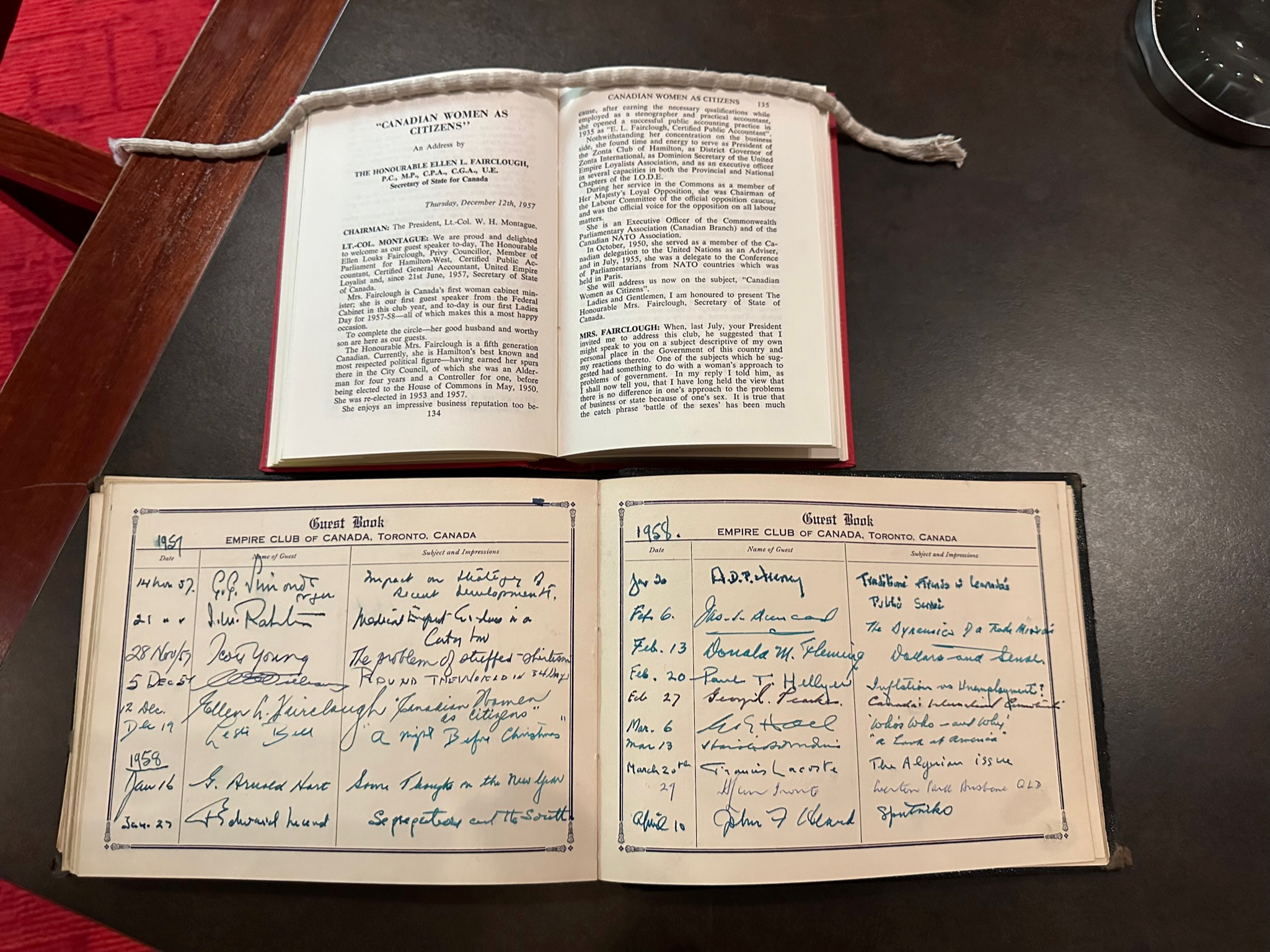

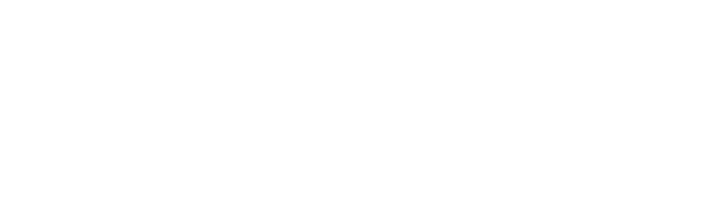

An Address by THE HONOURABLE ELLEN L. FAIRCLOUGH, P.C., M.P., C.P.A., C.G.A., U.E. Secretary of State for Canada

Thursday, December 12th, 1957

CHAIRMAN: The President, Lt.-Col. W. H. Montague.

LT.-COL. MONTAGUE: We are proud and delighted to welcome as our guest speaker today, The Honourable Ellen Louks Fairclough, Privy Councillor, Member of Parliament for Hamilton-West, Certified Public Accountant, Certified General Accountant, United Empire Loyalist and, since 21st June, 1957, Secretary of State of Canada.

Mrs. Fairclough is Canada’s first woman cabinet minister; she is our first guest speaker from the Federal Cabinet in this club year, and today is our first Ladies Day for 1957-58–all of which makes this a most happy occasion.

To complete the circle–her good husband and worthy son are here as our guests.

The Honourable Mrs. Fairclough is a fifth generation Canadian. Currently, she is Hamilton’s best known and most respected political figure–having earned her spurs there in the City Council, of which she was an Alderman for four years and a Controller for one, before being elected to the House of Commons in May, 1950. She was re-elected in 1953 and 1957.

She enjoys an impressive business reputation too because, after earning the necessary qualifications while employed as a stenographer and practical accountant, she opened a successful public accounting practice in 1935 as “E. L. Fairclough, Certified Public Accountant”.

Nothwithstanding her concentration on the business side, she found time and energy to serve as President of the Zonta Club of Hamilton, as District Governor of Zonta International, as Dominion Secretary of the United Empire Loyalists Association, and as an executive officer in several capacities in both the Provincial and National Chapters of the I.O.D.E.

During her service in the Commons as a member of Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition, she was Chairman of the Labour Committee of the official opposition caucus, and was the official voice for the opposition on all labour matters.

She is an Executive Officer of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (Canadian Branch) and of the Canadian NATO Association.

In October, 1950, she served as a member of the Canadian delegation to the United Nations as an Adviser, and in July, 1955, she was a delegate to the Conference of Parliamentarians from NATO countries which was held in Paris.

She will address us now on the subject, “Canadian Women as Citizens”.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I am honoured to present The Honourable Mrs. Fairclough, Secretary of State of Canada.

MRS. FAIRCLOUGH: When, last July, your President invited me to address this club, he suggested that I might speak to you on a subject descriptive of my own personal place in the Government of this country and my reactions thereto. One of the subjects which he suggested had something to do with a woman’s approach to problems of government. In my reply I told him, as I shall now tell you, that I have long held the view that there is no difference in one’s approach to the problems of business or state because of one’s sex. It is true that the catch phrase `battle of the sexes’ has been much quoted for many years. So it is probably appropriate that I should quote an unknown source which said:

“The battle of the sexes will never be won by either side.

There is too much fraternizing with the enemy.”

However, battle or no battle, there is no doubt that a woman’s role in society today is vastly different from what it was at the beginning of this century. Accordingly, it seemed to me that it might be a good opportunity to speak to you on the subject of `Canadian Women as Citizens’, and if you take issue with any of the things which I shall say to you today, I hope you will bear in mind that I do this at the invitation of your President. Since he also comes from Hamilton, where we have a reputation for winning tough battles, I am sure he will emerge victorious from any barrage to which he may be subjected.

From time immemorial women have played a part in public affairs, sometimes greater, sometimes lesser, sometimes for good and sometimes for evil. Names which come down to us through history have been immortalized in song and story, in poetry and in drama. But in order to paint a picture to serve as background for the events of the last half-century and the situation in which we find ourselves today, I must go back for a moment to three hundred years and more ago, to the days of the early settlers when white women first came to this continent. To the courage of those women we must all pay tribute. They came in many capacities. Some to join husbands who were already here; some came as domestics; some came as poor relations to act as unpaid domestics; and some came to be the wives of men they had never seen.

These early women worked side by side with their men, clearing the land, planting the crops and even, on occasion, shouldering the musket to defend their families and their very lives against hostile forces.

In addition they fed their families; they doctored and nursed the sick and the aged; they spun and wove and clothed their families; and they were forced to make with their own hands and by means of their own ingenuity whatever articles they needed for their households-candles and soap, garments and furs, and the medicines with which to treat the various diseases and ailments which assailed them. The pioneer woman was the original welfare worker on a voluntary basis. Versatile she was in the extreme and if her daughters have imparted to their daughters, in turn, the gift of adaptability, they should be proud to accept a prize so richly won and so much a part of their heritage.

Things were not too easy for women in the new world, but then, of course, they were not very easy for men either. This situation existed for a long, long time. As a matter of fact, if we take a look at the beginning of this century, we can see some very interesting things. A mere handful of women were in business and those who were, were usually in family businesses which they had built up themselves or which they had inherited. The main means of earning a livelihood which was open to women was domestic work. There were a few clerks in stores and there were openings for women in the needle trades. Unless a woman engaged in one of these activities, she either married or became an unpaid domestic or social secretary in the home of one or other of her relatives.

It had only been a short time before the turn of the century that universities in Canada had opened their doors to women. The first one to do so was the University of Mount Allison College at Sackville, New Brunswick, which signified its willingness to accept women in 1873. The first woman in Canada to be given a university degree was a graduate of this university in 1882. Dalhousie University at Halifax admitted women in 1881 and the University of Toronto in 1883. The following year the Arts course at McGill University was opened to women.

A short time ago, a friend sent me a clipping from the Hamilton Spectator of March 16th, 1900, in which is described a sermon delivered by a Doctor Talmadge in Washington, D.C., in which that reverend gentleman drew to the attention of his hearers the terrible conditions under which women were seeking to support themselves. He painted a pitiful picture of work in the needle trades which I shall not attempt to recount for you here today, but I think that it is worthy of note that a common wage was $2 or $3 a week and many were trying to exist on a piecework basis at rates which brought them only about 25 cents a day. Incidentally, on the other side of this clipping, I found advertisements for three Hamilton department stores of the time and some of the prices quoted are extremely interesting. I see that a well-known dry-goods store of that time was advertising a full range of spring coats for $4, and in order to entice trade into their establishment, they were advertising five shows on Saturday: 10:30, 2:00, 3:15, 4:30 and 7:15. The advertisement goes on to say that “a purchase of 15 cents worth of goods admits you to an entertainment a good deal better than you expect.” Other things I notice in this advertisement are ladies’ Irish linen handkerchiefs for 7 cents, men’s fleeced and all wool shirts at 35 cents, infants’ vests at 5 cents, men’s hose at 27 cents and a great many other intriguing items.

There were several events which brought women to a realization of their responsibilities as citizens during this half-century. The First World War brought women out of their homes to work in industry and commerce, taking the places of the men who had joined the armed forces. The Second World War brought them out in still greater numbers and this second time, there was evident reluctance to return to domestic duties. By the end of World War II, of course, living conditions had changed. Our grandmothers in the early years of the century did not enjoy the vacuum cleaners and automatic washers and the refrigerators which lighten home tasks today. Instead, as many as two or three women may have had to spend time keeping one home functioning, whether as mother, maid or unmarried relative helping with daily chores. Now, all of these women are to some degree released by mechanical advances and by an improved living standard for work outside the home. Women now have time to work full-time or part-time in the world of business, politics or community affairs.

It is hard to say which came first, the chicken or the egg. Did these appliances come into being because of the demand of women who were doing two jobs during the First World War, and did their acceptance steadily increase in the intervening years; or did women, because of these appliances, find that it was possible for them to spend more and more time away from their domestic chores? Whatever the reason, the acceptance of women as workers has altered our whole scheme of living–to the extent that now, in place of the large family home served by several women, we have the comparatively small functional establishment which is quite easily handled by one woman, even on a part-time basis.

We can see the extent to which women have become free for new responsibilities by the fact that the number of women in gainful occupations in Canada multiplied almost five times in the half-century from 1901 to 1951. The number of working women increased from 238,000 to 1,147,000, and the proportion to every 1000 males gainfully employed rose from 154 to 282. Women in clerical occupations increased about 25 times from 12,600 to 314,600.

A recent Dominion Bureau of Statistics report points out that altogether 22.4 per cent of employees in Canadian industries are women (Latest Labour Digest 24.6%). In some industries, there are nearly as many women as men. In the service industries–mainly hotels, restaurants, laundries and recreational facilities–women constitute 46.8 per cent of the employees. In finance, insurance and real estate, 51.3 per cent of all employees are women. The proportion of women in industry is highest in Prince Edward Island (24.8 per cent), followed closely by Ontario (24.1 per cent). Of all major Canadian cities, Kitchener, Ontario, has the highest percentage of women employees (31.5 per cent).

Women are prominent in many professions which were once a masculine preserve. In science and engineering, women biologists and chemists are particularly numerous, but there are geologists, physicists, electrical engineers and aeronautical engineers as well.

In seeking employment, women encounter some of the same problems as men. Women are living longer, and increasing numbers of mature women want or need gainful work. Actually, 19.4 per cent of all women in Canada who are from 45 to 64 years of age are working for pay and 4.1 per cent of those who are 65 and over. Older women in many instances face the same problem as older men in obtaining new jobs. A man who is 45 years old may find potential employers prejudiced against him on account of his age. The older woman encounters the same difficulty. But for women the point of prejudice–more often begins at the age of 35.

As women accepted more responsibility in industry and commerce, they naturally sought a voice in government. It was not until 1921 that the franchise was extended to women in Canada on a full basis. It has always been amusing to me that the type of thinking which could condone the Boston Tea Party and the War for Independence could refuse to extend the right of the franchise to taxpayers, simply because they were women. Taxation without representation is equally frustrating for both sexes. But the franchise itself was not the only hurdle which had to be overcome and it took the remarkable ability and perseverance of Judge Emily Murphy and her four colleagues to establish once and for all that women were persons. In the intervening time they have entered into the political life of this country at various levels and in various capacities. While it must be admitted that at certain levels of government they have not made as great a contribution as they might have done, I believe that there are very definite reasons for that lack of response. I might mention here that the relatively few women who have succeeded at the elective level in the political life of the country find that the same situation exists in other phases of the economy. For instance, despite the large numbers of women employed in industry today, I am told by the Canadian Labour Congress that only two women in Canada are executives of unions at the top level. The one is Elma Hannah, who is the special representative for Canada in Communications Workers of America, and the other is Huguette Plamondon, President of the Montreal Labour Council.

The same situation occurs in business and finance, where despite the large numbers of women shareholders, the names of relatively few women appear in the lists of directors of Canadian companies. It is my conviction that this situation will change in the next ten years, but I think that I would be dodging facts, if I did not admit that, although legislation has been adopted in most of Canada today which gives equal pay for equal work to men and women, there has as yet not been general acceptance of the principle of equal opportunity. It is my opinion that women themselves must show their willingness to accept responsibility to a greater degree than they have done heretofore. But that is not the whole answer.

I am sometimes amused by the reasons which are given for the non-admittance of women into certain groups, and one of the most common is that men like to talk among themselves and, on occasion, in rather rich language. I can only speak from personal experience. I have been in elective posts of one kind or another for some twelve years now, and before that I worked for many years in organizations where I was frequently the only woman. In that time I do not think my colleagues pulled their punches at all in the matter of language and I solemnly assure you that in that whole period I never learned one word. I am certain that would be the case with any woman who has attended co-educational institutions from kindergarten grade.

Of course, one of the allegations against women which is most frequently heard is that they tend to monopolize the conversation.

No comment!

Despite the work of Emily Murphy and her confreres, there have only been six women appointed to the Senate of Canada, and now there are five sitting in the chamber.

Since 1921 when they were first eligible for election to the House of Commons, there have just been nine women elected, and in this present Parliament there are only two. We do not show up very well in this regard in relation to European countries, but it is my opinion that one of the difficulties is in the size of the territory which is represented. No doubt some of the hesitation on the part of women to offer themselves for election to legislatures and to the House of Commons is the distance which they must necessarily travel in many cases to discharge their duties.

There have never been any women in any of the legislatures east of the Province of Ontario and there has only been one in Ontario. But when we look at the municipal level of government, we find a different picture and I think that this bears out my contention that distance presents one of the main difficulties. It is very hard to arrive at the exact number of women who are serving on municipal councils and school boards, because the information is not available for some of the rural areas, but judging from the number who are recorded, I believe that a reasonable estimate is that there are approximately 1200 women at the present time serving in elective posts at the municipal level across Canada. When you consider in addition to that the number who serve at the non-elective level on hospital boards and local boards of one kind or another, the number must indeed be impressive.

Quite apart from what might be termed political activity, women make a tremendous contribution to Canadian life by their participation in various organizations at the local, national and even the international level. There are the patriotic organizations, the service clubs, the church associations, the Business and Professional Women’s Institutes, the Council of Women and countless others. In all of these women give freely of their time and effort and who can evaluate their contribution to society or their influence?

Without their voluntary efforts, much social welfare work would have to be undertaken by professional workers and paid for by the various levels of government. This, in turn, would impose an additional load on every taxpayer. It is quite possible that this contribution is more apparent to the municipal councillor than it is to those who are members of provincial or the federal government, but certainly there is no municipal councillor who does not realize the great debt which the municipality owes to the citizens, both men and women, who throw themselves wholeheartedly into community activities of all kinds.

Another field which has opened up in the last few years to women is that of jury service. This is one field of responsibility which women have approached with varying feelings of reluctance, but generally speaking with a real desire to accept their responsibilities.

I mentioned a few moments ago that it was my opinion that the next ten years would see great changes in the acceptance of women in responsible posts. By that time I think that half of all women past school age will be working outside their homes, either part-time of full-time.

A United Nations report on ‘Part-Time Work for Women’ discusses the benefits which married and other women gain from part-time work and some of the difficulties they encounter. The report concluded that a parttime job may do a lot to raise morale of women with home responsibilities. Mixing with people and hearing and expressing ideas gives a woman confidence in herself. She may be more conscious of her appearance, manner and speech through her association with the business world. And a part-time job may well give her new perspective.

Part-time work is not necessarily an unmixed blessing, however, as a woman may have to face increased housekeeping costs, and may feel at times that she is neglecting responsibilities in the home. Then she may be faced with some of the difficulties which affect part-time workers of both sexes: she may be hired for a peak period and be required to work disproportionately harder than regular employees; she may be given routine tasks not employing her full capabilities; and she may be among the first dismissed if business conditions become adverse.

There is a trend apparent even now toward the acceptance of the mature women who has shown herself to be the steadiest worker. There will be more programs for the re-training of women in partly forgotten skills, and refresher courses available to those who are engaged in professional pursuits.

Experience has shown that these women can learn new skills, and that they can perform excellent service as stenographers, business machine operators, or in positions of greater responsibility. On this continent there have emerged two significant trends over recent decades: a growing proportion of married women in the labour force, and an increase in the employment of older women.

Once a novelty, women are now a permanent part of the labour force and I quote from the monthly letter of a Canadian bank, released this October:

“The last 50 or 60 years have been years of almost revolutionary change in the status of women, especially in the part they play in the labour force. From representing an insignificant section of the country’s workers, their share in economic life has risen to the point where serious dislocation of the entire pattern of industry, income and production could occur if the direction of change should be reversed. Women in the labour force today are making a vital contribution to Canadian economic development”.

Today, there is one woman for every three men in our labour force, and of these 63 per cent are 25 years of age or over. 23 per cent are 45 years of age or over. Almost 40 per cent of our women workers are married, whereas 25 years ago only 10 per cent were.

All in all, women are contributing their share of the nation’s economy. Women bear a fair share of the country’s tax load. In the latest year for which figures are published by sex (1953), women paid over $147,476,000 in federal income taxes. The class of women who earned the highest incomes per capita and who paid the highest average tax–$207 for the group–was married women with one or two dependents. Single women paid an average income tax of $188, and married women with no dependents $169.

Since the taxation year of 1953 these statistics have not been available, but I notice that the 1956 census shows a total of 464,272 women as heads of families, and the average number of persons per household was 2.6 which means that we had almost one and one-quarter million persons for whose maintenance female workers were responsible. This is 71/z per cent of our population. In addition to the prophecies I have already made, I believe we may expect that the woman’s work load in the home will continue to be reduced, and that women will go out into the world of business in increasing numbers to help their men-folk buy the new and improved washing machines, garbage disposal units and pre-digested dinners. Women may continue to live longer. They may enter more and more into occupations of a technical nature on which increased emphasis is likely to be placed in the age of Sputniks. Incidentally, I notice that the famous rocket expert, Dr. Willy Ley, speaking in Chicago two months ago, said that women probably will pilot the first space ships because they are more adaptable than men to withstand monotonous work under difficult conditions.

Women probably cannot expect an easier life, but they can rather be expected to shoulder a larger share of responsibility as citizens in an increasingly complex world.

THANKS OF THE MEETING were expressed by Mr. James H. Joyce, a Past President of the Club.