognize that there must be some higher power which binds the system together?

Ladies and Gentlemen, when the Admiral of France was briefing his captains before the battle of Trafalgar, he said: "Let there be no ignominious manoeuvring. Any captain who is not under fire is not at his post." Captain Lovell is one who was under fire in as exacting a manner as any man could be during the hazardous flight of Apollo 13. It was, indeed, a case of brilliant manoeuvring under constant fire.

James Lovell is asked regularly whether he would like to go to the moon again. I would suggest that the answer is to be found in his statement, describing the experiences of December 1968. He said: "The lunar surface was so close, it beckoned. I felt that if we could only get that scant 60 miles closer, if we could only get beneath the dust of the centuries, we would have a chance to pry open some of the secrets of creation." For the poet Edgar Alan Poe:

Sir, I suspect the moon never beams without bringing you dreams, nor the planets ever glow without itching your toe.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I am proud to present a unique traveller in space, a down-to-earth ambassador, and an engaging human being–Captain James Lovell.

CAPTAIN JAMES LOVELL:

Thank you, Mr. Macdonald, for those wonderful remarks.

Distinguished Members of the Empire Club, families, guests, I am honoured and proud to speak on Canadian soil. As I understand, this Club has been in existence almost back to the beginning of the century, and it is a pleasure for me to be one of the honoured speakers here.

I am also proud to be here because, as many of you know, I have a Canadian background. My father was Canadian, and I have in fact right over here at this table many of my Canadian relatives with me. So it gives me a double pleasure to be back in Toronto to welcome you all and to see my friends and relatives again.

We at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration have long valued our friendship with our Canadian neighbours and your most helpful co-operation in our space programme.

Even now some of your scientists are examining moon rocks that were brought back on the successful Apollo XI and XII missions. For our part we are proud to be able to share our ideas, our experience, and our newly acquired knowledge with your country as well as all nations of the world.

Canada, by the way, was well represented on that first historic mission to the moon.

You may recall that when Ego, the lunar landing craft, put down on the lunar surface on July 20th, it did so on Canadianmade legs. I have heard that Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin said they had seen no legs on earth that appeared more beautiful than those. And I can imagine that time that they were very truthful sayings since they were the thing that depended on their getting back home again.

I hope that we can continue to work with you in the space effort.

The purpose of United States space programme, as I am sure all of you know, is to bring its benefits for the peaceful uses of all mankind; the kind of peaceful co-operation that has existed for generations between your country and mine.

We look now at a very different world from the one in my youth or even of a decade ago. We must learn to look upon the strange ocean of space not as a fearsome danger upon which voyagers may not return, but as a medium in which our spaceships can pass back the riches of new knowledge.

Young people of this decade can look forward to altogether fresh opportunities that no generation before was given to test their minds, their skills and their hearts, and increase their vision in the human role in the scheme of things. They will learn the new sciences of space and become familiar with new cosmology knowledge to frame their concept and gain a new view of man and his destiny.

For the first time they will perceive the earth as a psysical whole whose horizon is the unlimited vastness of space instead of trying to reform and reshape man to conform to an abstract ideal. They can focus on restoring and reforming a favourable environment in which man of diverse talents can contribute to human progress, an objective that advancement of technology makes feasible.

More and more we are going to have to rely on the power of the intellect and the heart to navigate our way in this new world that the space age now in its second decade has opened.

Our excursions into space offer valuable lessons. Space flights such as the Apollo missions, for example, teach us the value of constant concern over minute details as well as regard for broad objectives. We have learned, too, that true wealth is harnessed energy placed in the service of mankind.

We are now witnessing the birth of a new man, the man of the universe, whose ties remain with the mother earth.

Science and technology have played key roles in this particular birth, and the reason for this is we could not navigate our way through the ocean of problems and obstacles to achieve man’s broad objectives without the aid of instruments and tools and vehicles required for the journey. So this is another lesson we are learning in space flights, both in manned and unmanned space craft. What we can see is only one per cent of reality. Ninety-nine per cent of the electromagnetic spectrum is invisible, and much of this not only is invisible but cannot be sensed except by instruments designed for that purpose.

When we realize that the earth’s environment is directly and vitally affected by radiation and particles from outer space, that we require precise measurements of the energy poured out by the sun into this environment in order to understand the mechanism of this dramatic reaction, we shall begin to appreciate the importance of instruments and human intellects which devised them.

Science and technology are the keys to man’s survival and well being, but they must be guided by man’s compassion for his fellow man, and indeed, for his fellow creatures.

Many of our urgent problems today are global in nature. As one who has viewed the earth from the distance and the prospective of space, I was impressed by its uniqueness in our solar system and its vulnerability. It is the habitat of all mankind, and we are in all likelihood unique; the only such life form in our solar system.

Global unity is, therefore, the most striking characteristic of earth as viewed from space. We see its cloud systems encircling our world; their beauty is startling against the great void in which it exists that no artificial barriers of national boundaries can be seen. The land areas are bounded only by the seas and the oceans, and together with the atmosphere and sun, interact as an ecological unit. Our life has achieved on a vast scale what man is striving to achieve in a tiny space craft: a closed cycle life-support system.

If we are to maintain the earth as a livable dwelling place for mankind, we must learn to view it as a whole, we must understand that our existence depends upon the delicate balance of nature, and that this balance includes not only all of mankind, but all of living things. We must know the intricate relationships and inter-actions between planet earth and a dynamic solar system, particularly the sun.

To obtain this knowledge and understand it requires a sustained programme to develop the science technology necessary to reveal what man’s limited senses and capabilities cannot reveal unaided.

We are concerned today with the threat of pollution to our environment. We have become more keenly aware of environmental pollution from the view we have from space as observed from manned and unmanned space craft.

Our preliminary observations made as early as the Mercury orbits in 1962 and the earlier Tyros weather satellites lead us to the concept of instrumented space craft capable of locating and monitoring the earth’s resources.

The growth of the world’s population and its attendant demands for food, potable water, shelter, transportation, communications, means that all nations ultimately must join in managing the use and replenishment of our natural resources.

Expanding population also poses its own pollution and waste problems by overburdening the natural ability of the ecological system to absorb them without disturbing its balance.

In both instances the space programme offers capabilities directly aiding in the solution of these problems by means of instrumented space craft that can identify and monitor resources and pollution on a global basis.

The space programme has taught us many things about our environment, but serious gaps of essential knowledge remain. For example, we have no idea how stable our present climate is, or how much additional atmospheric pollution can be tolerated without drastically altering it.

Such knowledge comes to us in many ways: from sensors in space craft orbiting the earth, from space probes investigating the atmosphere of Mars and Venus; from observations and photographs made by astronauts, and from the analysis of extraterrestrial material brought back from space missions to the moon.

We already know that Mars and Venus have atmospheres and environment quite different from the earth’s and from each other. (If) we understand why they are so different, what processes caused them to evolve along different lines and what processes control the temperatures and composition of atmospheres, then we may better understand and manage the earth’s atmosphere.

Analysis of the solar wind content of the lunar rocks and dust, for example, may give scientists a measure of the sun’s activities through eons of time. This could reveal the causes of past climatic changes on earth that resulted in the ice ages or extended periods of tropical climate.

By using a Laser reflector on the moon the wobble of the earth about its axis may be accurately measured and scientists may thereby be able to forecast earthquakes, for it is suspected that the wobble causes stresses in the earth causing and resulting in these quakes.

Thus one of the immediate challenges to the National Aeronautic and Space Administration if we are to help in solving the problems of the earth ecological balance and conservation of its resources is to determine the kind of space systems needed.

If we are to solve the earth’s problems of the conservation of resources, we have to determine the kind of space systems that are needed, and to develop them for these purposes.

In addition to the scientific spacecraft that gathered data for a basic research, the Space agency plans to orbit the earth resources technology satellite system in 1972. This will be designed to send us data on farming, forestry, the oceans, fresh water sources, geological formation and land use, and a lot of this, of course, is very much of interest to the people in Canada.

They will give us a more comprehensive view of the dirty air and polluted waterways around the globe than could be obtained by any other means within the same time period.

The first of these satellites will be launched into Polar orbit so that they can scan the entire globe as it turns underneath.

By means of the instruments and special cameras, the satellites will measure and capture on infrared film the invisible radiations from plants and trees and the earth’s surface features. Experiments have shown that each object or material has its own special radiation called a spectro image that identifies it, something like finger prints identify a person. By making the spectro images, the technicians can identify the farmer’s crops and the trees in the forest, and can even determine whether they are healthy or diseased or require more moisture. It seems the healthy plants and trees show up in the infrared film literally in the pink, while the diseased ones appear a nice blue-green.

When such satellites are operational, an inventory of crops and forests can be maintained and their state of health and maturing monitored, making for better crop and forest resource management.

Forest rangers also are interested in the ability to detect fires that start in remote areas, and hydrologists have an interest in locating fresh water sources.

Also remote sensing from space seems to be the only feasible way to monitor oceans, covering surface temperatures, sea states, currents, and marine biology, all information that is of course vital to shipping and the fishing industry.

There is much more, but it would take much too long to describe here. Yet the benefits to the world of such a satellite system can be appreciated when we consider its application to the problem of feeding our fast-growing population.

A satellite that can identify and monitor crops as they mature and reach the time for harvesting will help not only in management, but in pest control, and thus add substantially to our food resources. Information on these aspects alone will be worth a great deal, not only to the United States but to all other countries desiring this information.

Perhaps from these examples you can begin to see that the space programme is creative. It contributes new scientific knowledge, new concepts of the earth and the universe; new techniques and technology to help us solve our problems on earth.

One of the important contributions is that the space programme has accelerated the trend by which we can accomplish more with visibly less material. For instance, one of our one-quarter ton communication satellites outperforms trans-oceanic cables that weigh some one hundred and fifty thousand tons. The most advanced trans-oceanic cable now being developed, but not yet in service, has 720 channels.

Today now in service Intel-fat system of the International Telecommunications satellite consortium–provides more than 3,000 channels, and a new satellite system scheduled for service next year will have 6,000 two-way circuits.

This provides some idea of how by advancing technology through scientific research we can conserve precious resources and at the same time serve mankind better.

United States Space Agency has demonstrated a unique blend of governmental, industrial and academic research competence and achievement. Without changing our political system we have shown how to forge these dynamic elements together in new ways, building an effective team, that has released creative talents of hundreds of thousands of people.

Advances required in every technical discipline by NASA in order to build the Apollo lunar landing system its permanent knowledge; not transient. Once you know how to do something, that knowledge can be used over and over again in as many fields as there are engineers.

In turn, this leads to other advances in related technologies; a steady hand-over-hand technological progress.

The space programme not only creates wealth by teaching us how to harness enormous energies, it also stimulates the economy indirectly.

A good example is the computer industry. Exploration of space demands that we have large computer systems of great complexity and speed. More importantly, it requires flexibility in the use of computers. This ranges from automating check-out of rocket systems, to real time monitoring of space missions, from inventory management to spacecraft simulator controls, from computer planetary trajectories to modelling global weather patterns.

The NASA complex of more than six hundred computers is one of the world’s largest automatic data processing systems. Without these systems there would have been no Apollos, no Mars fly-bys, no weather satellites with their automatic read-out systems or other space missions flown successfully.

It would have been impossible to have brought back Apollo XIII last April without the help of these extraordinary machines and their talented operators. NASA could not have developed the advanced management techniques that are being adopted in business and industry that we have made possible, the management of large diverse activities.

The U.S. computer industry, largely as a result of the requirements of the space program in general, and Apollo in particular, now does about eight billion dollars worth of business a year; pays the highest average wages of any American industry, and is one of the fastest growing.

In looking at space at a different prospective I believe our space programme has contributed both emotionally and concretely to a new sense of a common human identity by people all over the world.

The many hundreds of millions of people were there with Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong when they first stepped on the moon, and shared the experience of a great triumph, not just for two men but for all mankind, as Neil stated. Those who watched became in that moment not just Americans or Europeans or Asiatics or Africans, but members of a great brotherhood with a common interest and a common humanity.

Neil and Buzz were not just Americans up there on the moon. They were representatives of all mankind, the first to set foot on another world. It was that spirit that they left behind with them a memorial which read: "We came in peace for all mankind."

How does one evaluate this achievement of the space programme? That moment when so many hundreds of millions of people simultaneously realized their common humanity, and again on Apollo XIII during the long hours when Fred Hayes and Jack Sweigert and I were aboard our crippled spacecraft as it returned to our home planet, twelve nations, including Russia, offered all possible help for our recovery. From nearly every country came prayers and words of encouragement.

Finally, a futuristic view of our space efforts brings forth this thought: with conditions here on earth crowding us, the ultimate major benefit of space may be the liberation of the human being. Once more man will be able to travel to far away places. Once more he can live as he lived in prehistoric times, enjoying individual freedoms, unhampered by bureaucracy, pollution and other encumbrances under which he now labours.

Once more humanity will be able to congregate in small units, instead of small cities. Once more man will be master of his world.

We can shape our own destiny for space gives off an insight into the world of tomorrow. We can get away from wars and isolationism and over-population. We can close the door on the threat to the type of life we like to live and go one of adventure if we try, and I predict some day we will try.

Our flights to the moon have demonstrated that men of goodwill can work together to achieve almost impossible goals. That being the case, the last quarter of this century should be an age of exploration such as man has never seen before.

Against the immense backgrounds of our vast solar system, itself a microcosm of an infinitely vast universe, we look upon man as exceedingly small, yet he is endowed with a divine spirit and imagination that will carry him to a greater understanding of his creation.

DR. CRANFIELD:

We will postpone our expression of thanks until after the question period.

(The audience had been invited to prepare questions in writing. These had been collected and with editorial assistance these were presented as follows and answered by Captain James Lovell.)

THE QUESTION PERIOD

E.C.: The first question is one from a young man, age nineteen: I have endeavoured in many conversations to find out why the United States is spending so much on a space programme instead of devoting its capital to the sadly lacking poverty program in your country. (Here is a fellow who hits right from the shoulder.) If you insist on saying that the programme has contributed much to the scientific and technological fields, please give some examples that can be associated with everyday life besides space food sticks.

Captain Lovell: I think that during my talk I did mention some of the benefits a programme had in company with other programmes. I would like to leave this one thought with you, though: in the total time that we had a space programme in the United States we spent, up through the landing on the moon, a total of thirty-five billion dollars. That is for the entire ten or eleven years.

Last year, our country spent on poverty correction (one year) thirty-seven billion dollars.

Now I am all for elimination of poverty, but I rather feel I would like to see some positive achievement sometime, and I think our programme has done that.

E.C.: Here is one from the distaff side. It says: Do you think women are capable of handling a space mission?

Captain Lovell: Noting the number of talented women there are in the audience I would say they certainly are.

E.C.: How soon do you feel that science astronauts might be able to join lunar landing missions?

Captain Lovell: We have people who are called scientists astronauts. Actually we all are a sort of scientist astronaut. We started out as test pilots and became scientifically developed through our years with NASA in certain fields; mostly geology.

Scientists that are now on board, whose basic science is geology, will be on our lunar missions. The other scientists such as physicists, doctors, astronomers, are being trained now for earth orbital missions, either for earth resources or for study in the heavens, and our first one of those missions will be a sky-lab which we hope to launch in 1972.

E.C.: What were your thoughts when you found that the mission had to be aborted?

Captain Lovell: My first thought was, of course, one of disappointment. Fred Hayes looked at me and said, "When we lost our one fuel cell and the oxygen tank our mission rules had stated we could not now make the landing." We did not think it was as serious as it was until we lost the other two fuel cells and the other oxygen tank. And then the thoughts of landing had completely left our minds, and it was thoughts of landing back on earth that were most important.

E.C.: On the subject of pollution, on a news broadcast this evening reference was made to the age-old laws of conservation of weight and matter. By taking matter and weight to the moon and in fact returning with both, has this law been disproved?

Captain Lovell: I am going to wait until you have one of the scientist astronauts–he will speak to you.

E.C.: There is a quotation from the top of the menu which brings to mind: Does one feel there is a Supreme Being while up there? Why is this so?

Captain Lovell: The ability to make one of these lunar voyages gives one a prospective that is not easily obtained in other means. I feel that I