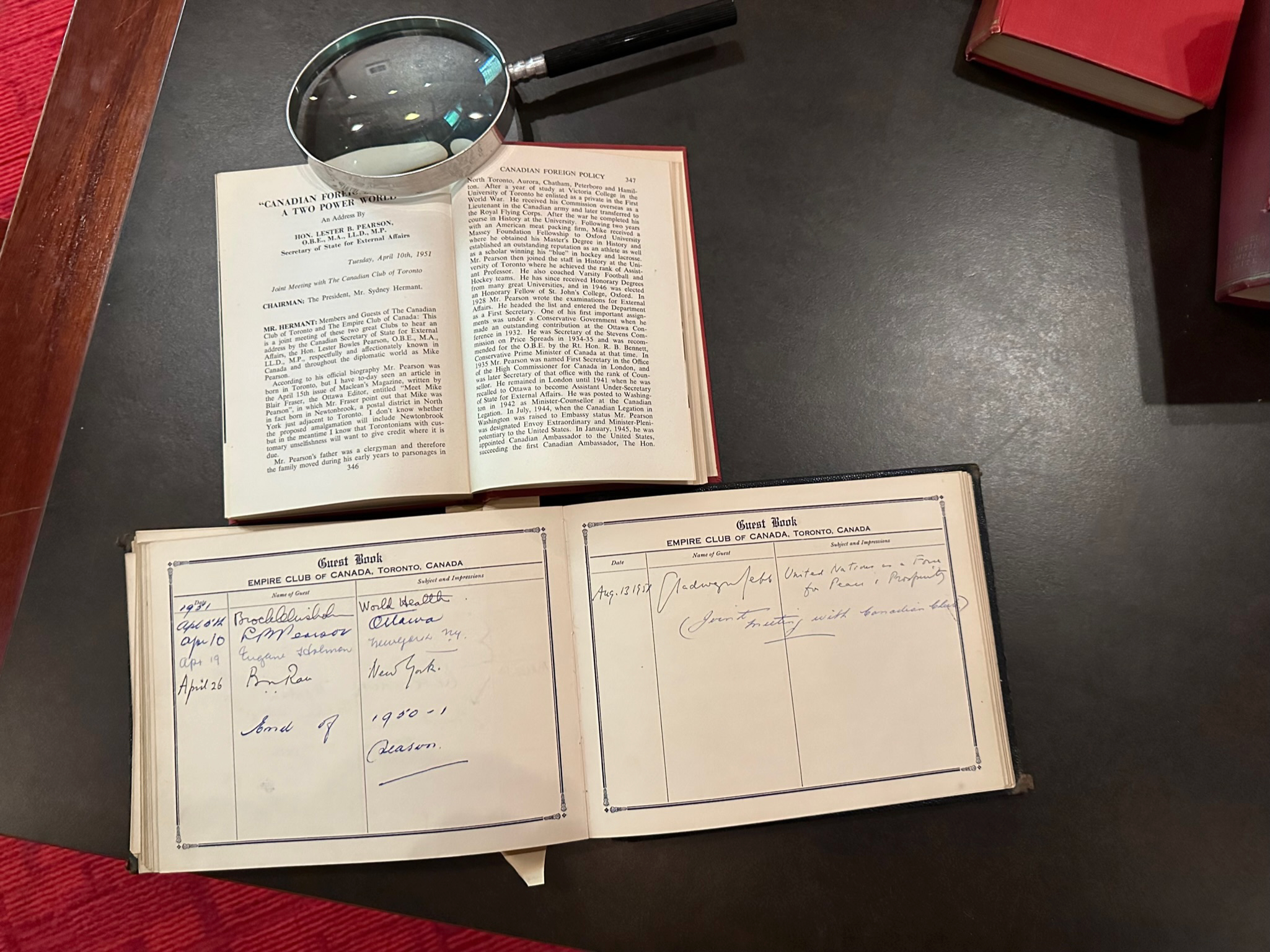

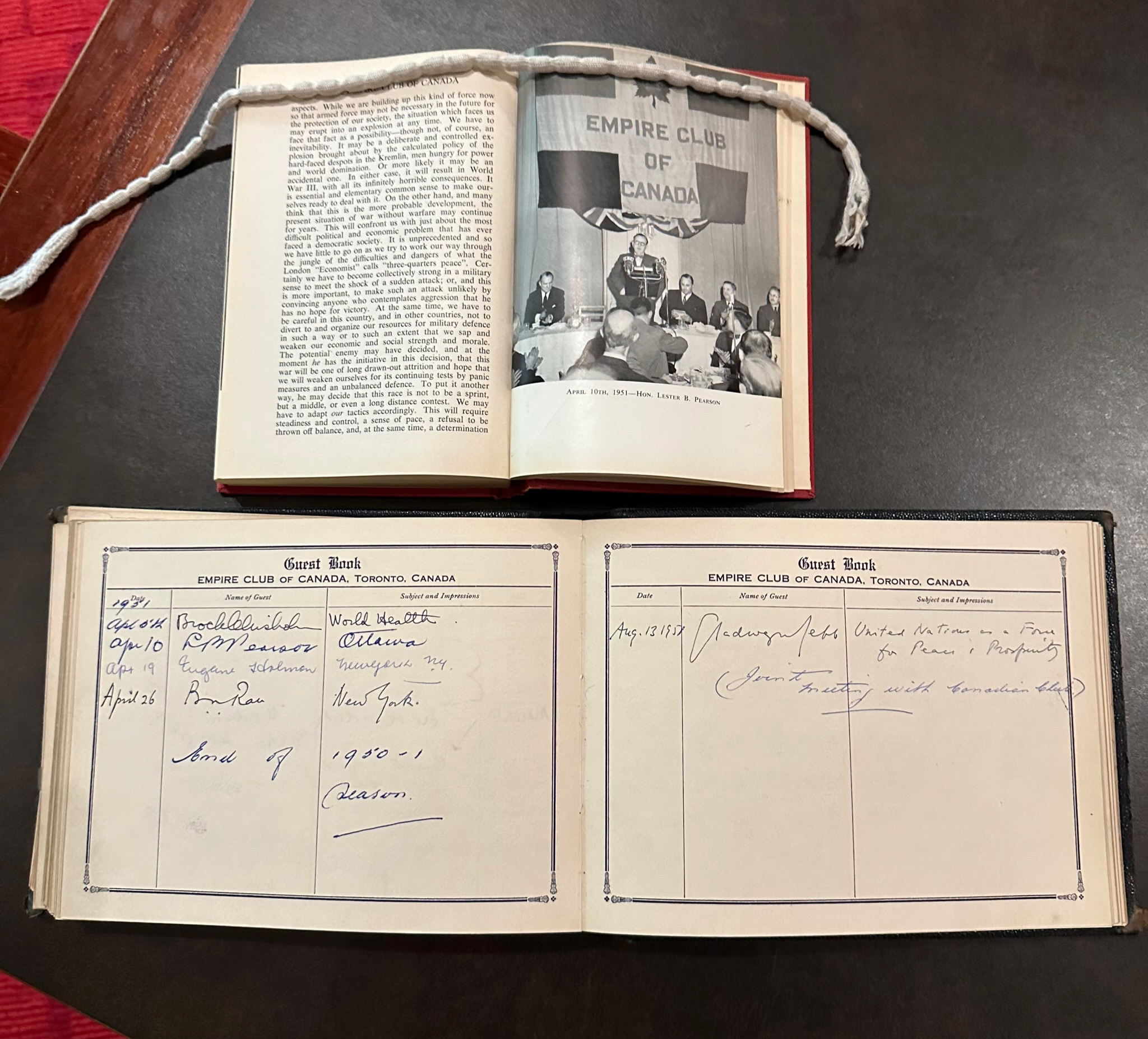

An Address By HON. LESTER B. PEARSON, O.B.E., M.A., LL.D., M.P.

Secretary of State for External Affairs

Tuesday, April 10th, 1951

Joint Meeting with The Canadian Club of Toronto

CHAIRMAN: The President, Mr. Sydney Hermant.

MR. HERMANT: Members and Guests of The Canadian Club of Toronto and The Empire Club of Canada: This is a joint meeting of these two great Clubs to hear an address by the Canadian Secretary of State for External Affairs, the Hon. Lester Bowles Pearson, O.B.E., M.A., LL.D., M.P., respectfully and affectionately known in Canada and throughout the diplomatic world as Mike Pearson.

According to his official biography Mr. Pearson was born in Toronto, but I have today seen an article in the April 15th issue of Maclean’s Magazine, written by Blair Fraser, the Ottawa Editor, entitled “Meet Mike Pearson”, in which Mr. Fraser points out that Mike was in fact born in Newtonbrook, a postal district in North York just adjacent to Toronto. I don’t know whether the proposed amalgamation will include Newtonbrook but in the meantime I know that Torontonians with customary unselfishness will want to give credit where it is due.

Mr. Pearson’s father was a clergyman and therefore the family moved during his early years to parsonages in North Toronto, Aurora, Chatham, Peterboro and Hamilton. After a year of study at Victoria College in the University of Toronto he enlisted as a private in the First World War. He received his Commission overseas as a Lieutenant in the Canadian army and later transferred to the Royal Flying Corps. After the war he completed his course in History at the University. Following two years with an American meat packing firm, Mike received a Massey Foundation Fellowship to Oxford University where he obtained his Master’s Degree in History and established an outstanding reputation as an athlete as well as a scholar winning his “blue” in hockey and lacrosse. Mr. Pearson then joined the staff in History at the University of Toronto where he achieved the rank of Assistant Professor. He also coached Varsity Football and Hockey teams. He has since received Honorary Degrees from many great Universities, and in 1946 was elected an Honorary Fellow of St. John’s College, Oxford. In 1928 Mr. Pearson wrote the examinations for External Affairs. He headed the list and entered the Department as a First Secretary. One of his first important assignments was under a Conservative Government when he made an outstanding contribution at the Ottawa Conference in 1932. He was Secretary of the Stevens Commission on Price Spreads in 1934-35 and was recommended for the O.B.E. by the Rt. Hon. R. B. Bennett, Conservative Prime Minister of Canada at that time. In 1935 Mr. Pearson was named First Secretary in the Office of the High Commissioner for Canada in London, and was later Secretary of that office with the rank of Counsellor. He remained in London until 1941 when he was recalled to Ottawa to become Assistant Under-Secretary of State for External Affairs. He was posted to Washington in 1942 as Minister-Counsellor at the Canadian Legation. In July, 1944, when the Canadian Legation in Washington was raised to Embassy status Mr. Pearson was designated Envoy Extraordinary and Minister-Plenipotentiary to the United States. In January, 1945, he was appointed Canadian Ambassador to the United States, succeeding the first Canadian Ambassador, The Hon. Leighton McCarthy. In Sept. 1946, he was recalled to Ottawa to become Under Secretary of State for External Affairs. On Sept. 10th, 1948, the Rt. Hon. Mackenzie King, Prime Minister of Canada, announced that Mr. Pearson had joined the Cabinet as Secretary of State for External Affairs. As Mr. Fraser points out in his article, this was one of the great decisions of Mr. Pearson’s life. He was giving up the comparative security of the Civil Service for the hazards of party politics although, judging from his majority in his constituency of Algoma-East, in the by-election, and in the general election of June 27th, 1949, and from his present situation, the hazards at least for Mike Pearson don’t seem too great.

Mr. Pearson’s record of service to Canada and the Empire is a most impressive one. His work last December on the three-man Cease Fire Commission of the United Nations, trying to find a peaceful settlement in Korea, established him as an outstanding world figure and emphasized Canada’s growing influence among the Councils of Nations. Mr. Pearson enjoys the dubious distinction of a tribute from the Soviet Foreign Commissar Andrei Vishnisky, who said recently: “I always listen with great attention to the Canadian Delegate, Mr. Pearson, because he often says what other people are afraid to say.”

In this connection I would quote once more from the article in Maclean’s which points out that although he enjoys excellent relations with the press and the public Mr. Pearson gives away no State secrets. Therefore it is most unlikely that we will learn anything at Luncheon today with respect to the Budget coming down in the House this evening unless it is some indication of the necessity for it. It is now my privilege to present the Hon. Lester “Mike” Pearson, Canadian Secretary of State for External Affairs who will address this joint meeting of The Canadian Club of Toronto, and The Empire Club of Canada, on the subject: “Canadian Foreign Policy in a Two-Power World”.

MR. PEARSON: I suppose there never has been a time when the conduct of foreign policy has been more complicated and difficult than at present; or one when the consequences of a mistake could be more disastrous; or indeed when even the wrong kind of speech could make more mischief. One reason is obvious. Our scientific achievements have so far out-stripped our social and moral development that we, in Toronto, can learn in a few minutes of what has happened in Peking, or in Timbuctu, but are not always able to assess the knowledge with objectivity and act on it with mature intelligence. Indeed, too much of our intelligence seems to be devoted to the discovery and perfection of the techniques which bring the news to us; and not enough to the problem of what to do about it.

The formulation of foreign policy has special difficulties for a country like Canada, which has enough responsibility and power in the world to prevent its isolation from the consequences of international decisions, but not enough to ensure that its voice will be effective in making those decisions.

Today, furthermore, foreign policy must be made in a world in arms, and in conflict. In this conflict there are two sides whose composition cuts across national and even community boundaries. The issues have by now been pretty clearly drawn, and at the risk of over-simplification can be described as freedom vs. slavery. Moreover, the two powerful leaders of these opposed sides have emerged–the United States of America and the U.S.S.R.

The struggle has not yet become a shooting war, except in Korea, but is still one of policy. It goes on in the field of economics, finance, and public opinion, and extends far beyond any military or even political operation. It is the more terrifying because, if it breaks into fighting, science will be harnessed to its prosecution as never before–with results almost too horrible to contemplate. Our defence in this conflict must be one of increasing and then maintaining our strength, while always keeping open the channels of negotiation and diplomacy. Strength, however, cannot now be interpreted in military terms alone, but has also its economic, financial and moral aspects. While we are building up this kind of force now so that armed force may not be necessary in the future for the protection of our society, the situation which faces us may erupt into an explosion at any time. We have to face that fact as a possibility–though not, of course, an inevitability. It may be a deliberate and controlled explosion brought about by the calculated policy of the hard-faced despots in the Kremlin, men hungry for power and world domination. Or more likely it may be an accidental one. In either case, it will result in World War III, with all its infinitely horrible consequences. It is essential and elementary common sense to make ourselves ready to deal with it. On the other hand, and many think that this is the more probable development, the present situation of war without warfare may continue for years. This will confront us with just about the most difficult political and economic problem that has ever faced a democratic society. It is unprecedented and so we have little to go on as we try to work our way through the jungle of the difficulties and dangers of what the London “Economist” calls “three-quarters peace”. Certainly we have to become collectively strong in a military sense to meet the shock of a sudden attack; or, and this is more important, to make such an attack unlikely by convincing anyone who contemplates aggression that he has no hope for victory. At the same time, we have to be careful in this country, and in other countries, not to divert to and organize our resources for military defence in such a way or to such an extent that we sap and weaken our economic and social strength and morale. The potential enemy may have decided, and at the moment he has the initiative in this decision, that this war will be one of long drawn-out attrition and hope that we will weaken ourselves for its continuing tests by panic measures and an unbalanced defence. To put it another way, he may decide that this race is not to be a sprint, but a middle, or even a long distance contest. We may have to adapt our tactics accordingly. This will require steadiness and control, a sense of pace, a refusal to be thrown off balance, and, at the same time, a determination to take the necessary steps to cut down the lead which our opponent now has. The present conflict is, in fact, a dual one, and requires dual policies–short term and long term policies–military and civil–which should be complementary and not contradictory. We are faced now with a situation similar in some respects to that which confronted our fore-fathers in early colonial days when they ploughed the land with a rifle slung on the shoulder. If they stuck to the plough and left the rifle at home, they would have been easy victims for any savages lurking in the woods. If they had concentrated on the rifle and forgot about ploughing, the colony would have scattered or died. The same combination is required today, though it is far more difficult to bring about. We must keep on ploughing, harder than ever, while we arm. We can certainly never achieve that double objective by government as usual, by business as usual or by life as usual.

These are all generalities, and you have heard them many times before. More important are the practical problems they present to us, one or two of which I would like to mention.

In domestic policy, one of our main problems is to decide what proportion of our resources should be devoted to our own defence, whether that defence takes the form of national action at home or collective action with our friends abroad. There should be no distinction–this time–between them. We should accept without any reservation, the view that the Canadian who fires his rifle in Korea or on the Elbe is defending his home as surely as if he were firing it on his own soil. There is not likely, certainly, to be unanimous agreement on this question of how much should go now for defence. Some will say that we are actually and completely at war now; that we should base all our policy on that fact; that our military defence efforts should be the same as if the enemy were actually attacking our country; that our economic policy should be based on the same considerations, with complete control of prices and wages and, above all, of manpower for industry or for the armed services. There are others, and the Government shares this view, who feel that any such all-out interference with the mechanism of our economic and political society, at the present time, would weaken, rather than strengthen us–might, indeed, even play into the enemy’s hands by making it harder for us to maintain our unity, our morale and our strength over the long pull ahead.

The same division of opinion naturally exists in regard to our proper part in collective international action. There are those who say that we have not so far pulled our weight here, except possibly our oratorical weight. There are others who complain that we are doing too much, especially as the big decisions which will decide the course of events will not be made primarily by us but by others. It is, of course, comforting for one who has some responsibility in these matters to conclude that if you are attacked from both sides, you have a fairly good chance of being right. But I certainly would not wish to carry that analogy too far. It may mean merely that you are doubly wrong! We all agree, however, that we must play our proper part, no less and no more, in the collective security action of the free world, without which we cannot hope to get through the dangerous days ahead. But how do we decide what that proper part is, having regard to our own political, economic and geographical situation? It is certainly not one which can be determined by fixing a mathematical proportion of what some other country is doing. As long as we live in a world of sovereign states, Canada’s part has to be determined by ourselves, but this should be done only after consultation with and, if possible, in agreement with our friends and allies. We must be the judge of our international obligations and we must decide how they can best be carried out for Canada, but we have no right to make these decisions in isolation from our friends. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization is, I think, a good example of what I mean. The Council of this Organization, or its Deputies, is meeting almost continuously, mainly for the purpose of collective defence planning. The recommendations–because they are only recommendations–made through this collective process are then sent to the separate governments for decision, but no government is likely to reject them without very good reason indeed. The military tasks for the separate members under the North Atlantic Treaty Organization have been worked out collectively in detail. Those allotted to Canada, which were considered by all the members of the group to be fair and proper, have been accepted by the Canadian Government and will be carried out once Parliament approves them.

There is another aspect to this problem. What should our role be in the United Nations? Indeed, what should the role of the world organization itself be in the present conflict? I have tried to make my own views known in this matter in recent statements, and I do not wish to go over the ground again here. But I would say this; that we must be sure, so far as we can ever be sure, that the United Nations remains the instrument of the collective policy of all its members for the preservation of peace and the prevention or defeat of aggression, and does not become too much the instrument of any one country. I am not suggesting that this has happened or is going to happen, but it is something that we should guard against. If, however, the United Nations is to be such a genuine international organization in this sense, all of its members, except the Soviet Communist bloc who have no interest in it except as an agency for advancing their own evil purpose, must play a part in deed as well as in word. We must be careful not to be stampeded into rash decisions which cannot be carried out but we must all contribute to the implementation of decisions freely and responsibly made. I do not think that we in Canada have any reason to apologize for the part that we have played in this regard. Our record in the United Nations is a worthy one. However, I do not think that we should be asked, in the United Nations or elsewhere, to support automatically policies which are proposed by others if we have serious doubts about their wisdom. We must reserve the right, for instance, to criticize even the policy of our great friend, the United States, if we feel it necessary to do so. There are two reservations to this. First, we must recognize and pay tribute to the leadership being given and the efforts being made by the United States in the conflict against Communist imperialism, and realize that if this leadership were not given we would have little chance of success in the common struggle. Secondly, we must never forget that our enemy gleefully welcomes every division in the free democratic ranks and that, therefore, there will be times when we should abandon our position if it is more important to maintain unity in the face of the common foe. This reconciliation of our right to differ and the necessity for unity, is going to be a tough problem for anyone charged with responsibility for foreign policy decisions in this, or indeed in any free country.

This brings me squarely up against a matter which is very much in my mind, as I know it is in yours, the question of Canadian-American relations in this two-power world of conflict. It is, I think, one of the most difficult and delicate problems of foreign policy that has yet faced the Canadian people, their Parliament and their Government, and it will require those qualities of good sense, restraint, and self-reliance which the Canadian people have shown in the past. It was not so long ago that Canada’s foreign relations were of importance only within the Commonwealth, more particularly in our relations with the United Kingdom. These former Canadian-Commonwealth problems seem to me to have been now pretty well solved. At least the right principles have been established and accepted which makes their solution fairly easy. We have in the Commonwealth reached independence without sacrificing co-operation. We stand on our own feet, but we try to walk together. There is none of the touchiness on our part, which once must have complicated relations with Downing Street, and there is now certainly none of the desire to dominate which we used to detect in Whitehall. We have got beyond this in Canada-U.K. relations, and we deal with each other now, on a basis of confidence and friendship, as junior and senior partners in a joint and going concern. In our relations with the United Kingdom we have come of age and have abandoned the sensitiveness of the debutante.

This has been made easier because any worry we once may have had, and we had it, that British imperialism or continentalism might pull us into international wars not of our own making or choosing, has passed. We now accept the Commonwealth of Nations as a valuable and proven instrument for international co-operation; as a great agency for social and economic progress, and possibly, at the present time, most important of all, as a vital and almost the only bridge between the free West and the free East. I think also that in the post-war years we have come to appreciate, as possibly never before, the wisdom, tolerance, and far-sighted steadiness of vision of the British people. As their material power has decreased, at least temporarily, because of the unparallelled sacrifices they have made in two world wars, I think that our need for these other British qualities has increased in the solution of international difficulties. This, in my mind, has never been shown more clearly than in the events of the last six’ months at the United Nations.

With the United States our relations grow steadily closer as we recognize that our destinies, economic and political, are inseparable in the Western hemisphere, and that Canada’s hope for peace depends largely on the acceptance by the United States of responsibility for world leadership and on how that responsibility is discharged. With this closeness of contact and with, I hope, our growing maturity goes a mutual understanding and a fundamental friendliness. This makes it possible for us to talk with a frankness and confidence to the United States, which is not misunderstood there except possibly by a minority who think that we shouldn’t talk at all, or who complain that if we do, our accents are too English! But we need not try to deceive ourselves that these close relations with our great neighbour will always be smooth and easy. There will be difficulties and frictions. These, however, will be easier to settle if the United States realizes that while we are most anxious to work with her and support her in the leadership she is giving to the free world, we are not willing to be merely an echo of somebody else’s voice. It would be easier also if it were recognized by the United States at this time that we in Canada have had our own experience of tragedy and suffering and loss in war. In our turn, we should be careful not to transfer the suspicions and sensitiveness and hesitations of yesteryear from London to Washington. Nor should we get unduly hot and bothered over all the pronouncements of journalists or generals or politicians which we do not like, though there may be, indeed are some on which we have a right to express our views. More important, we must convince the United States by action rather than merely by word that we are, in fact, pulling our weight in this international team. On their side, they should not attempt to tell us that until we do one-twelfth or one-sixteenth, or some other fraction as much as they are doing in any particular enterprise, we are defaulting. It would also help if the United States took more notice of what we do, and, indeed occasionally of what we say. It is disconcerting, for instance, that about the only time the American people seem to be aware of our existence, in contrast say to the existence of a Latin American republic, is when we do something that they do not like, or do not do something which they would like. I can explain what I mean by illustration. The United States would certainly have resented it, and rightly so, if we in Canada had called her a reluctant contributor to reconstruction in 1946 because her loan to the United Kingdom was only three times as large as ours, while her national income was seventeen or eighteen times as large. In our turn, most of us resent being called, by certain people in the United States, a reluctant friend because Canada, a smaller power with special problems of her own, ten years at war out of the last thirty, on the threshold of a great and essential pioneer development, and with half a continent to administer, was not able to match, even proportionately, the steps taken by the United States last June and subsequently, which were required by United Nations decisions about Korea.

The leadership then given by the United States rightly won our admiration, and the steps that she has taken to implement them since, deserve our deep gratitude. The rest of the world naturally, however, took some time to adjust itself to a somewhat unexpected state of affairs. Canada, in my view at least, in not making the adjustment more quickly, should surely not be criticized more than, say Argentina or Egypt, or Sweden.

There may be other ripples on the surface of our friendship in the days ahead, but we should do everything we can in Canada, and this applies especially to the Government, and in the Government particularly to the Department of External Affairs, to prevent these ripples becoming angry waves which may weaken the foundation of our friendship. I do not think that this will happen. It will certainly be less likely to happen, however, if we face the problems frankly and openly of our mutual relationship. That relationship, as I see it, means marching with the United States in the pursuit of the objectives which we share. It does not mean being pulled along, or loitering behind.

Nevertheless, the days of relatively easy and automatic political relations with our neighbour are, I think, over. They are over because, on our side, we are more important in the continental and international scheme of things, and we loom more largely now as an important element in United States and, in free world plans for defence and development. They are over also because the United States is now the dominating world power on the side of freedom. Our preoccupation is no longer whether the United States will discharge her international responsibilities, but how she will do it and how the rest of us will be involved. You may recall that it was not many years ago that Colonel Lindbergh suggested that Canada should be detached from membership in the British Commonwealth of Nations because that international affiliation of ours might get the United States into trouble by involving the larger half of North America in European wars. That seems a long time ago. There are certain people in Canada (I am not one of them) who think that the shoe, if not already on the other foot, is now being transferred to the other foot.

From what I have said, and I have only touched on the subject, you will appreciate that the days have gone when the problems of Canadian foreign policy can be left to a part-time Minister; to a small group of officials; to a couple of hours’ desultory and empty debate each session, in Parliament, and to the casual attention of public opinion when it can turn from more important matters such as the Stanley Cup or the stock market.

Foreign affairs are now the business of every Canadian family and the responsibility of every Canadian citizen. That includes you and also the Minister for External Affairs. I hope that we will together be able to bring to these problems, so complicated and so exacting, the good judgment, the calm objectivity and the sense of responsibility which they require.

VOTE OF THANKS, moved by Mr. R. F. Chisholm, President of The Canadian Club of Toronto.