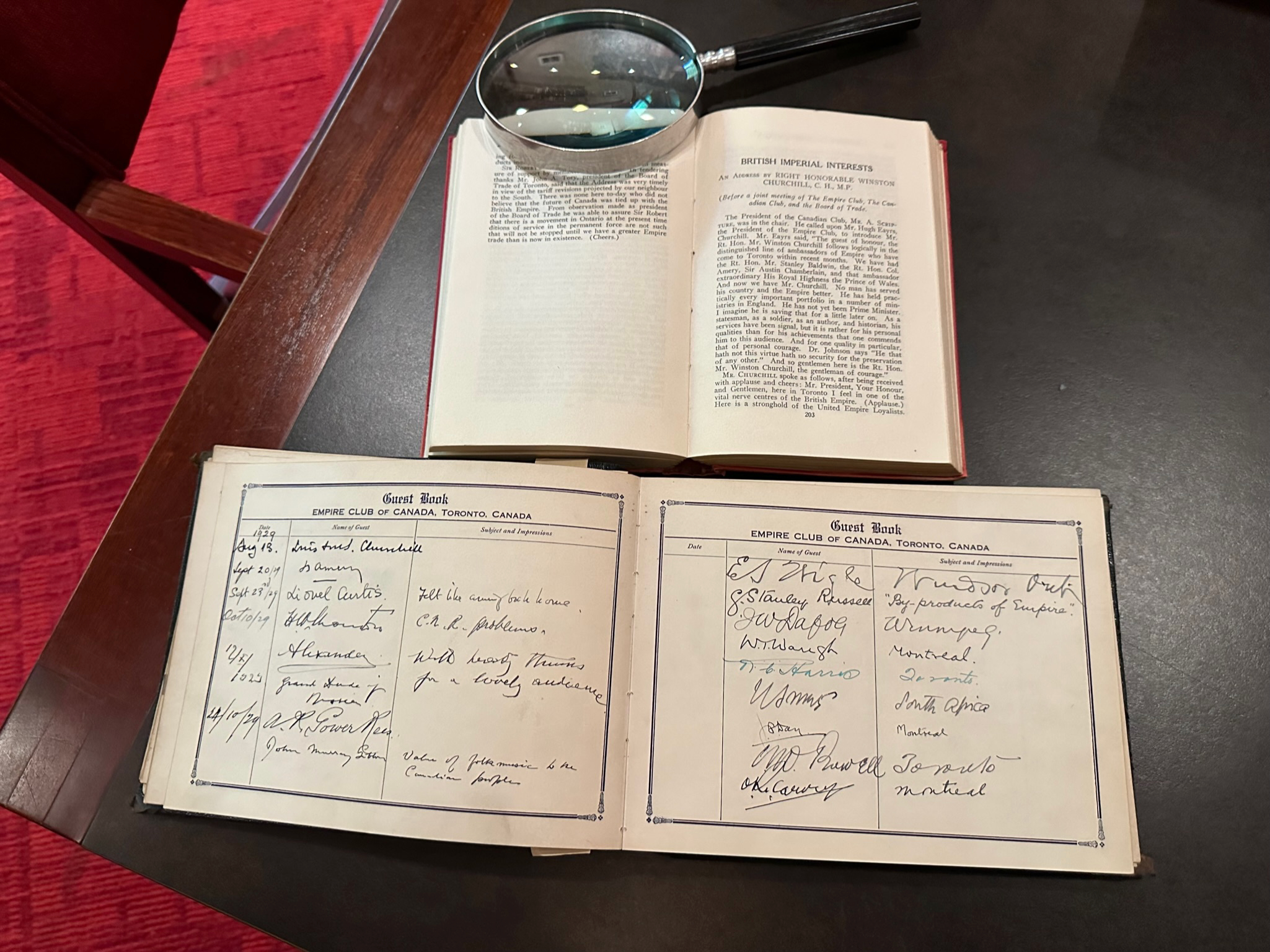

BRITISH IMPERIAL INTERESTS AN ADDRESS BY RIGHT HONOURABLE WINSTON CHURCHILL, C. H., M.P. (Before a joint meeting of The Empire Club, The Canadian Club, and the Board of Trade.)

The President of the Canadian Club, MR. A. SCRIPTURE, was in the chair. He called upon MT. Hugh Eayrs, the President of the Empire Club, to introduce Mr. Churchill. Mr. Eayrs said, “The guest of honour, the Rt. Hon. Mr. Winston Churchill follows logically in the distinguished line of ambassadors of Empire who have come to Toronto within recent months. We have had the Rt. Hon. Mr. Stanley Baldwin, the Rt. Hon. Col. Amery, Sir Austin Chamberlain, and that ambassador extraordinary His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales. And now we have Mr. Churchill. No man has served his country and the Empire better. He has held practically every important portfolio in a number of min istries in England.He has not yet been Prime Minister.

I imagine he is saving that for a little later on. As a statesman, as a soldier, as an author, and historian, his services have been signal, but it is rather for his personal qualities than for his achievements that one commends him to this audience. And for one quality in particular, that of personal courage. Dr. Johnson says “He that hath not this virtue hath no security for the preservation of any other.”And so gentlemen here is the Rt. Hon. Mr. Winston Churchill, the gentleman of courage.” MR. CHURCHILL spoke as follows, after being received with applause and cheers: Mr. President, Your Honour, and Gentlemen, here in Toronto I feel in one of the vital nerve centres of the British Empire.(Applause.)

Here is a stronghold of the United Empire Loyalists Here too are many of those who have cherished affection and affinities with Northern Ireland, with Ulster. I have had many ups and downs with Ulster. I remember in the bitter party struggles which in Great Britain preceded the Great War, that I had a quarrel with Ulster, but I have been forgiven. (Laughter.) I have renewed a friendship with Ulster that I might have inherited from my father, and I know that when Ulstermen make friends, they make them for a long time.

I am going to speak to you to-day upon some subjects of general interest to patriotic British citizens in every part of His Majesty’s domain. Let me begin by saying what I said at Montreal, do not form too gloomy an opinion of the strength and prosperity of the Mother Country. (Hear, hear, and applause.) You know what English people are, how they always criticize themselves and dwell on the dark side of their affairs, and so from time to time are able to make improvements, and correct errors and abuses in their way of carrying on. But it is absolutely necessary that on this side of the Atlantic Ocean there should be no misconception of the giant strength of Britain. (Hear, hear and applause.) Never before this present year have there been so many people in the Islands, never before have they been so well fed, never before have there been so many people employed in the Islands, and never before, except in the temporary convulsions of the war, have their real wages constituted a greater reward for their exertion. (Applause.) We have paid our debts-(Hear, hear and applause)-we are paying our way, we are providing for the carrying of our national debt and for its extinction in fifty years, no less than 350 million sterling per annum.(Applause.) Taxation is faithfully collected and faithfully paid. We are still the greatest creditor nation in the world. (Applause.) We have repaired since the war the ravages upon our foreign investments, which the war created, and to-day our holdings overseas throughout the Empire and in foreign lands stand substantially higher than at any period in our history. (Applause.) We have enormous difficulties. We have immense and intricate problems. But we are facing our difficulties, we are driving through our problems and if I come here to talk to this great buoyant expanding city of Canada, I wish to present myself before you as a citizen of a country which old as she is, developed as she is, explored as she has been for so many generations, is nevertheless growing steadily in wealth, in power, in knowledge, and in strength.(Applause.)

I said also at Montreal that the first interest of the British Empire was peace. (Hear, hear and applause.) We have all that we require. We have coveted no man’s territory, we are jealous or envious of no man’s glory. We have our own repute, our own interests, our vast possessions in every corner of the globe, under every sky and clime, we have resources sufficient to occupy all the energy and skill of all our peoples for generations and centuries to come. We envy no one. We have a great inheritance, and we are content to develop that. All we require for its development from others, is peace, and that, I believe, is in no danger at the present time. (Applause.) Peace, I believe, is securely established, and I think Mr. Hoover was quite right in saying the prospects of peace were better than they had been for fifty years. Peace, I mean, between the great civilized nations of the world. I do not mean what disturbances may occur in barbarous parts of the world where the Russian Bolsheviks come in contact with other nations; but as far as the great civilized powers are concerned, I believe the foundations of peace are stronger now than they have ever been in our lifetime. (Applause.)

But, gentlemen, we must be careful of one thing. Subversive propaganda takes many different forms and disguises, and we must be careful that the love of peace, the sincere resolve to maintain peace, which is so universal through all the nations which felt the wounds of the Great War, we must be careful that that love of peace is not used as a cloak to press forward proposals which would weaken or injure the enduring strength of the British Empire. (Hear, hear and applause.) We must be careful that subversive movements do not effectually masquerade in the cause of pacificism and philanthropy. I dare say you have seen for yourselves how again and again certain classes of people go about to coax, cajole, cozen, and if they could, coerce the British Empire into giving up its rights, its interests and instruments of its vital security. (Applause.) Our first security is the navy. (Applause.) Our first security under Providence, and our righteous behaviour, is the Royal Navy. We have long enjoyed the naval supremacy of the world. We did not abuse that supremacy. We laid our ports open-those that were under the control of the central government-to the trade of all nations as well as of our own.We swept the seas of the slave trader, we used our influence for peace during the whole of the 19th century, and when the 20th century dawned it was the British Navy that proved the sure shield of freedom and civilization, and it was the British Navy that enabled the great republic of the United States to bring its influence to bear upon the closing phases of the war.(Applause.) After the war was over, we agreed in the Washington Conference of 1921 that the two great branches of the English-speaking world, the British Empire and the United States, should have equal battle fleets, and in that sense be equal powers upon the seas, but we carefully and specifically reserved the programmes of cruisers and small craft, for this reason that our conditions are so utterly different from those of the United States that it was evident that in this defensive sphere of trade protection was required a different measure and different method of defence than they did. There never were two nations, two countries, more differently situated and circumstanced from the point of view of naval danger than the United States and Great Britain. The United States is almost a continent. It possesses within its bounds everything that is required to minister to its prosperity and life. We are a small, densely populated island with the need of importing threequarters of the food we eat across salt water, and most of our raw material; and we are also the centre of an Empire which circles the globe, the only material connection between the component parts of which is the uninterrupted passage of ships across the seas. We are close to Europe, involved in all its dangers, though we keep as clear of them as we can, whereas the United States may rejoice in having thousands of miles of ocean between her and any enemy or danger, however speculative or impossible that danger may appear. I say there is an immense disparity of conditions between the two parties in this matter; and to apply a mere cheap logic, numerical parity to conditions which are in themselves so fundamentally disparate is not to arrive at what I am willing to arrive at, what I think we are entitled and justified in seeking, namely that the British Empire and the United States should be equal powers upon the sea; we should not arrive at that goal, the true goal, but arrive at the position where under the pretense of a power equality, Great Britain would be in fact relegated to permanent inferiority on the seas. (Applause.) That is a result, I earnestly hope, we may avoid. And more’over let me say, why should we feel anxious about the American naval program? We know perfectly well that whatever ships they may think it right to build will never be used against us. We are sure of that(Applause.) We know that our course and conduct will be such that no quarrels will arise; we know that the ties of friendship and commerce are linking us year by year more closely to each other, and have we not just signed in the Kellogg Pact a solemn instrument regulating the future peace of the world, and finally and definitely outlawing war as a feature in the policy of civilized states. Let us therefore labour to get a satisfactory agreement with the United States, and if that agreement cannot be reached, let us make a friendly agreement to go our ways in peace and in friendship, acting in a sober, reasonable, and neighbourly fashion, and building no more vessels than we each think we require for our own purposes and at our own discretion.(Applause.)

There is another instance where subversive activities inside the British Empire tend to work injury to our imperial interests. I take the case of Egypt, and I am sure you would wish me to say a few words upon that burning topic to-day. (Hear, hear, and applause.) Let us look back and see why it was we went to Egypt. We went to Egypt because Egypt was in a state of chaos and bankruptcy and languishing under a harsh Oriental despotism. We went to Egypt because Egypt has always been to a very large extent a matter of European and international concern. The men of every race in Europe have connections and business interests in Egypt, and the condition of chaos in that country was intolerable. But if any country went there, it was most necessary that the predominant power should be Great Britain, because of the Suez Canal which is our vital connection with India and with Australia and New Zealand. We went to Egypt, and nearly fifty years have passed since we went. Every phase of Egyptian life has been improved. The cruel tyranny has been lifted from the Egyptian peasant; their water supplies have been enormously developed; the wealth of the country has gone ahead always, the wealth of this country, the oldest in the world, has gone forward almost as if it were in the new world, in Canada. A marvelous work, to which we are entitled to look back with pride and satisfaction. Our responsibilities in Egypt are direct. We have responsibilities for the protection of foreigners, of foreign powers; we have a responsibility for the protection of minorities. All these responsibilities have been accepted by us before all the world, and I ask this: No one can say I am an enemy of self-government, I have been responsible myself for actually conducting through the House of Commons the two most daring experiments in self-government that any country has made-the Transvaal Constitution in 1906, and the Irish Free State Constitution in 1921. (Applause.) I ask myself gravely, are the Egyptians more capable of giving good government to Egypt, of creating those conditions of stability and order in Egypt which Europe requires, than they were in 1881 ? Certainly in so far as we have handed over in late years services to the Egyptians, for them to administer, and have withdrawn the guidance of parliamentary control, we have seen a marked deterioration in those services, whether they be services of irrigation or of other forms of public work throughout Egypt. And I am bound to say that it is only four years ago that the conditions in Cairo were those of incipient disorder of a very grave kind; murder and conspiracy were rife, and foreign communities expressed the deepest anxiety as to their personal and individual security. Well, what is it that is now proposed? It is proposed that the British garrisons should be withdrawn from Cairo and Alexandria, they should evacuate those centres of control where they served as the foundation for a beneficent and ameliorating influence upon Egyptian affairs, that they should be withdrawn and that we should dig ourselves in along the Suez Canal, leaving Egypt to go if she pleases to wrack and ruin; and that at the same time we should forbid any one power to come effectively to her aid. I know well that this policy has come into force by gradual steps during ‘the last eight or nine years, and I must admit that the late government went a long way in this direction. But when we survey the position as a whole, when we look at the scene in its full compass and extent, I am bound to say I feel the gravest misgivings about the proposals which have recently been made. It seems to me a weak policy, a selfish policy, and in a sense a dog-in-the-manger policy; it is certainly a melancholy abdication of duty which we owed not only to the citizens of the various states of Europe, but which we also owe to the Egyptian peasantry itself, and I cannot believe that such a policy, if it should be adopted, will be found to have a permanent continuation. Parliament has yet to decide, and it has been definitely promised by the present British administration that the Dominions shall be consulted.Australia and New Zealand have a vital interest, because the Suez Canal is the actual channel of communication which joins them to the Motherland, and Europe, and they have a right to be heard because it was Australian and New Zealand troops which defended Egypt and held the line of the Canal against the Turkish invaders. (Applause.) Gentlemen, the British Government has promised that the Dominions shall be consulted and that Parliament shall know what their views are before it has to take the decision which will be asked of it in the autumn. And I would venture to say this: it seems a long way from Toronto to Cairo, but Canada has an interest as a partner in the Empire in the decision of these great matters. Anything that happens injuriously to the interests of Australia and New Zealand must affect Canadian interests and Canadian sentiment. (Hear, hear.) Anything that affects the welfare of the whole affects the welfare of every part. Canada should have her opinion upon this subject of Egypt too. (Applause.)

Now I come to another stage in connections between the Mother Country and Australia, I come to Singapore. What is Singapore? It is a resting place, a fuelling place, for the British Fleet, to enable the British Fleet to go, if need be, to the rescue of Australia and New Zealand. That is what Singapore is for and that is the only thing it is for. People have suggested that it is a menace to Japan, but we always have the most friendly relations with Japan. No conceivable quarrel could arise between us and Japan.But our Empire must be buckled together by some effective lines of communication, and unless the British Fleet has this half-way house where it can rest and refresh and base itself, the contact is lost between Australia and New Zealand, and the Mptherland and the rest of the Empire. Australia and New Zealand and the Straits Settlements and Hong Kong have made contributions to the building of this harbour, which exceed those which the Mother Country has made up to the present time. And I say to stop that work, to arrest this task in which the Empire has been engaged, just because there is a change of Government in the Mother Country, would be a disastrous set-back. We all remember what the Anzacs did in the Great War. (Applause.) And you, many of whom no doubt served in the Canadian Corps, you know what a comfort it was to find those valiant troops not far away, and ready to come into action in aid of the Canadian Corps. They came to our aid, and I say we must make sure that if they were in trouble, if anything arose which endangered those communities far away in the Pacific, under the Southern Cross, we must be sure that we could come to their aid with all the strength that we could muster. (Hear, hear and applause.)

I spoke at Ottawa yesterday upon Empire trade. What can we do to make more of it, to keep more business, to make business flow more easily, within the circle of the British Empire? What can we do to make the Dominions of the Crown more consciously a single economic unit? and even perhaps, to some extent, and as far as possible, a single fiscal unit? That is an urgent question. You know from your own experience how important it is that we should find means of – handling large blocks of each other’s business, much — larger blocks than we have heretofore. (Hear, hear.) Now there are some things we cannot do. I will give you my opinion as a politician of thirty years’ experience in the United Kingdom. I am sure that it would fatally injure the prospects of any political party in Great Britain if they were to declare their intention of taxing food. On the other hand I think it is more than we could ask of Australia and of Canada that they should throw down their tariff protection on their manufactures and expose themselves freely to the competition of our extremely robust and long-established British industries.

But that by no means exhausts the possibilities.Modern business sees the means of new solutions for old problems, and I say a way must be found.Where there is a will there is a way.Do not let us be deterred by difficulties. I have made a practical proposal; it is a very modest proposal. I proposed yesterday, and I repeat it here, that the leading business men, the great captains of industry, four or five men, who would be judged to be ‘. the outstanding figures in developing the economic life of Canada, or of Australia, or of South Africa, should meet together with the leaders of British industry, and that they should quietly and soberly examine the whole problem upon its merits, without any thought of party politics or what party is going to get the credit of it, or who is going to score over the other man in any election in Great Britain, but that they should look at it as a business proposition, just as men would do if they were brought together on a Board of Directors to see what could best be done for what is after all the greatest merger that has ever been thought of in human experience.(Hear, hear and applause.)Then when they are able to say in what ways they consider intra-imperial trade could be fostered and developed, when we have their plan before us, then will be the time for the parliaments and parties to consider what they will do, and then will be the time for the Imperial Conference to ratify as much as is possible of a practical scheme. Now it seems to me that these are the sensible steps that can immediately be taken, and I say, do not let us be appalled by difficulties. Let us push forward and tackle the difficulties by practical methods. After all, look what difficulties we have overcome in the past. When I was a schoolboy at Harrow

I heard a lecture from a countryman of yours, I believe he came from this city, Sir George Parkin. He lectured e’, on the subject of Empire Unity and Federation, and I.J sat, a little boy in an Eton jacket, and listened to his words.I remember that he said that at the Battle of _d Trafalgar, Nelson had set the signal flying “England expects that every man this day will do his duty.” Oh,’, he said, if you take the steps that are necessary to bind. together and hold together the great Empire to the’ Crown, and if at some future time danger and peril strikes at the heart and life of that Empire, then the signal. will run, not along a line of battle ships but a line of nations.

That is what Sir George Parkin said. I did not see him for 25 years or more and when I saw him it was at a banquet-not so large as this, indeed, but one of those great celebrations held to rejoice that victory had been won in the greatest of all wars, and that peace was now restored. And I went across the room to him and I said do you remember the words you spoke thirty years ago in your lecture, and he remembered that. All his dreams had come true, the dreams and hopes that no one would have dared even to breathe in many quarters before the war have been accomplished as actual facts. Miracles, as they would have been regarded by Victorian statesmen, have happened as the inevitable results of circumstancs. The Empire has passed through the fire of war; the signal for help, the signal to arms was prepared along a line of nations which surround the world; and if ever again a peril loomed upon us we are confident it would be repeated again. (Hear, hear and applause.)

I have spoken to you about the importance of fostering intra-imperial trade, but there are other and far stronger bonds which unite the British Empire.Mr. Disraeli said, and it was one, I think, of his most notable sayings, “There are only two ways of governing peoples-force, and tradition. “A pregnant saying. In the British Empire we rely upon tradition. After the Imperial Con-‘ ference of 1927, there is nothing to hold the British Empire together except its own interests and the far ,stronger connections of good will and good sense, sentiI ment and tradition operating in perfect freedom.Those are ties incomprehensible to some of our European ‘neighbours which have proved in the past strong enough to draw half a million men three thousand miles across the ocean from Canada to the bloody battle fields of Europe.Those are the ties that have drawn one-tenth of the population of the whole of New Zealand half way around the world to fight in the Empire’s cause. Invisible but indissoluble ties. We may trust to them, we may trust to them as the years go by to gain and grow in strength and force. We may trust to them to enable the wonderful association of states and of peoples, the like of which the world has never seen, our commonwealth of free nations; they will enable us to tread the path of destiny hand in hand and side by side, sure that whatever the future may have in store, union and freedom will lead the Empire to safety, and will keep us at least the equal of any organization known to man.(Long applause.)

Mr. John Tory, President of the Toronto Board of Trade, expressed to the speaker the thanks of the gathering, after which the meeting gave three cheers for Mr. Churchill.