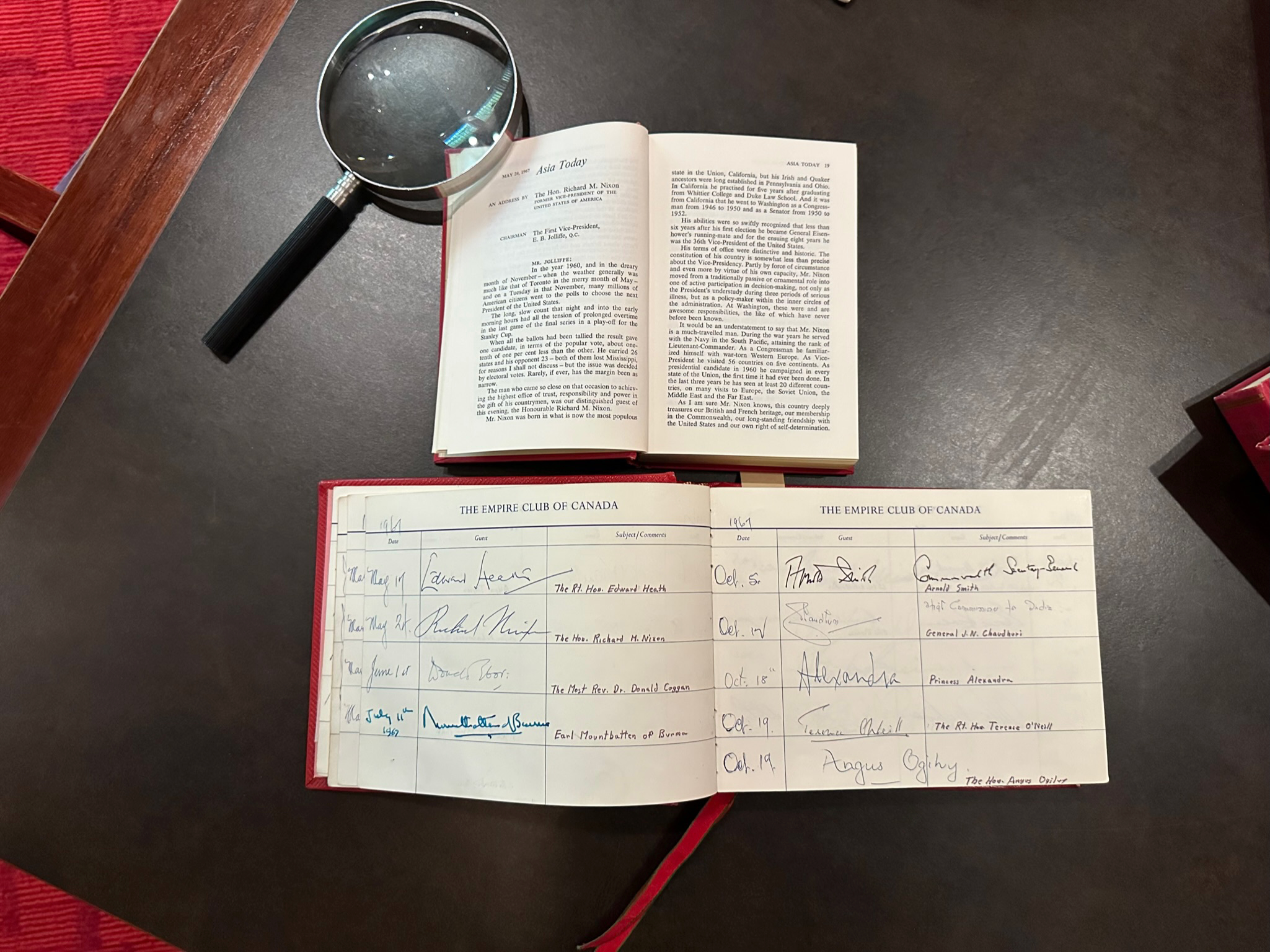

MAY 24, 1967 Asia Today

AN ADDRESS BY The Hon. Richard M. Nixon FORMER VICE-PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

CHAIRMAN, The First Vice-President, E. B. Jolliffe, Q.C.

MR. JOLLIFFE:

In the year 1960, and in the dreary month of November-when the weather generally was much like that of Toronto in the merry month of May–and on a Tuesday in that November, many millions of American citizens went to the polls to choose the next President of the United States.

The long, slow count that night and into the early morning hours had all the tension of prolonged overtime in the last game of the final series in a play-off for the Stanley Cup.

When all the ballots had been tallied the result gave one candidate, in terms of the popular vote, about onetenth of one per cent less than the other. He carried 26 states and his opponent 23–both of them lost Mississippi, for reasons I shall not discuss–but the issue was decided by electoral votes. Rarely, if ever, has the margin been as narrow.

The man who came so close on that occasion to achieving the highest office of trust, responsibility and power in the gift of his countrymen, was our distinguished guest of this evening, the Honourable Richard M. Nixon.

Mr. Nixon was born in what is now the most populous state in the Union, California, but his Irish and Quaker ancestors were long established in Pennsylvania and Ohio. In California he practised for five years after graduating from Whittier College and Duke Law School. And it was from California that he went to Washington as a Congressman from 1946 to 1950 and as a Senator from 1950 to 1952.

His abilities were so swiftly recognized that less than six years after his first election he became General Eisenhower’s running-mate and for the ensuing eight years he was the 36th Vice-President of the United States.

His terms of office were distinctive and historic. The constitution of his country is somewhat less than precise about the Vice-Presidency. Partly by force of circumstance and even more by virtue of his own capacity, Mr. Nixon moved from a traditionally passive or ornamental role into one of active participation in decision-making, not only as the President’s understudy during three periods of serious illness, but as a policy-maker within the inner circles of the administration. At Washington, these were and are awesome responsibilities, the like of which have never before been known.

It would be an understatement to say that Mr. Nixon is a much-travelled man. During the war years he served with the Navy in the South Pacific, attaining the rank of Lieutenant-Commander. As a Congressman he familiarized himself with war-torn Western Europe. As VicePresident he visited 56 countries on five continents. As presidential candidate in 1960 he campaigned in every state of the Union, the first time it had ever been done. In the last three years he has seen at least 20 different countries, on many visits to Europe, the Soviet Union, the Middle East and the Far East.

As I am sure Mr. Nixon knows, this country deeply treasures our British and French heritage, our membership in the Commonwealth, our long-standing friendship with

the United States and our own right of self-determination. The friendship is such that our disputes of the last century are remembered more in jest than in recrimination. In 1813 American forces landed here, less than a mile from this spot, burned old Fort York and the Parliament Buildings, which some would think a highly appropriate choice, and sacked the town, such as it was, but Mr. Nixon has seen the growing city around us today and he will agree that we have almost fully recovered from that invasion. We believe the damage inflicted on Washington and the White House in reprisal has been repaired by now, and all is forgiven.

It is natural that the relationship should be an intimate one, for most of us here have Americans as colleagues, friends and relatives. In matters of trade they are our best customers and we are theirs. Of course it has not been possible, and it was not to be expected, that we would always share identically the same view of world affairs. Indeed in 1914 and again in 1939, we set out on very different paths. However, it shall never be forgotten how much the present and all future generations owe, not only to Britain and the Commonwealth for what happened in 1940 and 1941, but also to the U.S.A. for its mighty contribution and its decisive leadership in the defeat of German tyranny in Europe and Japanese tyranny in Asia, and its leadership in the difficult years which followed. Our guest, as a leading Congressman, was in the forefront of those who made possible the Marshall Plan and the salvation of Western Europe. Like the late Wendell Wilkie, he was quick to recognize the importance of the world to America and of America to the world.

Gentlemen, I now present to you the Honourable Richard M. Nixon.

MR. NIXON:

Mr. President, Colonel Drew, distinguished guests, after that very gracious and generous introduction and your warm reception, I can only conclude that I ran for president of the wrong organization. Your President has correctly pointed out that, as VicePresident of the United States, I visited 56 countries around the world. In all of those official visits, I never had the opportunity to visit Canada. Now, there is a reason for that, a reason which is a compliment to this country. President Eisenhower only sent me to places where we had troubles. So I am here now.

I must say so far my reception has been very warm and I am doubly grateful. I haven’t argued with anybody in the kitchen, I haven’t been stoned. Although I have been informed that if I accepted some of that Newfoundland “Screech” I would be stoned.

On an occasion like this, the speaker from the United States has a formula which is sure-fire for an audience. Inevitably, almost invariably the speaker ends up with a speech that goes somewhat like this.

A discussion of those great traditions we have in common: the common law, the English language, the representative system of government. A discussion of those great conflicts in which we have been comrades in arms, World War I, World War II. A reference always to the greatest, longest border in all the world which is not guarded by either side. These are some of the sure-fire things that can be said when an American is speaking in Canada or a Canadian speaking in the United States.

I am going to depart from that formula tonight, not because it isn’t more pleasant to refer to those things on which we agree; but because this is a special kind of organization with a very special name, The Empire Club. Now, I understand that many organizations that were formerly called Empire Clubs have changed their names in recent years. This one hasn’t. To me that is significant and appropriate. It also gives me the opportunity to discuss a subject which I think will be of more interest to you, while somewhat more controversial. When we think in modern terms, “Empire” does not refer to what happened two centuries, one century ago. It refers, in my view, to a world outlook by those who are its members.

I know that an audience in Canada has interests in the Pacific and in the European area, as well as the United States, I know that this organization and its mem bers are vitally interested in more not than just the bilateral problems that sometimes may divide us. An organization like this thinks of the world. I am sure it also thinks of the role that this country and the United States will play in the world in the last third of the 20th century.

When I mention Canada and the United States in juxtaposition, I am sure that some of you will say, “How can you really put a country of 20 million in the same context as one with 200 million?” The answer is, of course, that while our populations are very different, while our gross national product may be different, while our interests are not always the same, we are parallel on the great issues. We should have in mind that there are no two countries in the world today which, as far as the Pacific area is concerned, as far as Asia is concerned, have a greater interest in what happens there. Also, no two countries outside of Asia that can have a greater influence on what happens there.

This has happened because of the withdrawal of Europe from Asia, especially because of the withdrawal of Britain from Asia. This is true too because the United States and Canada look beyond the present troubles which seem to obscure the larger picture and we can see the great promise of what could happen if Asia could develop its potential and what that would mean to Canada and the United States.

I would like to discuss Asia today in terms not only of the present, but in terms of the promises of the future. In order to report objectively and honestly I must begin with an issue of some controversy: Vietnam.

As one who is vitally interested in America’s relationships with its allies and friends around the world, I would have the very strongest motivation to remove an irritant. It is an irritant in the United States relationship with Britain and France and the other countries in the great alliance. It is an irritant too in the relationship between the United States and some of its friends to the south in Latin America and an irritant too with some of its friends in Canada. Finally as a politician and as one who is sometimes a partisan, I would naturally like to find an issue on which I can be, not only partisan, but also speak for the best interests of my country at the same time and therefore be against what the national administration is doing.

I want to tell you why I, as a member of the loyal opposition, I believe that the commitment that the United States has made to stop conquest by export of revolution in Vietnam is one that had to be made, one that must be carried through to a successful conclusion and one that, when it is concluded, will open an entirely new era for peace, for freedom and for progress in Asia. That is my conclusion.

Let me give you the reasons for it and at the outset let me, of course, say that many people with as large and more background than I have in foreign affairs have reached a different conclusion. They could be right. But based on my travels of that area, based on my analysis of foreign policy, not only in the present but in the years past, I believe that some of these conclusions that I now will report to you are worth considering.

Looking at this war in Vietnam, let me present it first in terms of how it began. I do this not because this sophisticated audience is not aware of it but because in country after country I had statesmen ask questions about Vietnam which proceeded on the assumption that the United States was the aggressor in Vietnam. Let us begin with one fact and that is that the war in Vietnam began and the United States participation in it became necessary because North Vietnam sent logistical support, men, materials, into South Vietnam for the purpose of inspiring and supporting a revolution designed to take over South Vietnam and bring it under the domination of North Vietnam.

Had the North Vietnamese intervention not occurred the support of the United States of America would not have been necessary in my view. It could have been handled by the South Vietnamese themselves, weak as they were at that time. But once North Vietnam moved in the United States at the request of South Vietnam sent men, money and materials to South Vietnam.

Here let us understand one point as to what the American objective is not. Our purpose there is not to conquer North Vietnam. Our purpose is not to punish North Vietnam. The United States is assisting South Vietnam in its attempt to retain the right to choose the kind of government it wants. Once that right is assured, once the aggression subsides to a level that the South Vietnamese can contain, then the American commitment can be withdrawn.

We hear so often of the risks of winning the war over aggression in Vietnam. It is said that if the United States persisted in attempting to assist South Vietnam to win the war over aggression in the south that there was a great risk of starting World War III.

I would put the proposition another way. I think the risk of winning in South Vietnam is infinitely less than the risk of losing. If the United States had not come to the assistance of South Vietnam, or if, the United States either at the conference table or by precipitate withdrawal allows North Vietnam to gain its objective in whole or in part, the result would be catastrophic, not only for South Vietnam but for the balance of nonCommunist Asia as well.

Let me go back a little in history. I remember when the Korean war began in 1950, I was in the Senate at the time and I recall talking to one of our top experts on Communism in the American Government. I asked him what he thought about the American commitment as far as Korea was concerned and the United Nations commitment in which, of course, Canada also participated. His answer was extremely perceptive, both as it applied to Korea and as it applies to Vietnam. He said, of course we have to help Korea. He said, what you must realize is that to the Communists the war in Korea is not about Korea, it is about Japan. Looking back I can see why. Japan was weak at that time. Had Korea fallen, Japan would then have been pulled inevitably towards the Communist order. But by keeping the cork in the bottle in Korea, Japan was able to develop the necessary economic and political strength which now makes it one of the strongest bastions of freedom in Asia, and so it is with Vietnam.

The war in Vietnam is not just about Vietnam, it is about all of Southeast Asia. While I know that many consider it not fashionable to talk about the domino theory these days, make no mistake about it, anyone who has been to Asia as many times as I have in the last five years and talked to the leaders of these governments will know that they are extremely conscious of what the wave of the future may or may not be. Once they believe that the wave of the future inevitably is that the main power of the Communists or even the Chinese Communists is inevitably going to sweep over the balance of Asia, they will adjust to that inevitable fact. But once they are convinced that it is not inevitable, then a whole different course of action will take place.

Looking again at Vietnam, in my view it is the cork in the bottle. We are there for the purpose of seeing that the people of South Vietnam do have the chance to choose their own form of government. In my view 75% to 80% of them would vote today against a Communist government if they had the opportunity. On the other hand we must remember that in the event that they are unable to hold the line with our assistance, one after another those nations of Southeast Asia would come under the pressure which I think would be inevitable. So what we are talking about is not just Vietnam, we are talking about Southeast Asia, we are talking about the Pacific and with all these great factors on the line, you can see why the United States, despite all the difficulties of this war, despite all of the tragedy of it, despite all the unpopularity of it at home and abroad, has made the commitment that it has made. I think history will record that this is one of the great turning points in what happened in Asia.

Now, let me look forward a moment. I know many of this audience would like an appraisal as to what will happen, how long will the war last and, of course, no one can predict this.

I can give you certainly some indications of what conditions must be met before the war in Vietnam does come to a conclusion. First the leaders of North Vietnam must be convinced that they cannot win the war militarily. Second, they must become convinced that they cannot win the war politically in the United States. Third, they must become convinced that they are not going to get a better offer of settlement by hanging on.

On the first point, they are convinced that the overwhelming superiority of the United States and Vietnam and Korea and other forces in Vietnam is such that the leaders in North Vietnam know they cannot win the war. On the second point, they are not convinced. They misinterpret the American political system with all of its vigorous debate. They assume that if they hang on perhaps through the elections of 1968, that the United States will find a way to settle the war which will give them at least part of the package for which they began the war. Third, every time the United States changes its offer of settlement publicly, every time it departs from a firm line, inevitably it gives some encouragement to the men in Hanoi who are taking such punishment militarily. But looking at the situation, I am convinced that the war will be brought to a successful conclusion, that the United States will have the will and the determination to see it through.

There has been a great deal of conjecture about whether or not the Chinese Communists would enter the war. No one can be sure. I would point out, however, that those who draw the parallel between Korea and Vietnam overlook a historical fact.

At the time of Korea, Communist China and the Soviet Union were allies and Communist China had the logistical support and moral support of the Soviet Union in its intervention in Korea. Now, the Soviet Union and Communist China are not allies.

What does that mean on this very simple point? The Communist Chinese lack the power, even though they may have the desire, to intervene in Vietnam. This does not mean that the United States should or will provoke them more than it has, but it does mean that when we talk loosely about the danger of doing what is necessary to stop oppression in Vietnam, we should not over-estimate the risk of what Communist China may do.

Let us assume that the war does reach a successful conclusion. Let us assume then that we look forward to the next ten years. What will happen and what is going to happen in Asia after Vietnam? And here it is pleasant to bring what I think is good news; news that has been obscured by the day to day battle reports, by the fears that something may happen in the event that this does escalate more than was expected.

Today the picture has changed 180 degrees in nonCommunist Asia from what it was when I was there first in 1953 on a round the world trip at the direction ~of President Eisenhower.

On that trip I visited all of the countries of Asia except, of course, Communist China. I talked to all the leaders and in 1953, in Japan, in Thailand, in Malaysia, in country after country on the perimeter of the Communist heartland. The leaders of those countries weren’t sure on two points.

First, they weren’t sure whether the Communist system in one form or another might not be a better system for their society and second, they weren’t sure as to whether Communism or freedom would be the wave of the future of the nation. Fourteen years have passed. The same trip I took in August and then again two months ago to the same capitals where I talked to some of the same leaders and many new ones. The word today is this: One great victory has already been won in Asia. The Communists have lost the ideological battle. What is being decided in Vietnam very simply is this: whether Communism will be able to accomplish by force and terror what they are unable to accomplish by persuasion. In all of these nations there is no question, if they have the opportunity to choose and the right to choose, they are not going to choose the Communist way.

There are several reasons why this is so. The failure of the Communist society in China, its failure in North Vietnam, its failure in North Korea. But even more im portant is the striking, spectacular success of non-Communist societies in the non-Communist countries of Asia. Let me take you around the perimeter very briefly. Japan is not the kind of free society that we know, but it is a miracle of production and is a strong bastion of freedom. Korea has the highest growth rate now in all of Asia. Hong Kong is having difficulties because of its immense success. Thailand is the country that all said couldn’t make it. Today it has the second highest per capita income in Asia-next to Japan and one of the few nations in the world, incidentally, that has worked its way out of foreign aid. Malaysia and Singapore are unhappy in a way because of the present division between Malaya and Singapore, but both are examples of boom societies under their concepts of freedom, somewhat different from ours. Singapore is more a mixed society leaning towards socialism, Malaysia flows a little in the other direction, but both are successful.

Let me turn to two others. Indonesia has 100 million people. As you know, Indonesia was on the razor’s edge, of being taken over by the biggest Communist party in the world, outside of the Soviet Union and Communist China. It would have been taken over unless the cork ifi the bottle had stayed in in Vietnam. The Indonesians, in my view, would not have dealt with the Communist Chinese conspiracy unless they had felt that there was hope that they could survive.

Indonesia, let me say parenthetically, is a striking and tragic example of one of the great lessons of history: Those who lead revolutions seldom are the men who can lead during the period of reconstruction. Sukarno was a great revolutionary agent but revolutionary leaders are destroyers of institutions.

India has terribly difficult problems. Two wars in the last five years; the Communist Chinese invasion and the war with Pakistan. Add to that an over-populated country, add to that an economic system that is not attractive to private capital, the future of India, in my view, is still in the balance.

On the other hand India has fought for freedom. It has a parliamentary system and the common law. I believe that India itself as well as Pakistan will be able, at this critical junction, to move forward with the balance of Asia.

Let us look now at what might happen after Vietnam and here there is an exciting new development. What has developed in Asia is a new sense of community, a new sense of participation by the Asian countries along with Australia and New Zealand who are now accepted as Asian countries. This is the most exciting new development in international affairs, in my opinion, in the world today. The Prime Minister of Singapore put the reason most eloquently when he said, look at the population of these countries. In Canada you will understand this because half of your population is less than 21 years of age. He said, that World War II is far behind and we have a young population and a young people in Asia who have neither the old hates or the old guilts. That is why leaders in Singapore and in Manila and in India are now talking to those in Japan. That is why Japan is now able and will be able to play an increasingly significant role in the economic and political development of a United Free Asian community.

Now, let us come to the most difficult problem of all–the future of Communist China. Some say, “Why do we continue to isolate China?” “Why do we isolate China by refusing to recognize China?” It is said that if only we woulld recognize Communist China and admit it to the United Nations, then Communist China would change just as the Soviet Union has changed. We would have a reduction of tension and eventually the communication, the trade and everything else that means peace for the future.

Let me say if that was all it would take, I think all of us would support the proposition, but let us look a little further. Why has the Soviet Union changed? Not be cause it was in the United Nations, not because it was communicating with the United States and with other powers in western Europe. The Soviet Union has changed not because of a change of the heart, but because of a change of the head.

The change began with the break with Communist China. The Soviet leaders then determined that it was to their interest not to have enemies on two fronts. The change also came as western Europe developed an economic stability of such massive strength that pushing outward in that direction was no longer profitable. The Soviet Union changed, you must not forget, at the time that their leaders looked down the gun barrel in Cuba.

I do not mean that the change is not real. It is real. But I do mean the change came about once the Soviet leaders became convinced that a course of aggression was dangerous and that a course of conciliation was more in their interests.

On the other side of the coin, the Soviet Union is attacking the Indian Government more vigorously than ever before. It is doing the same thing to the Government of Iran. There is no question that the Soviet Union is fishing in the troubled waters of the Near East.

What I am suggesting is that the Communist powers have not changed their ultimate objective of conquest without war, if possible. We must also have in mind that they will change, however, when necessity requires it. That brings us back to the problem of China.

In my view, if the principle is established that conquest by exploit and revolution will no longer be tolerated, it will have a dramatic effect on the hard-liners in Peking. Just as these previous matters to which I referred, had had a dramatic effect on the hard-liners in the Soviet Union. When you combine that lesson with a strong, free Asian community of 300 million people and a production three times as great as that of Communist China, then the Communist China leaders will have reason to build their bridge as we will build our own.

I would like to leave this thought to the members of The Empire Club. There are scholars in the United States, who constantly parrot the theme that the interests of the United States and Canada, because of our traditions, are primarily in Europe and the Americas. These are our people, and share our traditions. The argument goes that in Asia people have different traditions and a different background, and a different colour. This, therefore, is one of those peripheral areas from which the United States, and other nations for that matter, could well remove their interests.

Any man who thinks of Empire, thinks not in terms of conquest but in terms of the idea of a whole world rather than a half world. Any man who thinks of Empire must reject this kind of philosophy because the world is getting closer and closer together.

The people of the Pacific area do not want to come under Communist domination and we have to assist them if they desire to avoid that eventuality. For our own vital self-interest we will help to build in this last third of the century a world in the Pacific which will be a better world for them and an infinitely better world for us, economically, politically and militarily.

Over a century ago at the historical Guildhall in London a great dinner was held celebrating Nelson’s magnificent victory at Trafalgar. A toast was proposed at that dinner and a response made. That response has been evaluated by those who are experts of English eloquence as one of the three greatest speeches in the history of the English language.

The toast was to Pitt, the Prime Minister and he was hailed as the saviour of Europe. He rose and responded in three sentences. “I thank you for those generous words.” He said, “But Europe will not be saved by any single man. England has saved herself by her exertions and will, I trust, save Europe by her example.”

Today, if I may paraphrase, Canada and the United States in this last third of the century will save ourselves by the power of our hearts and by the power of our ideas. By our example we will save a cause that is bigger than our differences: the survival of freedom in the Pacific and the world.

by E. A. Royce.

Thanks of the meeting were expressed